Australia's unique use of facial recognition technology has caused controversy and stoked privacy fears, but there is a chance that it could become a world leader in regulating its use.

If a person in Western Australia contracts Covid-19, they must remain in home quarantine for the following seven days – as do their close contacts. The police check up on their whereabouts by sending periodic text messages and require a selfie to be sent back to them within 15 minutes. The police use facial recognition technology and GPS tracking to determine if the person who took the selfie is at home. If they are not, they quickly follow up with a knock on the door and a potentially hefty fine.

The G2G app by local tech start-up Genvis has been used by more than 150,000 people in the state since it was rolled out in September 2020. The same technology, albeit provided by different companies, has been piloted in the states of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. Australia stands out as the only democracy to use facial recognition technology to aid Covid-19 containment procedures while other countries were pushing back against the idea of such surveillance.

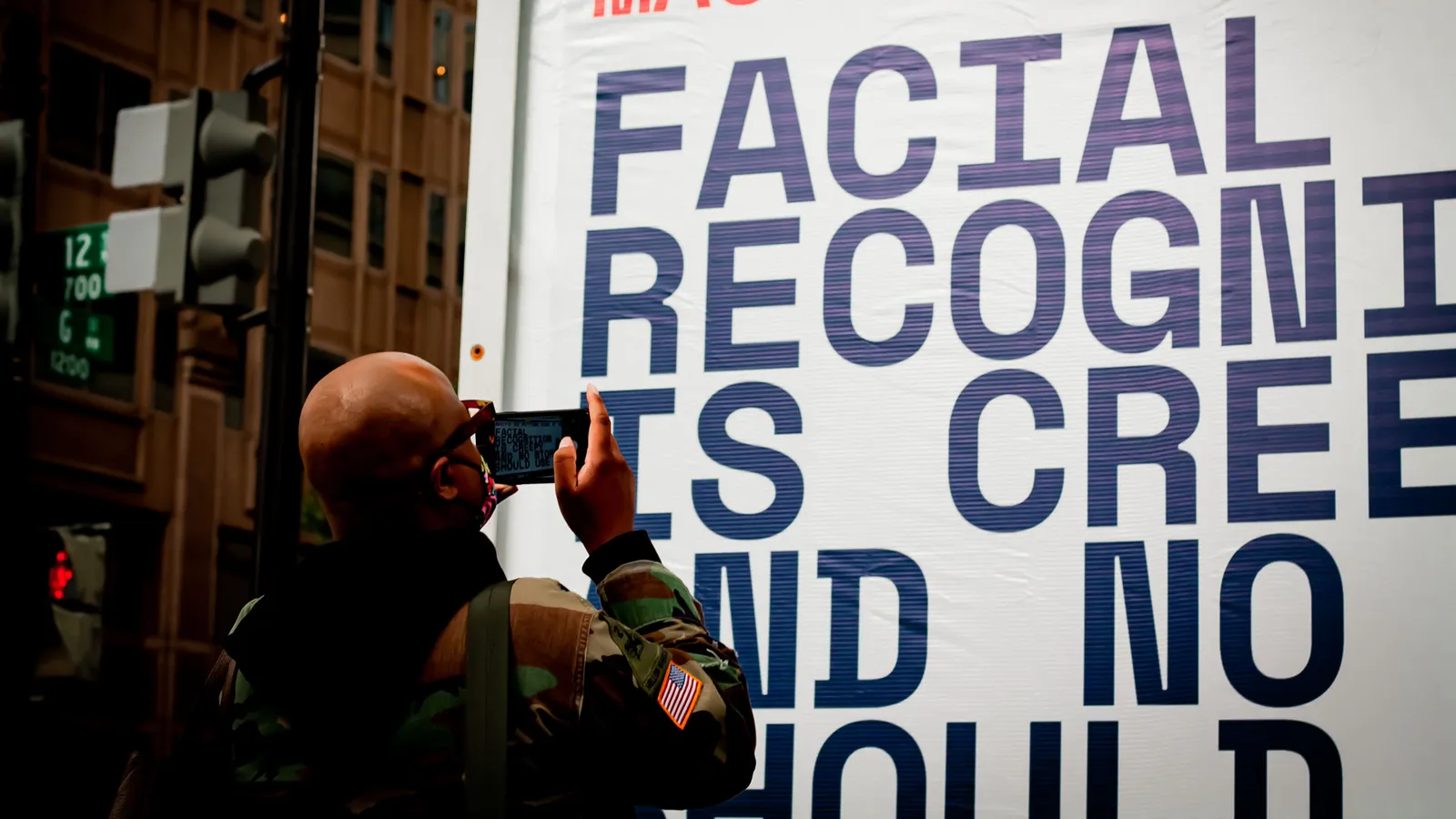

San Francisco was the first city in the US to introduce a moratorium against police using facial recognition in May 2019. It was quickly followed by Oakland, also in California, and Somerville in Massachusetts. Amazon, Microsoft, IBM and Google have declared they will not sell their facial recognition algorithms to law enforcements agencies until there is a federal law in place. In November 2021, Meta said that Facebook would delete one billion "faceprints" and cease using the technology for the purposes of tagging people in photos.

The Australian Human Rights Commission has called for a moratorium on the technology until Australia has a specific law to regulate its use. Human rights campaigners say there is potential for the personal data obtained to be used for secondary purposes, and that it is a slippery slope towards becoming a surveillance state. Groups such as Amnesty warn that the use of facial recognition leads to racial discrimination.

