Andy Bozzo, a fire captain with Contra Costa Fire Protection District, was surrounded by flames as he and his unit battled the Caldor Fire from the small El Dorado County town of Meyers.

“Spot fires were dropping in hourly as we were defending that area,” he said. “We needed to know where our units were, but we had zero cell service, even though this was a neighborhood 10 minutes away from a Raley’s and Safeway, because the cell towers had burned down.”

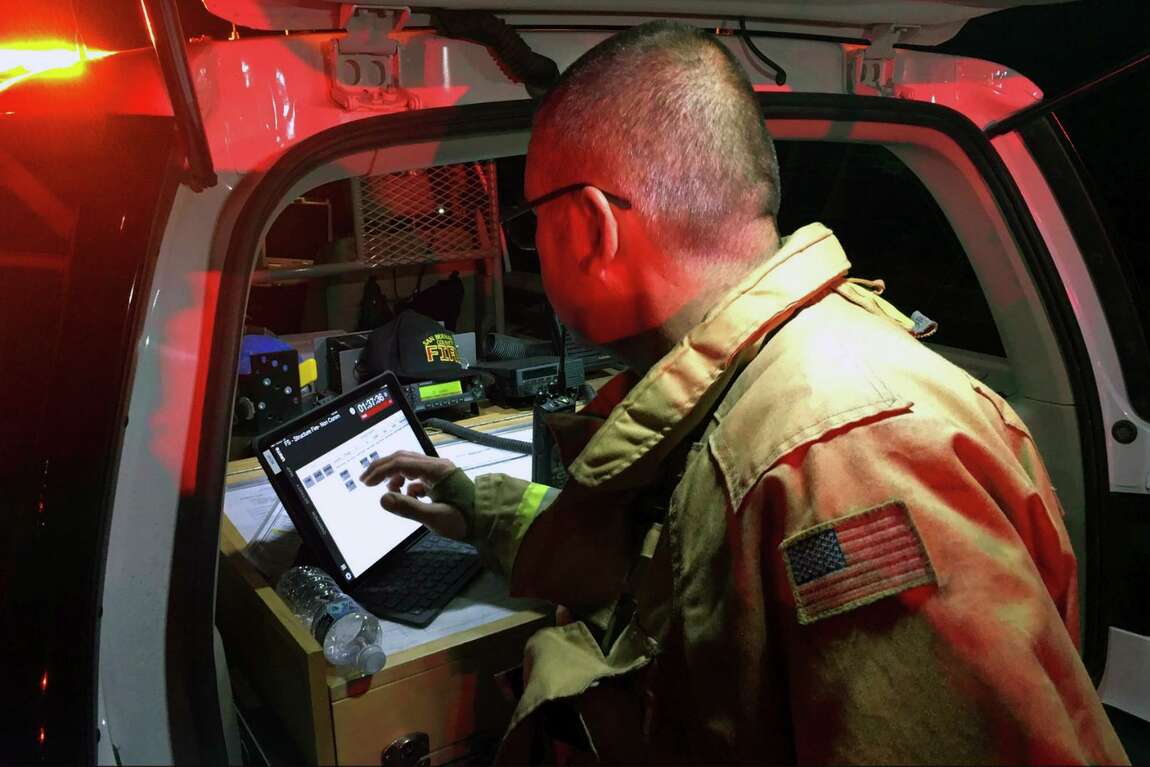

But thanks to iPad software that Bozzo and Will Pigeon, a Contra Costa assistant fire chief, had developed, they were able to see a bird’s-eye view of their engines overlaid on an updated fire incident map.

Tablet Command uses live vehicle GPS tracking to monitor where fire equipment is at all times. In Bozzo’s words, it shows “real-time tactical placement of apparatus referenced against maps showing a fire’s latest progression, along with other data on hot spots and infrared views.”

Or put more informally, it’s like seeing a game of Risk come to life.

