There seems to be much less excitement about distributed computing these days.

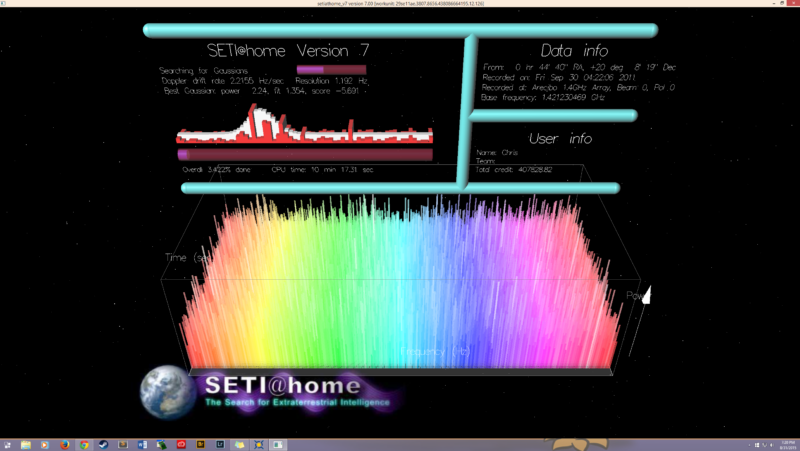

Distributed computing erupted onto the scene in 1999 with the release of SETI@home, a nifty program and screensaver (back when people still used those) that sifted through radio telescope signals for signs of alien life.

The concept of distributed computing is simple enough: You take a very large project, slice it up into pieces, and send out individual pieces to PCs for processing. There is no inter-PC connection or communication; it’s all done through a central server. Each piece of the project is independent of the others; a distributed computing project wouldn't work if a process needed the results of a prior process to continue. SETI@home was a prime candidate for distributed computing: Each individual work unit was a unique moment in time and space as seen by a radio telescope.

Twenty-one years later, SETI@home shut down, having found nothing. An incalculable amount of PC cycles and electricity wasted for nothing. We have no way of knowing all the reasons people quit (feel free to tell us in the comments section), but having nothing to show for it is a pretty good reason.

Rises and falls

SETI@home’s history is emblematic of the churn that typifies the distributed computing world. Another major effort came from IBM; its Corporate Social Responsibility division was involved with the creation of the World Community Grid, a series of life science projects searching for treatments for AIDS, cancer, and Alzheimer’s. IBM donated its technology and talent to the project, which kicked off in 2004. But in 2021, IBM transferred the World Community Grid assets to Krembil Research Institute, part of the University Health Network (UHN) of Toronto. A UHN spokesperson declined to comment for this story.

With the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, there was a new darling in the distributed world: Folding@home, a simulator trying to understand how proteins adopt functional structures. Folding@home had been around for more than 20 years simulating protein folding to understand how diseases were formed. And it had something to show for this work: more than 230 peer-reviewed papers on its findings over the decades. But, with proteins from SARS-CoV-2 to study, Folding@home became the It Project. So many people launched it on their computers that it broke the exaFLOP barrier long before supercomputers did.

But as the pandemic waned, so did interest in the project. Greg Bowman, the director of Folding@home and a professor of biochemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, said the project skyrocketed from 10,000 active users to 1 million but quickly dropped to around 45,000 active users—which is still quite a gain over the pre-pandemic numbers.

Bowman thinks there is a combination of reasons for interest dropping off. “The pandemic gave huge motivation and a lot of time for new hobbies. Lots of organizations had idle computers they redirected to Folding@home. One example: FIFA didn’t have any need to scan YouTube for pirated content since no games were happening.” It didn’t last, though. “Inflation and energy prices soared,” Bowman said.

Even DistributedComputing.info, an aggregator of distributed projects, had gone a few years without an update before its January 2023 update. But the site's operator, Kirk Pearson, says he hasn't abandoned the project; he’s just been busy with real-life matters.

Direct involvement

Pearson suggested that the center of attention has shifted to projects that more directly involve users, primarily at a site called Zooniverse. “I agree there have been fewer large-scale new distributed computing projects starting in the last few years, but look at all of the new projects that have begun at Zooniverse in the last few years to see how much innovation and creativity is going on in distributed computing and in distributed human-powered projects,” he said.

Pearson said Zooniverse is for "distributed human" projects, where humans do the work for the project that computers can't, like identifying the numbers and types of animals in a photograph. Because Zooniverse has a relatively simple framework, it is easy and inexpensive for someone to create a new Zooniverse project. That has led to the current proliferation and range of projects within Zooniverse.

“It is possible that volunteers are moving to Zooniverse projects because they want more involvement in projects, but I don't think there is enough evidence to support that claim. I think volunteers are drawn to new projects.” He suspected that “if you could follow trends in levels of participation in Zooniverse projects, you would see that the majority of volunteers move from existing projects to new projects due to the novelty of the new projects.”

Other people have ascribed the decline to additional factors. David Anderson is a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, former director of the SETI@home project, and current director of the BOINC distributed computing project. He wrote a lengthy treatise on the subject in early 2022. He said distributed computing peaked in 2007 and has been on a decline ever since for a number of reasons, from a lack of mass appeal to a lack of volunteers and a strong leader to no presence on social media. He declined to comment further.

Practical issues

The rise in power costs is another big contributor to the decline in distributed computing. Altruism will only get you so far when your well-meaning hobby is causing the electric bill to spike. Electricity bills are generally increasing, and the new generation of desktop CPUs and GPUs are incredibly power-hungry. Making matters worse, fewer people have this hardware due to the general shift from desktop computers to laptops. Running a CPU at full utilization will drain even the most efficient batteries. “Things have dropped sharply as people get hit with energy prices and inflation,” said Bowman. “I think there's lots of interest, but energy prices and other economic factors have hurt participation.”

Then there is the fact that they have nothing to show for it. Many SETI@home users likely felt that they had burned through all that electricity for nothing. In other cases, the project’s scientific research and individual findings haven’t really stood out—it has gone into a collective pot of findings that might be discussed as part of a research paper. And the users themselves might not even know about it.

Then there is the lack of a strong, charismatic leader, as mentioned by Anderson. How do you get people energized and excited over leaving a computer running to possibly find a scientific nugget? It’s a hard sell, and in the absence of a charismatic leader, no one is selling it.

Finally, the projects are often boring. What initially made people enthusiastic about running Folding@home was the potential to find a cure for COVID. With SETI@home, it was the potential to find signals from another world. But how sexy is something like Einstein@home, which looks for neutron stars? Changing the world is an easier sell.

While it may be past its peak, however, distributed computing hasn’t gone away entirely, and it still attracts enough computing power to be useful. Pearson said that while a few of the more well-known distributed computing projects have ended, most of the less-publicized projects he covers are still going strong. “Distributed computing is not dying any more than chemistry or mathematics are dying,” he said.

Andy Patrizio is a freelance technology journalist based in Orange County, California (not entirely by choice). He prefers building PCs to buying them, has played too many hours of Angry Birds on his iPhone, and collects old coins when he has some to spare.

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.