SAN FRANCISCO—Josh Wardle, creator of the game Wordle, arguably holds a world record for the fastest sale of a massive new game the instant it became a worldwide phenomenon.

Hence, his presentation at the 2022 Game Developers Conference has a different flair than the usual "post-mortem" dissection of a finished game. His presentation has plenty to dissect, including the "low seven figures" deal that saw him sell the whole thing to The New York Times at the end of January. But in addition to questions about how Wordle was born, Wardle seems aware of the unspoken question on everyone's mind: Why would you move on just as the game took off?

Answering both of those questions, to some extent, requires appreciating that the Times had been in Wardle's mind well before Wordle joined its family.

“The best co-op gaming experiences”

"The New York Times, in the end, was actually a really good buyer for the game," Wardle says while standing at a GDC podium in modest dress: gray shirt, blue jeans, slightly receding hair pushed back with thick glasses covering his expressive face. "I think they'll be great stewards. Their games play an important part in the origin of Wordle. They treat their players with respect. I don't think they're going to cover the game in ads or anything."

Exactly how the Times handles Wordle from here on out, however, is not Wardle's concern—a fact he emphasizes in this talk, when he expresses his relief to finally be free of the "stress" that Wordle added to his life. Before he parted ways with Wordle, there was the matter of building it.

"I think crosswords are one of the best co-op gaming experiences," Wardle tells the crowd, and in his case, this means the daily, meditative play he and his partner shared at the beginning of 2021, pens primed over the New York Times' crosswords in particular. "There's something about looking at a clue and someone else looking at the same clue but arriving at a different solution that's kind of beautiful. It teaches you something about the other person."

Wardle warns the crowd that he'll be getting "a bit MFA, arts degree" as he points to a quote from literary theorist Terry Eagleton: "Language is the very air I breathe." Wardle then pleads with the conference's crowd of game devs to think about making more games with words rather than fearing backlash for making stuff that resembles Words With Friends: "If you make words a core mechanic of your game, everyone comes to your game having a deep understanding of its fundamentals. You don't have to teach them about words."

Wordle’s mastermind talks about Mastermind

After explaining exactly how Wordle works (players get six guesses to figure out a five-letter word), Wardle cops to a comparison that many avid gamers (including commenters on Ars' first Wordle article) have made about his eventual hit game: the 1980s board game Mastermind.