Amid the chaos and confusion of a fire, especially a wildfire, it’s hard for firefighting leaders to keep track of where all their trucks and people are.

“When all hell is breaking loose, that creates a communication fog and visualization fog,” Bozzo said. Tablet Command helps “to clear the fog and have a clear view of what you’re approaching. You can see vital information to take action and make decisions.”

The idea came to Bozzo in 2009 while he was playing “Words With Friends” on an iPhone 2 and realized that similar technology could track fire engines’ locations. He reached out to his friend and fellow firefighter Pigeon, who has a computer programming background, and the two launched the company Tablet Command, based in San Rafael.

To date, Tablet Command has raised $2.1 million, modest by Silicon Valley standards. It has annual sales of $1.6 million, projected to grow 60% annually. More than 125 fire departments across the U.S. and Canada use it, including multiple agencies in the counties of San Francisco, Marin, Contra Costa, San Mateo and Sonoma, the company said. CalFire units in San Diego County and San Bernardino County deploy it as well.

Customers generally have an iPad mounted in their fire engine’s shotgun seat where the captain sits, as well as an iPad for battalion chiefs and other leaders. The sofware also runs on a web browser and phones. Pricing comes to about $500 a year per iPad, so a small department might pay about $6,000 a year, while a large agency could have a six-figure annual subscription. Phone licenses are about $10 per user.

Bozzo is still an active-duty firefighter while Pigeon recently retired to devote himself to the company. Their extensive on-the-ground experience means they grok “real-world problems fire captains encounter on a day-to-day basis,” Pigeon said.

Wildfires have changed in recent years, becoming intense, long-lasting and far-reaching conflagrations fueled by extreme drought and climate change, but often the tools to fight them are often decades old. Experts say “situational awareness” — understanding what’s going on around you — is a key weapon for firefighters. That’s where Tablet Command comes in.

“It gets us out the door faster, giving the firefighters a heads up to what we’re going to, giving a visual overview of what that property or area looks like,” Bozzo said. “It enhances our safety: like going into battle and knowing how the enemy is dressed, how they’re armed and positioned ahead of time before engaging.”

The 2018 Carr Fire near Redding spawned its own fire tornado — a terrifying and rare phenomenon in which a vortex of rising and spinning hot gases, smoke and flame reached some 17,000 feet above Earth, traveling at an estimated speed of about 143 mph.

As Pigeon tells it, a Marin County fire engine got separated from a multi-unit strike team, turned around and went down the wrong road just as the tornado started to kick in. As the sky went to almost complete black and visibility dropped, they radioed their battalion chief, saying they didn’t know how they’d get out.

As some of the Marin firefighters tell it on an online video, “We were in an area that was non-survivable.”

“The battalion chief got a lump in his stomach,” Pigeon said. “He opened up Tablet Command and was able to see their location on a (fire) map — and could see there was a safety zone ahead of them (an area where the fire was not burning so they would not have to deploy their fire shelters). He said, ‘Continue on down 1.5 miles down Keswick Dam Road, and you will make it to a parking lot where you will be safe.’ They made it down to the safety zone, a parking lot by a dam, and hiked down to the water.

“If the battalion chief hadn’t been able to recognize where they were and talk them to their safety zone, there could have been a huge difference in the outcome — possibly four funerals.”

Jason Martin, battalion chief for the Menlo Park Fire Department, who had recently returned from fighting the Caldor Fire, said Tablet Command has proved invaluable.

“I can give people assignments based on the incident command tracking system, as well as marking things like a dangerous tree or split in a dirt road and making notes about them,” he said.

When multiple agencies battle a fire — as is the case with all of California’s large wildfires — Tablet Command lets him monitor where other companies are deploying equipment (if they are also using the software).

“I can see every San Mateo County fire unit, even if it’s on the other side of the fire,” Martin said. “It’s an amazing tool and is especially beneficial in wildland fires. It’s been a game changer.”

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.