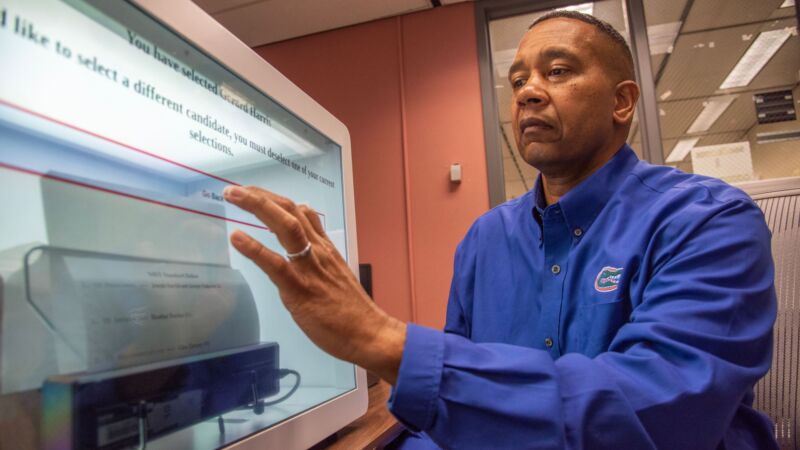

The machine also has some more distinctive security features. The touchscreen is transparent, allowing voters to watch the machine print their ballot, in real-time, and notice any issues. The whole machine is also encased in fully transparent glass, making it difficult to insert, say, a malicious USB drive undetected. And the machine’s operating system, software, printer connection, and ballot information are stored on a read-only Blu-ray Disc. Unlike a typical hard drive, which voting technology skeptics say could be manipulated to change a person’s votes, the disc cannot be overwritten, modified, or changed in any way. “I have taken away that ability,” said Gilbert. “You cannot change it.”

To further ensure that the USB ports can’t be used to upload mischievous code, Gilbert’s machine reboots after every cast vote. “That caveat blows out a whole lot of their issues,” he said. “No software can persist, right?”

Like most BMDs today, the machine also produces a paper ballot that can be audited. One longstanding concern about these paper trails is that voters don’t actually verify whether what’s printed on their ballot matches what they selected on the machine. If that’s the case, then audits are no use.

This is why Gilbert’s machine is so innovative, he said. The transparent touchscreen forces voters to look directly at the paper being printed, making it far more likely that voters will notice any tampering. And if that happens, he said, the voter can raise an alarm.

By early May, Gilbert said, he had emailed about a half-dozen experts, including Appel and Harri Hursti, the co-founder and co-organizer of the Voting Machine Hacking Village at DEF CON, the annual hacking conference in Las Vegas. He’d issued his challenge: Could they hack the machine?

DEF CON, in particular, seemed like the perfect opportunity for Gilbert to showcase his BMD.

According to a 2017 report written by Hursti and several collaborators, the Voting Village was launched in 2017 “to highlight cyber vulnerabilities in U.S. election infrastructure.” At the gathering, attendees have the tools, access, and free time to unscrew, disassemble, and essentially destroy all of the machines on-site. The event sometimes produces viral content, like a 2018 Twitter video in which hacker Rachel Tobac says she’s gained administrator access on a voting machine used in 18 states. “Requires no tools and takes under 2 minutes,” Tobac wrote on Twitter. “I’m concerned for our upcoming elections.”

Hackers there do exactly what Gilbert had been asking for—spend days tearing machines apart, free of charge—and their confidence that all BMDs are insecure rivals Gilbert’s confidence that his is not.

“We know every single machine in this room can be hacked,” Hursti said at the start of the convention in August 2021. “And every future machine can be hacked.”

In addition, DEF CON attendees habitually criticize the machine vendors for keeping their code secret. Not only is Prime III open source, but Gilbert’s BMD, with its transparent casing and automatic reboot after every vote, would present a unique challenge.

The DEF CON culture has frustrated some observers. "At some point, you have to move beyond just the constant critiquing and move on to productive solutions," said Amber McReynolds, the former director of elections for the City and County of Denver and a current member of the Postal Service Board of Governors. Otherwise, she said, you risk having your research weaponized by people bent on discrediting the whole system. "I'd like to see the community of election security professionals be more thoughtful about the downstream impacts of their comments and their work on election officials, and also democracy as a whole."

By September, Gilbert still hadn’t heard from Hursti. In fact, nobody had agreed to test the machine.

When Undark reached out to the experts Gilbert had originally contacted, they offered different explanations for their silence. One said that he had retired. A second was in the hospital. Hursti said that Gilbert had emailed his personal account, not the official one for DEF CON’s voting village. Asked whether he would include the machine in next year’s event, Hursti did not respond to repeated messages from Undark. The day before the publication of this story, he wrote to clarify that Gilbert's machine would be welcome at next year’s convention, provided that he followed certain DEF CON policies, including that the hackers not be required to sign non-disclosure agreements.

Appel declined to test the machine, saying he didn’t have the resources to give it a thorough vetting. But he had seen the video of the device in action and heard Gilbert give a presentation on the new model. It was a good design idea, he said, and the lack of a hard drive provides fewer attack surfaces for a hacker to exploit. The device, he added, is addressing a problem with ballot-marking devices that nobody else has really tried to tackle.

Still, Appel said, he is skeptical of the very idea of unhackability. And he imagined scenarios during which, he said, Gilbert’s design might flounder. In a blog post published in April of last year, for example, he wrote that the system depends a great deal on human voters being prompted to review their votes. A subtle hack, Appel suggested, could simply remove that prompt. “This gives the opportunity to deliberately misprint in a way that we know voters don’t detect very well,” he wrote.

Appel brought up another scenario: Say that a voter tells a poll worker that the machine printed the wrong name on the ballot. Gilbert has prepared for this scenario: It’s possible to compare the master disc to the one in the machine to detect if there’s fraudulent code. Assume that the poll worker is able to execute that plan perfectly during the confusion of Election Day, and it reveals that the machine’s been tampered with. What then?

It’s unclear whether Gilbert’s machine will ever find wider use. Dan Wallach, a computer scientist at Rice University, said the machine was a promising step forward. Still, he voiced concerns about the durability of the machine’s parts. Appel pointed out that any new technology will face issues in being scaled for mass production and require training and for voters and poll workers.

There are other hurdles, too. For potential newcomers to the industry, it’s tough to break in, said Ben Hovland, a commissioner with the Election Assistance Commission, which was originally created by HAVA to enact the law’s requirements, including distributing the federal funding for machines. For starters, the industry isn’t that big. “While there are a lot of jurisdictions all over the country, there’s a fixed amount of equipment to sell,” he said.

“And if the jurisdiction recently bought equipment, they may not be looking for 10 years, maybe more,” he continued.

Most states also require machines to be certified, which the vendors must pay for. Under EAC guidelines, Gilbert could have to fork over hundreds of thousands of dollars to undergo that process.

Moving forward, Gilbert is planning to write a new paper detailing his design, and still hoping to find a hacker willing to test out the machine. The experience has left him sounding jaded about the world of election hacking — a world, he suggested, that often seems focused more on performatively tearing apart machines than actually working toward solutions.

“They only look at things they know they can break,” Gilbert said.

“If you have something that you can’t on the face of it figure out before you touch it,” he continued, “they’re not going to touch it.”

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.