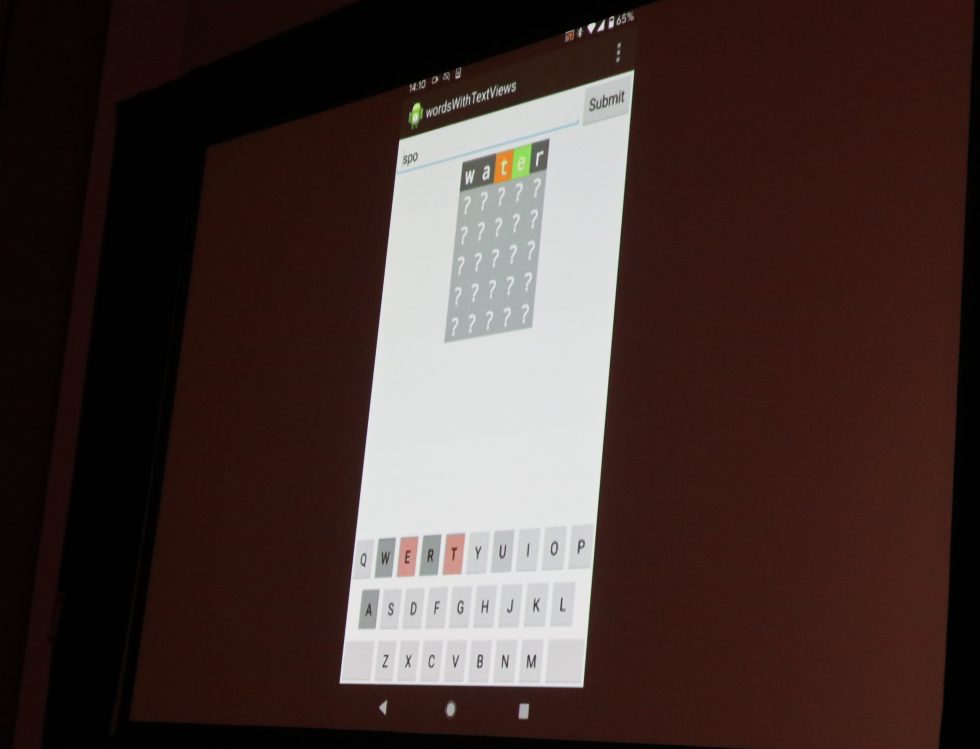

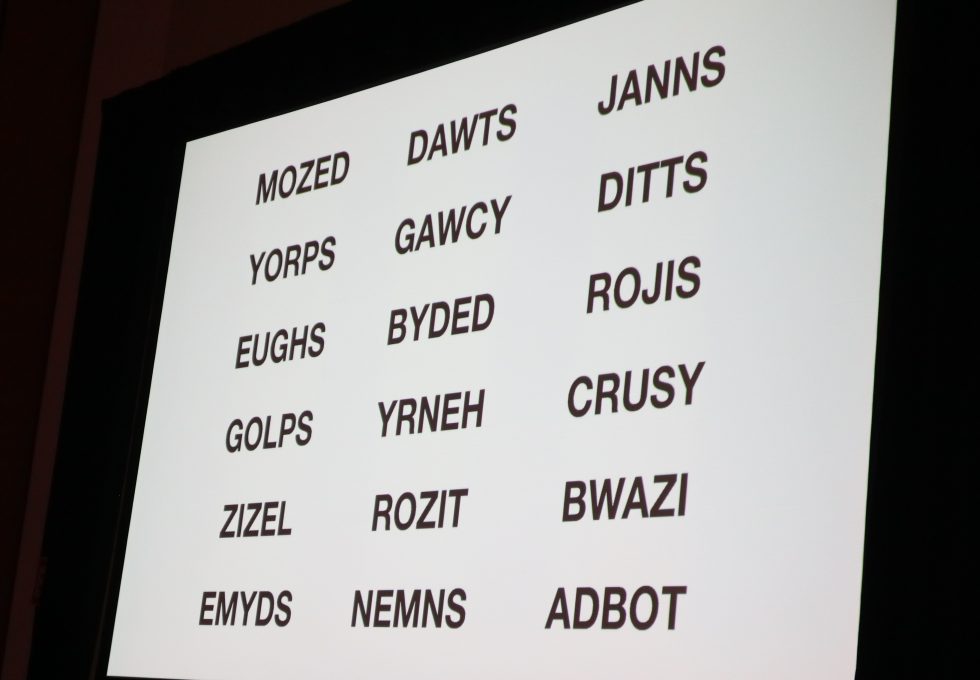

When building Wordle's first prototype in 2013, Wardle thought back to the "guess the color" system of the aforementioned board game. "What if you were guessing words instead of colored sequences?" he asks the crowd. The final game's five-letter concept stuck at that long-ago point, but Wardle realized something wasn't right when he dumped a massive list of every possible five-letter word into the app's random-word pool:

"It turns out that these are all valid five-letter words," Wardle says while displaying the above image, drawing a laugh from the crowd. After testing the worst outliers in his game, he had a revelation: When players encounter a word they've never heard of or used in common speech, they are left with little rational means of guessing what the next letter might be, even as grays, greens, and yellows accumulate. Early players couldn't ascertain how those letters might connect to each other (i.e., trying common consonant and vowel combinations). The result was identical to Mastermind, where the color draw is random. Wardle didn't want that.

"What's fun about Wordle, I think, is what you can tease out, based on what you know about language," Wardle says. "What the word should be."

