It's also worth stressing that while there are at least mildly compelling reasons for dropping support for older 4th- and 5th-gen Intel CPUs in Ventura, as best we can tell, those reasons don't really extend to most of the Skylake-based Macs. Intel still provides graphics driver updates and new microcode updates for all Skylake processors and integrated GPUs, while AMD still provides modern drivers for the dedicated Radeon Pro 400-series GPUs in the 2016 MacBook Pros (the Radeon R9 300 GPUs from the 2015 iMacs, admittedly, has been moved to AMD's legacy driver support model, so it could be more of a stretch).

The performance and feature gap between 6th-generation (unsupported) and 7th-generation (supported) Intel chips is also very small; 7th-generation chips increased clock speeds somewhat, and their GPUs included better support for encoding and decoding 4K video. Architecturally, though, the chips are nearly identical due to the problems Intel was having getting its next-generation manufacturing process off the ground at the time—some version of the Skylake architecture was included in 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th-generation Intel chips, and the 6th and 7th generations are especially similar. The Radeon Pro 500-series GPUs in the 2017 MacBook Pros are the same way, providing nigh-imperceptible improvements to the architecturally similar 400-series GPUs in the 2016 models.

Even moving down to more granular system components, iFixit teardowns for the 2016 and 2017 MacBook Pros reveal that these models are virtually identical in every way: the same Apple T1 chip, the same Intel Thunderbolt controllers, the same Wi-Fi and Bluetooth modules, and even the same power management controllers and NAND flash chips.

For the 2016 MacBooks and MacBook Pros in particular, I can't identify a compelling reason why Ventura wouldn't run just as well on them as it does on the 2017 models. It's possible that Ventura would run just fine on them with absolutely no additional drivers or model-specific effort from Apple because their CPUs and GPUs are so similar and they're supported by the same drivers. Absent some alternate explanation that Apple won't give me or anyone else, there's just no compelling technical reason not to support these Macs.

Extend security updates for older Macs

Apple dropped support for a fairly large number of iPhones and iPads in the move from iOS 12 to iOS 13, including the iPhone 5S, the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, the first-gen iPad Air, and two generations of iPad mini. But then, with little fanfare, Apple did something it had never done for older iDevices before: it continued to provide iOS 12 security updates specifically for those older devices, releasing them nearly in lockstep with iOS 13 and iOS 14 updates over the next two years.

Two years' worth of ongoing security updates is already Apple's standard practice for old macOS versions, so in that sense, the iOS 12 situation isn't remarkable on the Mac side. But if Apple really does want to wind down the Intel versions of macOS quickly, it could at least commit to a longer tail of security-only updates for the last few Intel-supporting macOS releases. This could help protect Intel Mac users who aren't yet ready to upgrade their machines while also freeing Apple from the burden of continuing to add and support new macOS features across multiple processor architectures.

Better communication about updates

Whatever Apple does, the company could help end users, IT workers, and security professionals by improving how it communicates about updates.

Right now, Apple is tight-lipped about virtually everything regarding the way it supports macOS. We can assume yearly updates because Apple has released them that frequently in the past, and we assume that each macOS version will get around two years of security updates because that's how Apple has handled it in the past. But Apple carefully avoids publishing "end of support" dates for any of its software products, unlike Microsoft. You can't be sure when your device will stop getting security updates or what patches it will be missing when support ends. And every time Apple announces a new version of macOS, Apple risks surprising some subset of Mac users by dropping their hardware from the support list without warning.

Apple is secretive about its future plans, even compared to other tech companies; it's baked into the company's communications strategy, and it's clearly not going to change. Maintaining a veil of secrecy around unannounced products is justifiable for a publicly traded company that is trying to get and keep a leg up on its competitors. Maintaining that same veil of secrecy around software update timelines for five-year-old devices makes way less sense.

