Why multifactor authentication based on one-time-passwords and push notifications fails.

An entire cottage industry has formed around phishing attacks that bypass some of the most common forms of multifactor authentication (MFA) and allow even non-technical users to quickly create sites that defeat the protections against account takeovers.

MFA works by requiring an additional factor of authentication besides a password, for instance, a fingerprint, face scan, or the possession of a digital key. In theory, this prevents attackers from accessing an account even after they phish a victim’s username and password. Most often, the second form of authentication comes in the form of a one-time passcode that is sent to the user by text message or email or is generated by an authentication app that the user has already set up.

Adversary in the middle

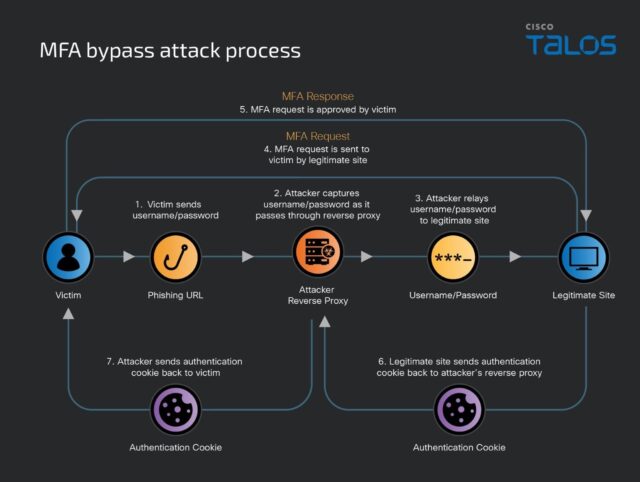

As detailed on Thursday by Cisco Talos, an entire ecosystem has cropped up to help criminals defeat these forms of MFA. They employ an attack technique known as an adversary in the middle. The tools provide phishing-as-a-service toolkits that are marketed in online crime forums using names including Tycoon 2FA, Rockstar 2FA, Evilproxy, Greatness, and Mamba 2FA.

The products provide all the code someone needs to set up a proxy server that sits between the victim and the site they’re trying to log into. The toolkits also provide templates for creating convincing-looking phishing pages.

The attack starts by sending the victim a message enticing them to log into their account, often by falsely claiming it has been compromised and needs to be locked down immediately. The hoax message provides a link that looks similar to the legitimate account URL, but in actuality, is slightly different.

For instance, rather than the URL being https://accounts.google.com/—the real link for logging into a Google account—it’s something like https://accounts.google.com.evilproxy[.]com. In many cases, the victim will be so consumed with the anxiety over the purported account compromise that they won’t spot the incorrect URL.

The malicious link leads to the attacker’s proxy server that, thanks to the phishing-as-a-service toolkit, looks identical to the real Google login site (except for the URL displayed in the address window). The user then enters their username and password.

The proxy then forwards the credentials to the real Google site. Google will then send the proxy server an MFA request, and the proxy server sends it back to the victim, who is expecting it since they believe they’re trying to log into the legitimate Google page. The victim then sends the MFA code to the proxy server, which sends it to the real Google site. Alternatively, the user clicks a push notification displayed on their phone. In either case, the attacker has successfully compromised the account even though MFA was turned on.

When your phishing protection is phishable

The problem with these forms of MFA is that the codes themselves are phishable, since they come in the form of numbers, and occasionally other characters, that are just as easy for the attacker to copy and enter into the site as passwords are. The effect is the same in the event that the MFA is based on push notifications, since the victim clicks the button. And given the ease of using the phishing toolkits, even technical novices can create a legitimate-looking login page and a proxy server.

These sorts of adversary-in-the-middle attacks have grown increasingly common. In 2022, for instance, a single group used it in a series of attacks that stole more than 10,000 credentials from 137 organizations, and led to the network compromise of authentication provider Twilio, among others.

One company that was targeted in the attack campaign but wasn’t breached was content delivery network Cloudflare. The reason was its use of MFA based on WebAuthn, the standard that makes passkeys work. Services that use WebAuthn are highly resistant to adversary-in-the-middle attacks, if not absolutely immune. There are two reasons for this.

First, WebAuthn credentials are cryptographically bound to the URL they authenticate. In the above example, the credentials would work only on https://accounts.google.com. If a victim tried to use the credential to log into https://accounts.google.com.evilproxy[.]com, the login would fail each time.

Additionally, WebAuthn-based authentication must happen on or in proximity to the device the victim is using to log into the account. This occurs because the credential is also cryptographically bound to a victim device. Because the authentication can only happen on the victim device, it’s impossible for an adversary in the middle to actually use it in a phishing attack on their own device.

Phishing has emerged as one of the most vexing security problems facing organizations, their employees, and their users. MFA in the form of a one-time password, or traditional push notifications, definitely adds friction to the phishing process, but with proxy-in-the-middle attacks becoming easier and more common, the effectiveness of these forms of MFA is growing increasingly easier to defeat.

WebAuthn-based MFA comes in multiple forms; a key, known as a passkey, stored on a phone, computer, Yubikey, or similar dongle is the most common example. Thousands of sites now support WebAuthn, and it’s easy for most end users to enroll. As a side note, MFA based on U2F, the predecessor standard to WebAuthn, also prevents adversary-in-the-middle attacks from succeeding, although the latter provides flexibility and additional security.

Post updated to add details about passkeys.

Hope you enjoyed this news post.

Thank you for appreciating my time and effort posting news every day for many years.

News posts... 2023: 5,800+ | 2024: 5,700+ | 2025 (till end of March): 1,357

RIP Matrix | Farewell my friend ![]()

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.