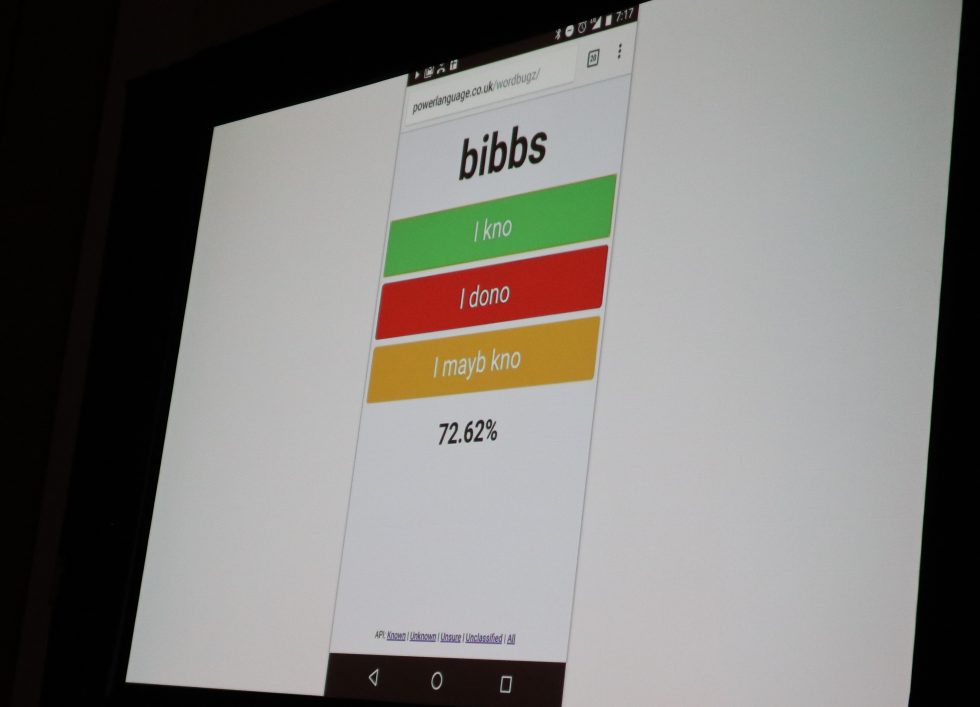

The design solution came thanks to Wardle's partner "going through a tough time" and wanting a "mindless game to play." So he turned her into a human machine-learning model by having her rank every single five-letter word in the dictionary—roughly 13,000 of them—with the following ranking system:

“Something, frankly, that I wasn’t intentional about”

This sorting, which eventually defined Wordle's "five years"' worth of words, was completed in 2014, and it was followed by Wardle "kind of losing interest in the game." He got caught up in web development and design work, including the likes of Reddit's explosive, limited-time experiment Place. Years went by. A pandemic took hold. Wardle and his partner were still together, and in lockdown, they began enjoying the NYT's crossword on a daily basis.

One byproduct of this shared gameplay was that it made Wardle aware of the NYT's digital slate of games, including Spelling Bee. He then remembered Wordle as a long-ago experiment, and he was inspired by two things that he found approachable and novel about Spelling Bee: It existed as an easily accessible website, which made it incredibly easy to share, and it forced players to a limit of one puzzle a day.

"[Only one puzzle a day] is something that you're not meant to do, especially with mobile games, right?" he tells the crowd. "There's this expectation that you give the person what they want: to play endlessly. As soon as they're done, move on to the next one and the next one. I didn't want that. What if a game was just three minutes of your time a day? And that's all I want from you?"

He needed hindsight to recognize the "social aspect" that his once-a-day structure enabled. "That ended up being a huge part of the game and something, frankly, that I wasn't intentional about," Wardle says. "Maybe there was an intuitive understanding that that would happen."

And his decision to make Wordle a website instead of an app came largely because he shifted to web development in his full-time job. This meant his game couldn't deliver things like push notifications or "capture" gameplay attention, which he "wasn't interested in."

“A club that you’re either a part of, or not”

The game hid in plain sight on the Internet starting in January 2021, but as previous Wordle profiles have clarified, its expansion kicked off when it moved beyond being a game that Wardle and his partner played by themselves. The introduction to the outside world came when Wardle sent the game to his in-laws, who quickly embraced the game as part of their family's WhatsApp group chat. His family members became so enamored that they had to create a second group chat dedicated entirely to Wordle since the game had become so "disruptive."

Wordle's steps to mainstream success went from there. Wardle shared the game with a few more close friends. It moved virally from there, eventually landing as a "footnote" in a New York Times newsletter (there are those three words again). Soon after, Wardle looked at the site's traffic and saw an explosion of user activity in... New Zealand. Wardle still isn't sure why, but the game absolutely exploded on a per capita basis at that time.