Right now, Apple is refusing to communicate anything about its software support timeline, and it's ending support for older Intel Macs years earlier than it was in the very recent past. Apple needs to fix at least one of these problems, lest owners of late-Intel-era Macs come away feeling burned.

Update: An earlier version of this piece didn't accurately describe how older operating systems will handle edited and unsent iMessages from Ventura or iOS 16; that description has been corrected.

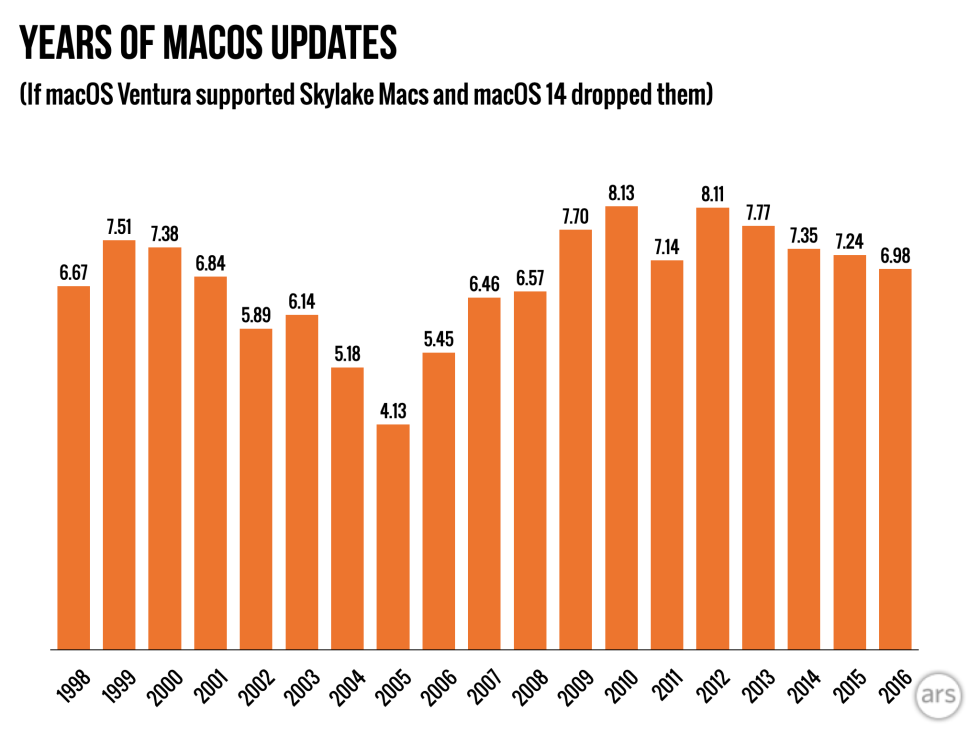

Notes on data collection

-

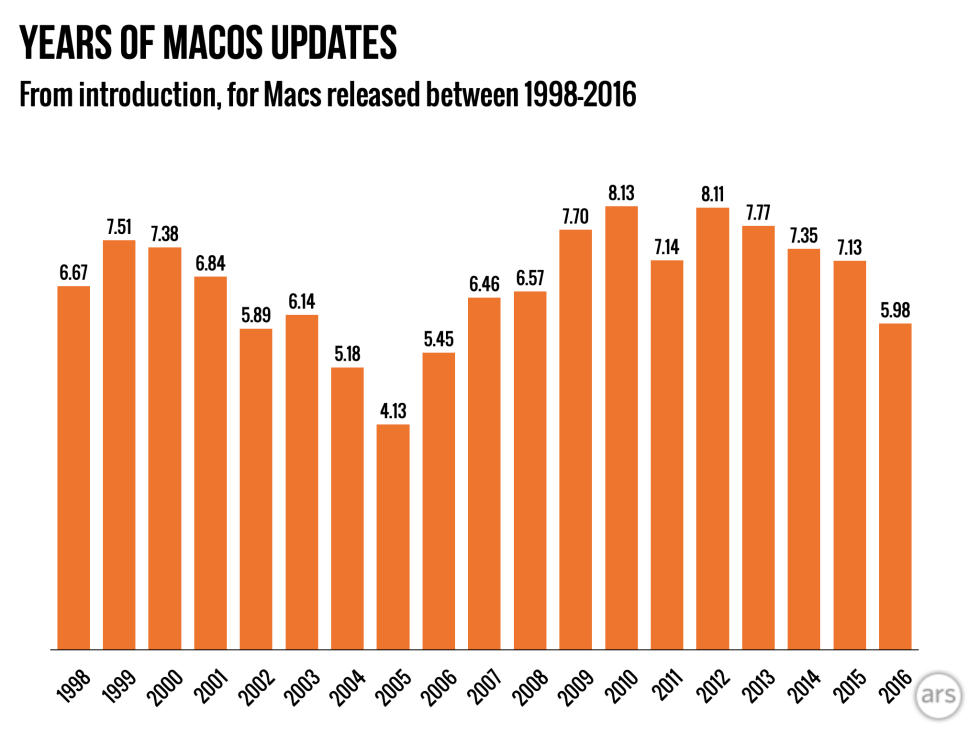

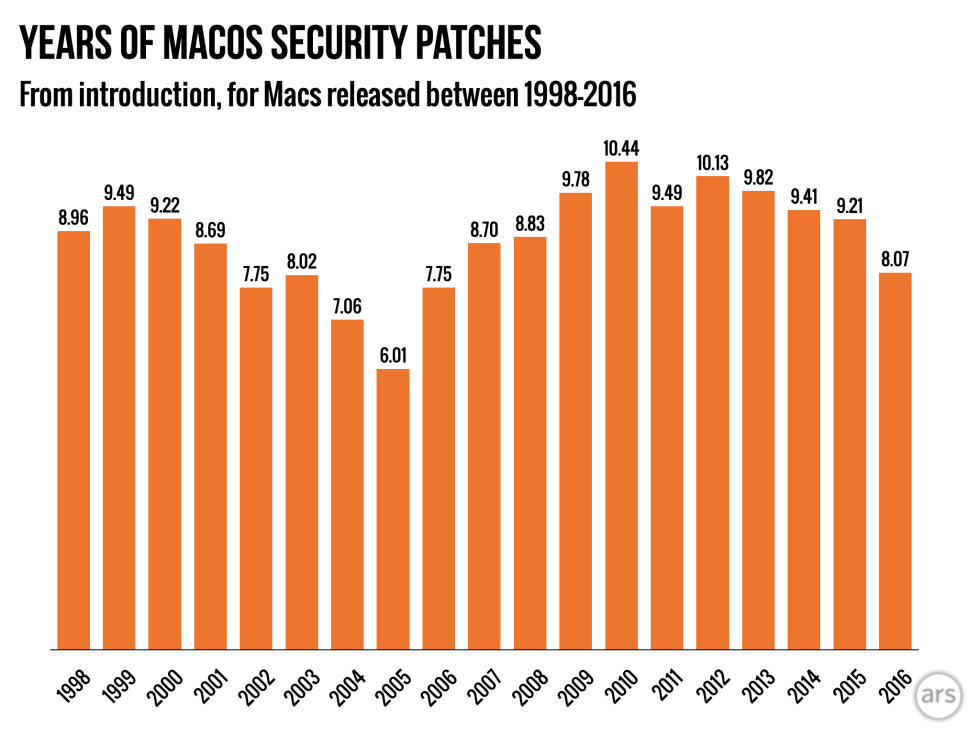

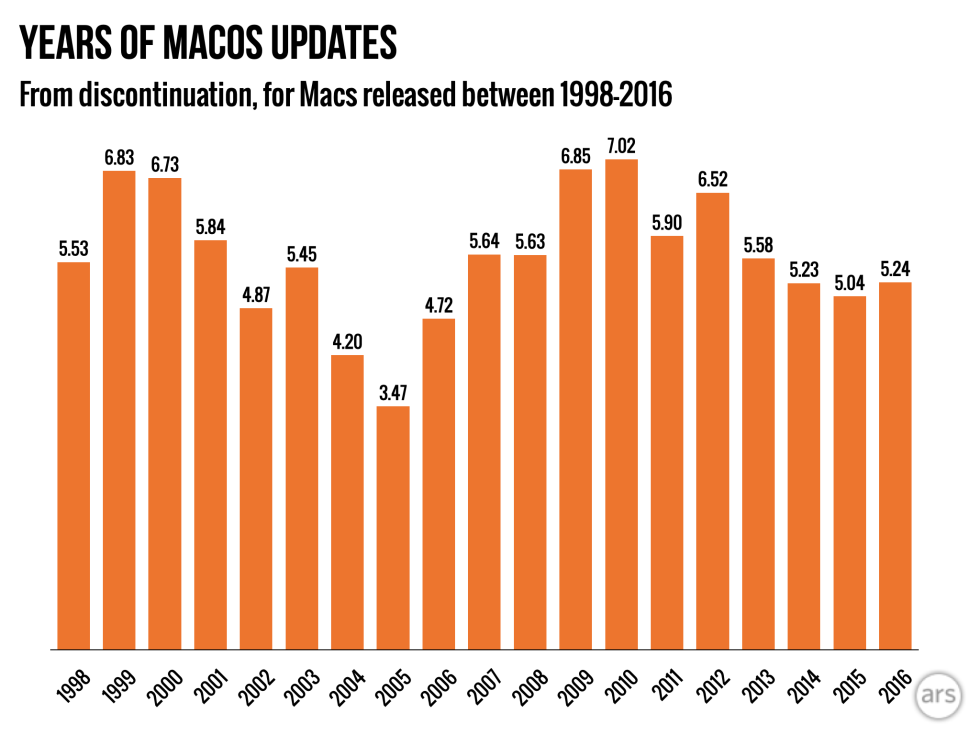

We treat each Mac model identifier as a separate device, even if they were introduced, discontinued, and dropped from support at exactly the same time. This happened with many generations of 11-inch and 13-inch MacBook Airs, 21- and 27-inch iMacs, and others.

-

