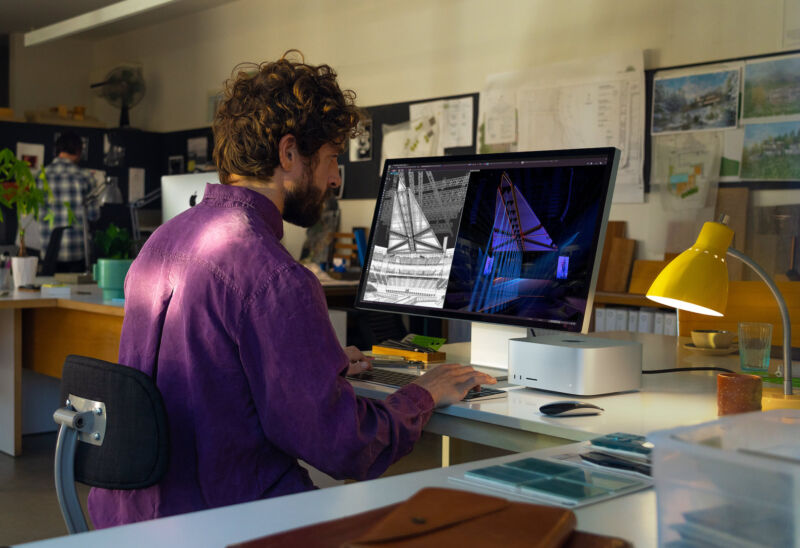

Apple's announcements of the Mac Studio, the Studio Display, and the new top-end M1 Ultra chip earlier this week focused on those devices' headlining features, but there are always more details to explore as people dig through the spec sheets and Apple responds to questions from the press. Ahead of our full reviews, we've compiled some of the most interesting details about the new hardware.

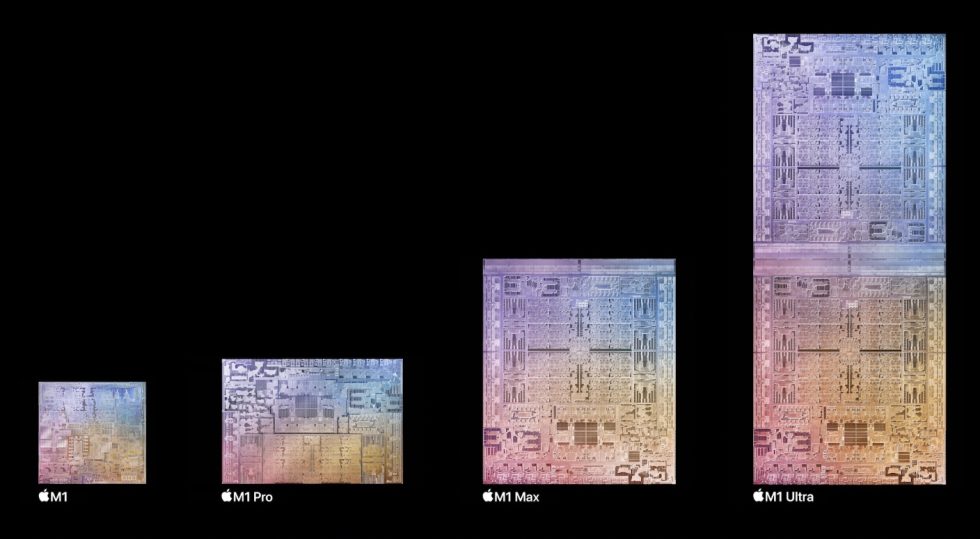

M1 Ultra: It's not really "chiplets"

When the M1 Ultra was announced, we speculated based on how Apple was describing it that the processor was using a chiplet-based design, connecting two separate M1 Max processor dies together using a high-speed interconnect like AMD's Infinity Fabric. That turns out not to be strictly true—the M1 Ultra will look like one big piece of silicon, just as it appears in Apple's render shots, two M1 Max chips packaged together with a silicon interposer between the two. ComputerWorld describes it as one large "840mm squared die."

The main risk with creating such a huge chip is that manufacturing yields will be low, as more surface area increases the likelihood that there will be a defect somewhere in the chip. But TSMC has been making M1-based chips on its 5 nm process for well over a year now, giving it plenty of time to optimize yields. And Apple is able to do some binning with the M1 Ultra (i.e., selling some chips with defects as lower-end models with the defective parts turned off), since there are versions with both 48 and 64 GPU cores.

The increased manufacturing complexity would explain why it costs so much to get a fully maxed-out M1 Ultra. Stepping up from the M1 Ultra with the 48-core GPU to the one with the 64-core GPU costs an extra $1,000. Compare that to the mere $200 it costs to upgrade the M1 Max from a 24-core GPU to a 32-core GPU.

Predictably, a genuine-looking results page for the Mac Studio and M1 Ultra appeared in the Geekbench online results database shortly after Apple's event ended. If the page is real, it helps to back up Apple's performance claims. Both its single and multi-core performance scores far exceed those of the 2019 Mac Pro's fastest 28-core Xeon W-3275M processor. A Mac Pro with that processor costs an eye-watering $13,000, compared to $4,000 for the M1 Ultra Studio model.

Geekbench gives us only a limited picture of a given device's performance, particularly for a pro-focused desktop like the Studio. The machine's ability to crunch on huge files for long periods of time will be just as important as its ability to run a benchmark app for two minutes. But that top-line number is impressive nevertheless.