One New Zealand player began sharing Wordle results as hand-crafted emoji grids of gray, yellow, and green squares—which, Wardle noticed, cleverly told a Wordle solution's story without spoiling its solution. (Maybe someone was haunted one day by five yellow-filled guesses, or maybe someone else had a ridiculous two-guess solution.) This inspired Wardle to build an automatic emoji generation system so more players could easily share their emoji grids, which helped the game go viral.

As I wrote in January:

An outburst of green, yellow, and gray squares on friends' daily feeds got what little attention I could spare [during an omicron infection]. What were these patterns? Why were fewer rows of boxes apparently better? And how come my favorite smart people were obsessed with it?

Wardle points out that he received instant blowback from game developers who tracked Wordle's success: Why wasn't there any URL or Twitter handle linking to the game in this auto-generated template?

Wardle, again, shrugs his shoulders at anything beyond simple, elegant fun, telling his GDC crowd: "With a link, it looks kind of crap, in my opinion. And if the game has an agenda to get you to share, like, why? Because they want to do it? Or because it's good for the game? Removing the URL felt simpler." (He then acknowledges that its "cryptic" emergence as emoji bubbles on Twitter turned it into "a club that you're either a part of or not.")

I’m sorry, how many Wordle grids at once?!

This is when Wordle got big. How big? Wardle points to the GDC projector screen, which displays a Beatle tweeting about Wordle. Then he quips, "That's Paul McCartney, probably cheating at Wordle" with a one-line solution. (As it turns out, McCartney was using Wordle's structure to slyly suggest a festival concert date on "25/6," or June 25, while using Wordle's "X/6" Twitter parlance.)

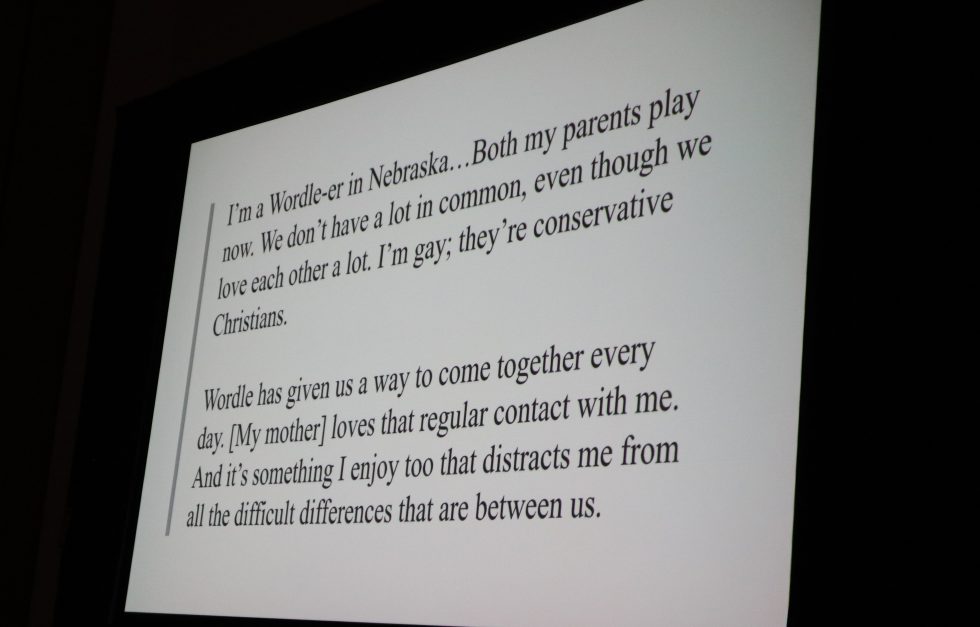

Wardle's rapid-fire summary of Wordle's explosion includes talk show mentions, a profile by Monica Lewinsky, a person who cross-stitches every single Wordle solution, a letter from a fan thanking Wardle for the game bringing a distant family together, a TikTok showing how a classroom playing the game as a group invigorated their love of words, and a newspaper profile from the small town in Wales he grew up in, which featured the headline, "Farmer's son's Wordle saves hostage gram."

Perhaps above all that was, yes, an in-depth New York Times feature from early January. The paper focused on the story of Wardle creating Wordle as a gift for his partner. "It made us both feel quite uncomfortable as private people, but it was a good story, right? She really enjoyed [Wordle], but so did a bunch of other people."