"The pandemic created all these new justifications for using facial recognition technology," says Mark Andrejevic, a professor of media studies at Monash University in Melbourne and the author of a forthcoming book titled Facial Recognition. "Everything went online and organisations were trying to make things work very quickly. But the implications haven't been thought through. Do we want to live in a world where everything is rendered and there are no private spaces? It creates a whole new level of stress that does not lead to a healthy society."

There has been significant push back from the public and campaigners over the use of facial recognition technology (Credit: Fight for the Future)

Consent is needed for the G2G app to be used, and it was also needed in the aftermath of Australia’s Black Summer bushfires of 2020, when those who had lost their identification papers used facial recognition to qualify for disaster relief payments. But there have been cases of facial recognition technology being used covertly.

In October, convenience store group 7-Eleven was found to have breached their customers' privacy by collecting faceprints from 1.6 million Australian customers when they completed satisfaction surveys. The faceprints were purportedly obtained in order to obtain demographic profiles and prevent staff from gaming the surveys by boosting their ratings. It did not receive a fine.

Australia's Department of Home Affairs began building a national facial recognition database in 2016, and it appears poised to roll it out. In January, it put out a tender for a company to "build and deploy" the data.

"Facial recognition is on the cusp of relatively widespread deployment," says Andrejevic. "Australia is gearing up to use facial recognition to allow access to government services. And among law enforcement agencies, there's definitely a desire to have access to these tools."

Most state governments have provided the central database with their residents' driver's licences, and the database also stores visa and passport photos.

A law to govern facial recognition technology was proposed back in 2019, but it was shelved after a parliamentary committee review found that it lacked adequate privacy protections. Among its strongest critics was the then Australian Human Rights Commissioner, Edward Santow.