Some models could be upgraded beyond their normal life cycles using upgrades or software workarounds, like installing a CPU upgrade, disabling installer compatibility checks, or using patching tools or alternate bootloaders. For consistency's sake, we're using official support dates for unmodified hardware and software, since that is what a typical user would experience.

-

When calculating the length of time each OS was supported with security updates, we used the date of the last regularly released Security Update for each OS, as listed on Apple's Security Updates page. Some OSes received updated versions of iTunes and Safari for a bit longer, or received limited one-off fixes after regular updates had dried up; we didn't count these. We also don't count additions to Apple's behind-the-scenes XProtect malware blacklist, which periodically gets new updates on Macs going all the way back to El Capitan (10.11).

-

Some models continued to be sold to educational institutions for a while after they were discontinued for everyone else. We're using the dates they were discontinued for the public, as listed on EveryMac. We also didn't include models sold exclusively to educational institutions, like mid-2009 iMac.

-

The "eMac," a cheaper CRT alternative to the LCD iMac G4, is included with the other iMacs.

-

Some models received a mid-cycle refresh that bumped individual specs but didn't change the model identifier. For those systems, we used the date that the first revision was introduced and the date that the last revision was discontinued, since macOS makes no distinction between them.

-

We didn't count Xserve server hardware.

-

For Macs that can't run Ventura but are running a currently supported macOS version (as of this writing, Catalina, Big Sur, and Monterey), we've extrapolated end-of-support dates based on Apple's standard practice of providing security updates to all macOS versions for two years after they are replaced. The actual dates may vary by a month or two.

Listing image by Aurich Lawson

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.