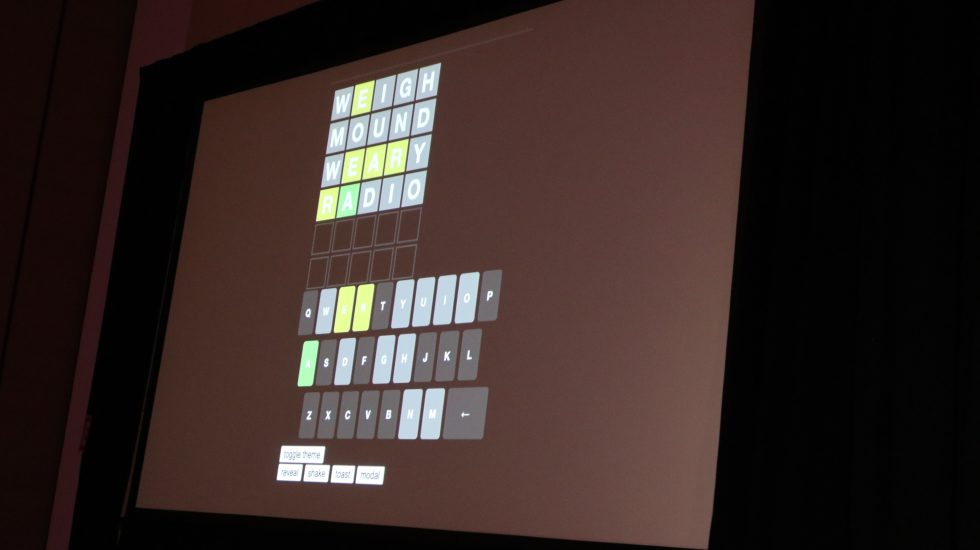

Wardle giddily lists other games that ran with the Wordle concept and added their own tweaks, from Heardle (Wordle, only with sounds) to Worldle (a name-that-country guessing game) to Kilordle (an overkill smorgasbord that makes players deal with 1,000 Wordle grids at once).

And if you're wondering about the game's technical aspects: Wordle's inherent simplicity was a boon for its eventual explosion in traffic. "The game was all client-side, JavaScript, 63KB total," Wardle says. "I put a CDN in front of it. Ninety-nine percent of my traffic got served by the CDN. I was paying an estimate of $100 a month. That was only possible because I made the game really, stupid simple. Part of that was because I was an idiot. But also, there was no API. I wasn't querying to validate or fetch words."

The breaking point: “It was all going to get really, really complicated”

But there was also the matter of copycat games that weren't run so innocently.

"I was making a game for my partner," Wardle explains. "I'm not going to put ads on it. Even when it became really popular, I felt, why can't there be a nice thing on the Internet that people can play? But other people were totally fine monetizing the game."

Wardle noticed copycats with different names (or even the same name) either emerging with ads or being sold on smartphone marketplaces. "It felt really complicated to me, really unpleasant, in a way that I don't quite know how to feel now. People over here are making money from the game. That isn't money that I would have made. But something about that felt deeply unpleasant."

Wardle's voice is as quick and rapid-fire when he goes from describing the ways Wordle connects people and families, to talking about the game's dark side. His face tightens, and he stumbles over his words.

"I don't want to be paying a lawyer to issue cease-and-desists on a game that I'm not making money from. It felt like it was all going to get really, really, complicated in a way that, just, I, uh, you know, pretty stressed out, truthfully."

though Wardle didn't clarify exactly how the deal took shape or was arranged, he is blunt: "Selling to the New York Times was a way for me to walk away from all that." He points squarely to his interests as an "artist" as a major reason he's at peace without Wordle in his life anymore.

He says other game developers would almost certainly handle Wordle's exponential growth differently.

His version of events, at least, ended in "probably the best possible outcome that there could be." Wardle admits during a Q&A session that "what-ifs" come to mind on occasion. He says he contends with hints of regret by "reminding myself how I felt around that time. And I felt mis-er-a-ble. I attribute that misery partly because I felt an enormous amount of pressure, because I had a spotlight on me. But I felt like I had limited time. All these people were trying to copy the game."

Instead, Wardle is happy to say that he doesn't have a concrete plan for what's next in his life. "I'm just gonna bugger around and see."

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.