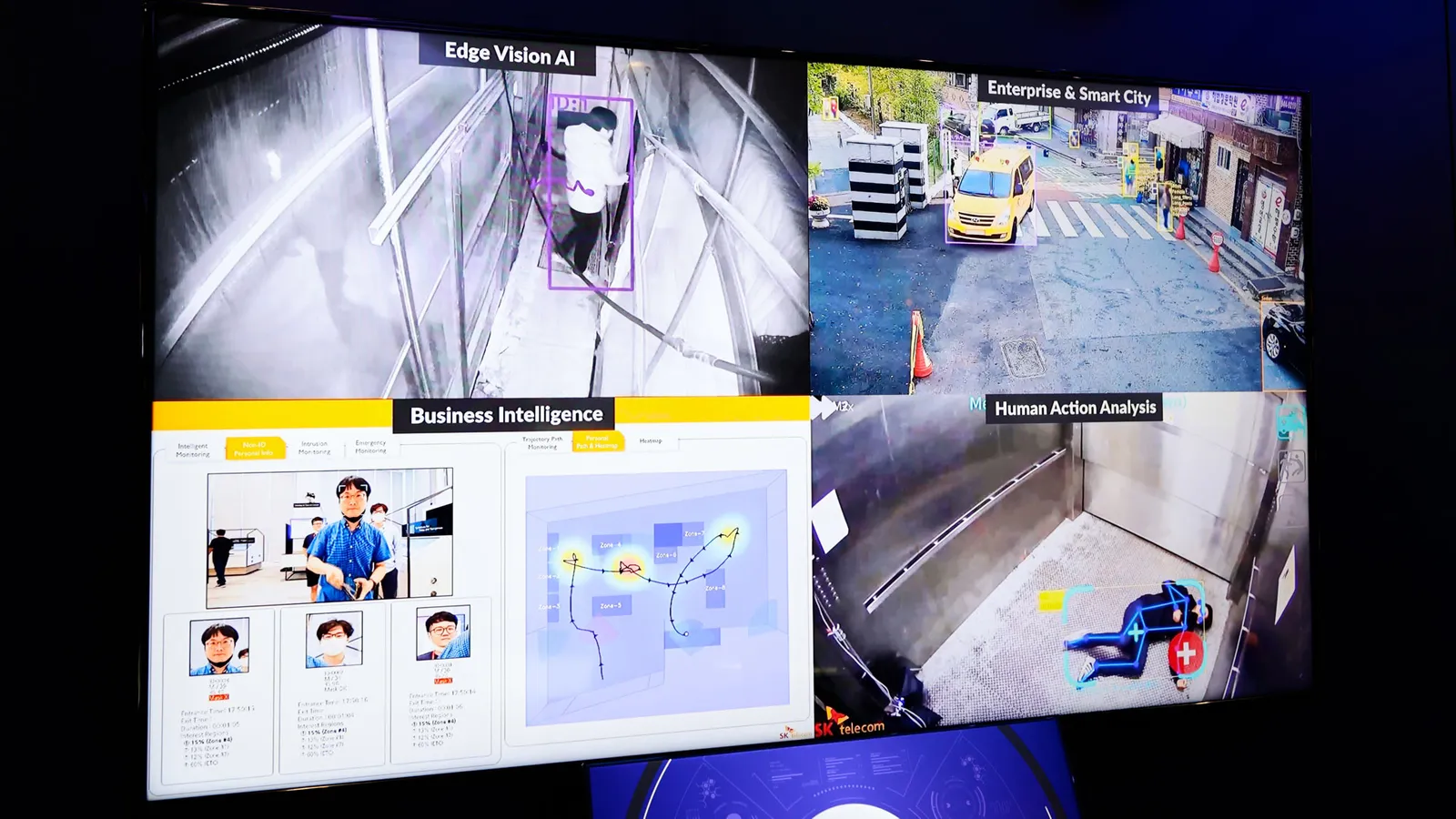

A prototype facial recognition technology demostrates how it could be used to detect people in distress (Credit: Getty Images)

"We're now in the worst of all situations where there's no dedicated law, so we're dealing with a few piecemeal protections that are not completely effective and are certainly not comprehensive," says Santow. "And yet the technology is continuing to be deployed."

Santow is working on ways to make the privacy provisions more robust, with his team at the University of Technology in Sydney.