Single-core performance isn't much different than it is for devices powered by the standard M1, like the Mac mini. This makes sense—the M1 Ultra bumps the core count way up, but the cores are still the same. It's an interesting contrast to Intel's and AMD's approach to single-threaded performance, though; both companies tend to nudge the peak single-core clock speeds upward in their high-end processors to help further differentiate them from cheaper models. It's also possible that trying to boost single-core clock speeds for higher-end M1 chips would blow Apple's power budget.

Studio Display: It works with Windows

Apple's new 5K Studio Display only lists Macs and iPads on its compatibility list, but nothing will prevent it from working with Windows PCs that can handle it. The fancy camera-panning Center Stage feature and True Tone support won't work, but the display itself, its speakers, and its webcam will all register to Windows PCs, and charging over USB-PD will presumably work for PCs as well. You will, however, need to connect the display to an Apple device to perform firmware updates.

We don't yet know the monitor's required PC specs. More modern computers with 11th- or 12th-generation Intel processors and Thunderbolt ports ought to be the safest bet. But whether the display will work with a regular USB-C port or a DisplayPort-to-USB-C connection remains to be seen. We'll do some testing of this in our review.

You can’t change your stand

The basic Studio Display stand can only tilt the screen up and down, and it doesn't enable VESA mounting for people who choose to use monitor arms or wall mounts. A height-adjustable stand for the monitor will cost you an extra $400 on top of the monitor's $1,599 starting price, but you can opt for a VESA mount instead of the regular stand at no additional charge.

The catch? You can't change the stand after you order the display. Most PC monitors have VESA mounting holes drilled into the back of the screen, or their default stands detach to expose the VESA mounting holes, letting you use the included stand for a while and install a monitor arm later if you like. No such luck with the Studio Display.

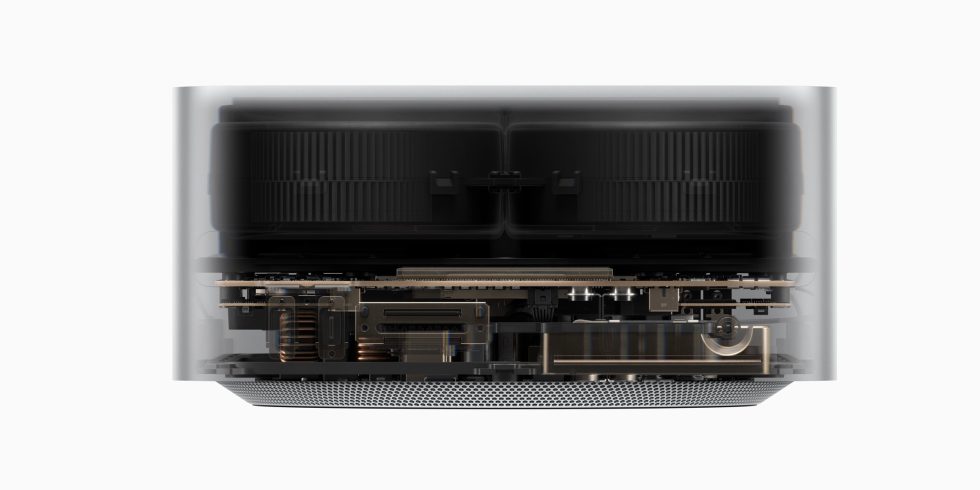

Mac Studio: M1 Ultra is heavy

Sure, the M1 Ultra is faster than the M1 Max (even though "Max" is short for "maximum," which is definitionally "the most something can possibly be"). But did you know that it's also heavier?

Well, specifically, its cooling apparatus is heavier. Though they're the same size, the M1 Ultra version of the Mac Studio weighs nearly eight pounds, two more than the version with the M1 Max. Apple says that's because it's using a copper heatsink to dissipate the M1 Ultra's extra heat, while the M1 Max uses an aluminum heatsink instead. Copper is more conductive than aluminum, but it's also denser, heavier, and more expensive, so it makes sense to use aluminum instead when you can get away with it. Many CPU fans for PCs try to split the difference, using copper cores or heatpipes for the bits that make contact with the CPU but aluminum for most of the cooler's surface area.

A PowerPC Easter egg

One other thing you might notice about that Mac Studio Geekbench entry is the Mac Studio's model identifier. These identifiers, usually the name of the system followed by two comma-separated numbers, are shorthand that Apple and macOS use to identify Macs in their code. This saves them the trouble of spelling out somewhat ridiculous consumer-facing names like "MacBook Pro (13-inch, 2016, Two Thunderbolt 3 ports)."

The first number in these modifiers refers to the generation of the system, while the second refers to a different model within a generation. Oddly, the Mac Studio's identifier is "Mac13,2" (presumably the M1 Max version is Mac13,1), suggesting that this all-new Mac is actually the 13th iteration of... something. But Apple has never just used a no-adjective "Mac" in any of its model identifiers.

If you look at EveryMac's long list of all of Apple's Mac model identifiers, you can find a possible explanation: Apple's last PowerPC G5 iMac was the "PowerMac12,1." Apple used to use "PowerMac" to identify all of its desktops during the PowerPC era, from the actual Power Mac towers to the iMac, the Mac mini, and the G4 Cube. If you took the PowerPC chip out of "PowerMac," you just get "Mac." It seems that Apple is making a subtle nod to the pre-Intel era in launching its first all-new Mac of the post-Intel era.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.