Op-ed: Slowed manufacturing advancements are upending the way tech progresses.

For many, many years, I wouldn't get a new game console until a couple years after it launched. This was partly because I wanted any new console I bought to have a decent-sized library of things to play, and partly because it sometimes paid to sit back and see which console was going to "win" the generation in terms of first-party exclusives and third-party developer support.

But mostly it was because, from the Atari VCS in the 70s all the way up through the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One generation in the 2010s, you could always count on game consoles getting cheaper as time went on. Those price reductions would often also come with internal tweaks and external redesigns—smaller or slimmer or otherwise improved versions of the console that made them superior to the originals (though you would occasionally lose a lesser-used feature or two along the way).

But both of those things have mostly stopped. The last permanent price drop for a major home or portable console we could find came back in 2016, when the PS4 Slim launched and dropped the price of entry from $349 to $299 (this doesn't count the launch of new editions of consoles with reduced feature sets, like the New Nintendo 2DS in 2017 or $249 all-digital Xbox One in 2019). This generation, we've seen something that would have been unheard of a few years ago: price increases for consoles, including $50 extra for the new OLED edition of the Nintendo Switch in 2021, a $50 price hike for the slimmer disc-drive-less version of the PlayStation 5 in 2023, and $80 to $100 price hikes for the exact same unimproved versions of the Xbox Series S and X earlier this week.

These price increases have multiple intertwining causes, some direct and some less so: inflation, pandemic-era supply crunches, the unpredictable trade policies of the Trump administration, and a gradual shift among console makers away from selling hardware at a loss or breaking even in the hopes that game sales will subsidize the hardware. And you never want to rule out good old shareholder-prioritizing corporate greed.

But one major factor, both in the price increases and in the reduction in drastic “slim”-style redesigns, is technical: the death of Moore’s Law and a noticeable slowdown in the rate at which processors and graphics chips can improve.

What is Moore’s Law?

Don’t let the name throw you: It’s not really a law! Moore’s Law is something in between “a goal” and “an observation,” coined by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965: that the number of transistors in a given chip would double roughly every year (later revised in 1975 to every two years).

Moore's Law held true over the next four decades thanks in part to dramatic improvements in the manufacturing processes used to make silicon chips. Chip fabricators like Intel and AMD and Samsung and TSMC—and many others that have come and gone—kept developing more and more advanced ways to cram more transistors into the same amount of physical space, making that continued doubling of transistor counts over time feasible.

Not everyone will declare in so many words that Moore’s Law is “dead,” and any given tech exec’s opinion on that says just as much about that exec’s motivations as anything else (Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, who can sell GPUs for more money if Moore’s Law is “dead,” will tell you it’s dead; Intel execs who are trying to convince you that Intel is on the road to being competitive manufacturer of high-end chips will contest that).

But the fact remains that progress in new manufacturing technologies has slowed, and developing new ones has gotten dramatically more time-consuming and expensive. And unless people find a way to make transistors sub-atomic, we'll hit the boundaries of actual laws sooner or later: the laws of physics.

How does this relate to game consoles? We're getting to that.

A side effect of fitting more transistors into a given area is that power usage also goes down, because you need to use less electrical current to switch those transistors on and off. Taking any given silicon chip and making it on a newer, more efficient manufacturing process is commonly called a "die shrink," because you're making a functionally equivalent silicon die that uses less physical space.

For computer processors and GPUs, those power savings are usually “spent” by adding transistors, either to improve performance or add new capabilities—that's why a processor from 2020 can perform dramatically better than one from 2010 and consume about the same amount of power.

But game consoles are meant to be static, stable targets for game developers to aim at, so that their internal testing of a game and how it runs is always indicative of how the game will run on everyone’s consoles.

So when you shrink the chips in a console, the benefit comes almost exclusively in the form of smaller physical chips that draw less power and put out less heat. You're also potentially getting more chips out of a single wafer of silicon, which theoretically can lower the price per chip (if the manufacturing process itself doesn't cost a ton more money).

Consolidation and miniaturization

Game consoles have benefited massively from those die shrinks, and those benefits were passed down to buyers in the form of streamlined hardware and lower costs. These changes are particularly pronounced once you get to the 3D home console era in the late 90s and early 2000s, when dramatic redesigns like the original PlayStation and PS2 Slim were possible within just a few years of the original console's launch.