A varied global response

Part of the project involves examining other countries' attempts to regulate facial recognition technologies. There are starkly different approaches around the world. The most common is to rely on a handful of limited privacy protections that Santow says fail to adequately address the issue; that’s the case in Australia.

"No country in the world has got it right," says Santow. "If [the privacy protections were suitable], this project would be a really simple one."

Leila Nashashibi is a campaigner at US-based advocacy group Fight for the Future, which is striving to achieve a federal ban on facial recognition and other forms of biometric identifiers.

"Like nuclear energy and biological weapons, facial recognition poses a threat to human society and our basic liberties that far outweigh any potential benefits," she says. "Facial recognition is unlike any other form of surveillance because it enables automated and ubiquitous monitoring of entire populations, and it can be nearly impossible to avoid. As it spreads, people will be too afraid to participate in social movements and political demonstrations. Free speech will be chilled."

Scraping social media for faceprints

The most prominent facial recognition technology provider, US company Clearview AI, appears not to be deterred by the lawsuits and hefty fines it is amassing in a variety of jurisdictions. It first attracted media attention when a billionaire used it to identify his daughter's dinner date, and it is currently being used by the Ukrainian government to identify dead Russian soldiers. Their families are notified over social media, with the photos sometimes sent as an attachment.

Facial recognition creates actionable information in real time in order to pre-empt crime – Mark Andrejevic

It is also seeking for its technology to be used in schools in the United States as a "visitor management system", which they believe could be used to help prevent school shootings by recognising the faces of expelled students, for example. Facial recognition and object recognition technology has been trialled at various schools already by different providers, including object recognition that could identify a concealed weapon.

"Clearview AI is exploiting people's terror and trauma by saying that surveillance and policing is the answer," says Nashashibi.

Clearview AI's Australian CEO and founder Hoan Ton-That disagrees. He says that facial recognition technology has great potential for crime prevention, because It can ensure that only authorised people have access to a building such as a school.

"We have seen our technology used with great success by law enforcement to stop gun trafficking, and we are hopeful that our technology can be used to help prevent tragic gun crimes in the future," he says.

In Australia, facial-recognition technology is being used at a number of stadiums to prevent terrorist suspects or banned football hooligans from entering. Andrejevic believes the use of facial recognition as a security measure is a significant step-up in surveillance and requires careful consideration.

"CCTV is often criticised for only allowing evidence after the fact, whereas facial recognition creates actionable information in real time in order to pre-empt crime," he says. "That's a very different conception of security."

Live facial recognition is already used by some police forces around the world. London's Metropolitan Police, for example, uses it to monitor specific areas for a "watchlist" of wanted offernders or people who might pose a risk to the public.

Facial recognition data is stored as a string of code called a biometric marker (Credit: Alamy)

Clearview has created a searchable database of 20 billion facial images, largely by scraping photos from social media without consent.

Ton-That has said the company will not work with authoritarian governments such as China, North Korea and Iran. However, it has encountered problems in some democracies. It has been banned in Canada and Australia and on 24 May, the UK's Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) fined it more than £7.5m (US$9.1m), following a joint investigation with the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. It was ordered to delete the data of British residents from its systems. In December 2021, France's privacy watchdog found that Clearview breached Europe's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Santow says that the aim in Australia is to develop a nuanced approach which encourages the use of positive applications and to impose guardrails to prevent harms. The worst-case scenario would be to replicate the "social credit" system in China, where individuals and organisations are tracked by the government to determine their "trustworthiness".

"In determining whether a use is beneficial or harmful, we refer to the basic international human rights framework that exists in almost every jurisdiction in the world," says Santow.

For example, the law would require free and informed consent for facial recognition to be used. However, if the technology was causing discrimination to occur through its inaccuracy in relation to certain groups, the consent would become irrelevant. As Santow says: "You cannot consent to being discriminated against.”

Increasingly sophisticated and powerful

"In the next couple years, we're going to see a big shift away from people using passwords, which are totally insecure. Biometrics will become the default," says O'Hara.

Facial recognition works by dividing the face into a series of geometric shapes and mapping the distances between its "landmarks", such as the nose, eyes and mouth. These distances are compared with other faces and turned into a unique code called a biometric marker.

"When you use a facial recognition app to open your phone, it isn't a picture of your face that your phone stores," explains Garrett O'Hara, field chief technologist at security company Mimecast. "It stores an algorithmic derivation of what your face is mathematically. It looks like a long code of letters and numbers."

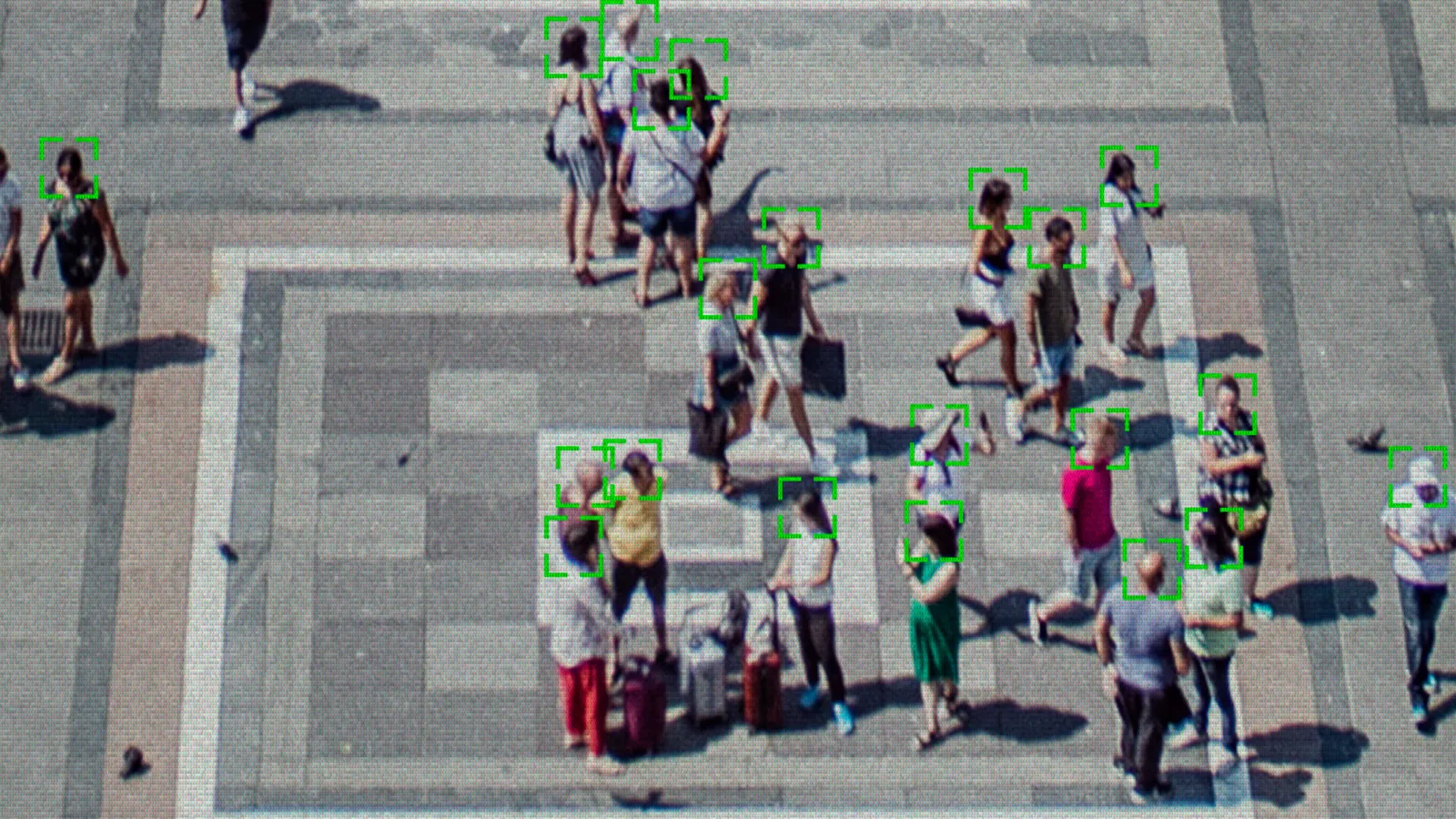

Facial recognition has come a long way since it was first developed in the 1960s, although the error rate varies significantly between different systems used today. At first it was unable to distinguish between siblings, or the changes in a person's face as they aged. It is now so sophisticated that it can identify someone wearing a facemask or sunglasses, and it can do so from more than a kilometre away.

The best face identification algorithm has an error rate of just 0.08%, according to tests by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. However, this level of accuracy is only possible in ideal conditions, where the facial features are clear and unobscured, the lighting is good and the individual is facing the camera. The error rate for individuals captured "in the wild" can be as high as 9.3%.

"It's incredibly useful technology. But if somebody had asked us 20 years ago when the worldwide web was starting up if we wanted to want to live in a world where our interactions and activity were collected and tracked, the majority of us probably would have said that it sounded creepy," says O'Hara. "We're now replicating the tracking of online space to include physical space as well. And we're not asking the questions about it that we should be."

One of its most problematic aspects is its potential for racial discrimination and bias. Most facial recognition applications were initially trained using data sets that were not representative of the full breadth of the community.

"In the early days, the datasets being used were all taken from white males or white people in general," says O'Hara. "And clearly, it leads to problems when you've got people of colour or of different ethnicities or backgrounds that don't match the training models. At the end of the day, it's just mathematics. This is the problem."

Without representative data, facial recognition technology has been found to racially discrimintate, and misidentify women and people with disabilities (Credit: Getty Images)