Consider the PlayStation 2. Not all of the PS2 Slim's streamlining came from chip improvements—it also shed a full-sized 3.5-inch hard drive bay and a little-used IEEE 1394 port, and initially required an external power brick. But shrinking and consolidating the console's CPU, GPU, memory, and other components took the console from its original design in 2000, to the Slim in 2004, to an even lighter and lower-power version of the Slim that returned to using an internal power supply without increasing the size of the console at all.

Over that same span, the console's price dropped frequently and significantly, from $299 at launch to just $129 by 2006 (the price was lowered again to $99 in 2009, deep into the PS3 era).

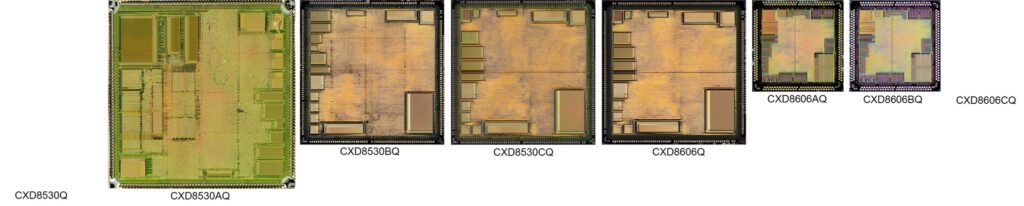

Or look at Microsoft's Xbox 360. Its external design didn't change as much over the years—the mid-generation "slim" refresh was actually only a little smaller than the original. But between late 2005 and early 2010, the CPU, GPU, and the GPU's high-speed eDRAM memory chip went from being built on a 90 nm process, to 80 nm, to 65 nm, and finally to a single 45 nm chip that combined the CPU and GPU into one.

Over that time, the system's power supply fell from 203 W to 133 W, and the base price fell from $300 to $200. The mid-generation 65nm refresh also substantially fixed the early consoles' endemic "red ring of death" issue, which was caused in part by the heat that the older, larger chips generated.

As you can see when comparing these various consoles' external and internal design revisions, shrinking the chips had a cascade of other beneficial and cost-lowering effects: smaller power supplies, smaller enclosures that use less metal and plastic, smaller heatsinks and cooling assemblies, and smaller and less complicated motherboard designs.

A slowdown of that progression was already evident when we hit the PlayStation 4/Xbox One/Nintendo Switch generation, but technological improvements and pricing reductions still followed familiar patterns. Both the mid-generation PS4 Slim and Xbox One S used a 16 nm processor instead of the original consoles' 28 nm version, and each also had its price cut by $100 over its lifetime (comparing the Kinect-less Xbox One variant, and excluding the digital-only $249 Xbox One). The Switch's single die shrink, from 20nm to 16nm, didn't come with a price cut, but it did improve battery life and help to enable the cheaper Switch Lite variant.

Sony and Microsoft have marginally tweaked the hardware inside the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series consoles since launching them, but as die shrinks have become rarer and more expensive to pull off, the benefits have become a whole lot less noticeable. Until recently, you could at least tell yourself that keeping the prices of these consoles stable during a 40-year inflation high could count as a "price cut" of sorts, but now that costs are going up, even that cold comfort is no longer available.

It's the same story we've seen in new PC CPUs and GPUs in recent years, too. In the mid-2010s, a new Nvidia GPU generation meant the same or better performance at lower prices than previous-generation cards; this decade, you mostly need to either pay more to get more, or you have to settle for minor improvements at similar prices. AMD has had to keep its nearly decade-old AM4 motherboard and CPU platform in circulation for years after technically "replacing" it, because socket AM5 boards and chips still aren't quite cheap enough to address the budget-to-midrange PC market.

We could still see prices come down gradually for all this tech in the coming years if trade deals are struck and cutting-edge manufacturing processes get cheaper. I'm not holding my breath! But the possibility still exists. Either way, though, it's clear that we can no longer assume by default that the patterns and precedents of the last 40 years will hold up.

Last week, I put in a pre-order for a Nintendo Switch 2. It's the first brand-new game console I've ever bought on the first day it was available. I figure the technology won't get much better and the price won't get any lower in the next couple years, and it might even go up. There used to be lots of benefits to waiting for this kind of thing—not anymore.

Hope you enjoyed this news post.

Thank you for appreciating my time and effort posting news every day for many years.

News posts... 2023: 5,800+ | 2024: 5,700+ | 2025 (till end of April): 1,811

RIP Matrix | Farewell my friend ![]()

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.