As a result, facial recognition systems are prone to mistakes when attempting to recognise those belonging to an ethnic minority group, women, people with a disability and the elderly. Its use has resulted in false arrests and other life-altering consequences, points out Nashashibi.

Deep fakes take fraud to new heights

Whether it is a thumb print, iris scan, gait analysis or capillary reading, no form of biometrics is fool proof. As the technology becomes more sophisticated, so do the hackers' attempts to manipulate it for their own gain. Deep fakes have emerged as an evolution of fraud techniques, particularly in relation to digital facial recognition (that is to say, photos).

"It used to take several hours to create a deep fake using animation tools – now it takes a couple of minutes," says Francesco Cavalli, the co-founder of Sensity AI in Amsterdam. "All you need is one photo to create a 3D deep fake. This means that the fraudsters can scale their operations and attacks are skyrocketing. You don't even need to be developer or an engineer. You can do it yourself. There are tons of apps that allow you to replicate anyone's face."

Sensity AI helps governments, financial institutes and even dating websites to spot fraudulent applications, whether to obtain Covid-19 relief payments, store laundered money in a bank account or to blackmail someone on Tinder. The infrared liveliness test determines body temperature and blinking when someone takes a photo online, which means that a photo of a "synthetic" person will be detected.

"At some point the fraudsters work out how to fool our different models, so we need to continuously come up with new techniques," he says.

Despite the challenges in the path towards regulation to date, Santow is optimistic that Australia could become a world leader in regulating facial recognition. "I can't speak on behalf of the federal and state governments. But I know that they understand there are strong community concerns and there is a need to build trust in the technology."

"Australia could provide a good model for a number of reasons," he adds. "We have a strong institutional and corporate respect for human rights. It may not be perfect, but it is fundamental to who we are as a country. We're also a sophisticated developer and adopter of technology."

"I perceive the greatest challenge not to be drafting a watertight law, but in making sure that the law itself isn't ignored."

- Karlston

-

1

1

Recommended Comments

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.