The Milky Way is full of planets, and it's very likely that they are plentiful in other galaxies as well.

But there's a big difference between it being likely that planets exist outside of our galaxy and having evidence that they do. And the methods that have allowed us to spot planets in the Milky Way simply won't work at such vast distances. But this week, researchers announced that a technique they proposed may have turned up the first indication of a planet in another galaxy. The data was sitting in the archives of a couple of X-ray telescopes.

Long-distance eclipse

Almost every planet we know about was identified by one of two methods: either by watching a planet's gravitational influence on the wavelengths of light produced by a star or by watching the reduction in light as it passes between us and its host star. At the moment, we don't have hardware with the resolution needed for these techniques to work well with other galaxies, which generally appear as collections of stars so dense that distinguishing one star from another is nearly impossible.

In 2018, Nia Imara and Rosanne Di Stefano proposed a variation on existing techniques that might work with distant galaxies. The trick is that it won't work with visible wavelengths of light.

Consistent X-ray sources in galaxies are relatively rare, meaning that we can point X-ray telescopes at a galaxy and resolve individual sources. Many are also compact, allowing a planet to obscure them, even if the planet is orbiting at a significant distance. They're generally composed of the remains of a star, such as a neutron star or black hole, that is powering X-ray emissions by stealing matter off a nearby companion. The process of feeding on this matter is steady enough that these sources tend to emit steadily for long periods of time.

So if the X-ray source were to suddenly wink out and return, Imara and Di Stefano concluded, it would likely be due to an object blocking it along the line of sight from Earth. There are a number of potential bodies that could cause this effect, including the star it's drawing matter from. Or it could be an exoplanet.

From hypothesis to data

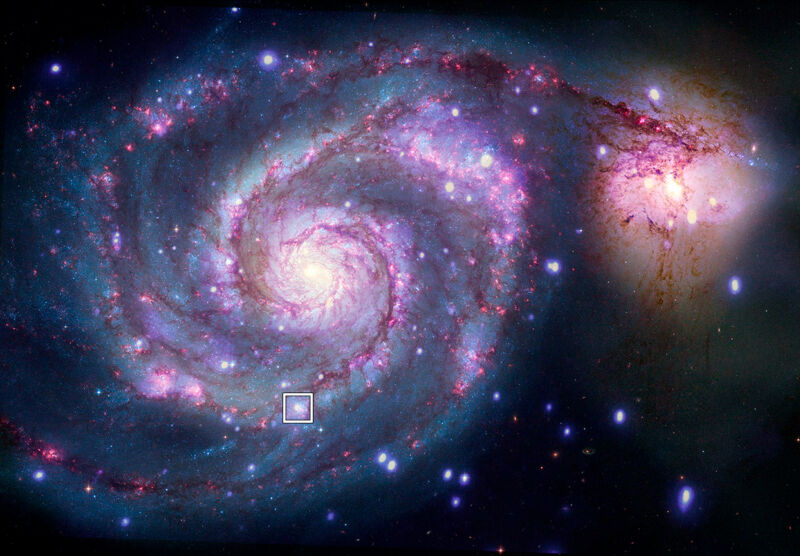

A few years later, Imara and Di Stefano are back as part of a larger team that believes this method seems to work. The data comes from observations of the galaxy M51, also known as the Whirlpool Galaxy. One of the brightest X-ray sources in that galaxy, called M51-ULS-1, is exactly the type of X-ray-emitting binary system that the initial proposal had in mind. The system is composed of an unidentified compact object that appears to be orbiting close to a blue supergiant star. That supergiant seems to be losing matter to the compact body in a way that powers a steady stream of X-rays.

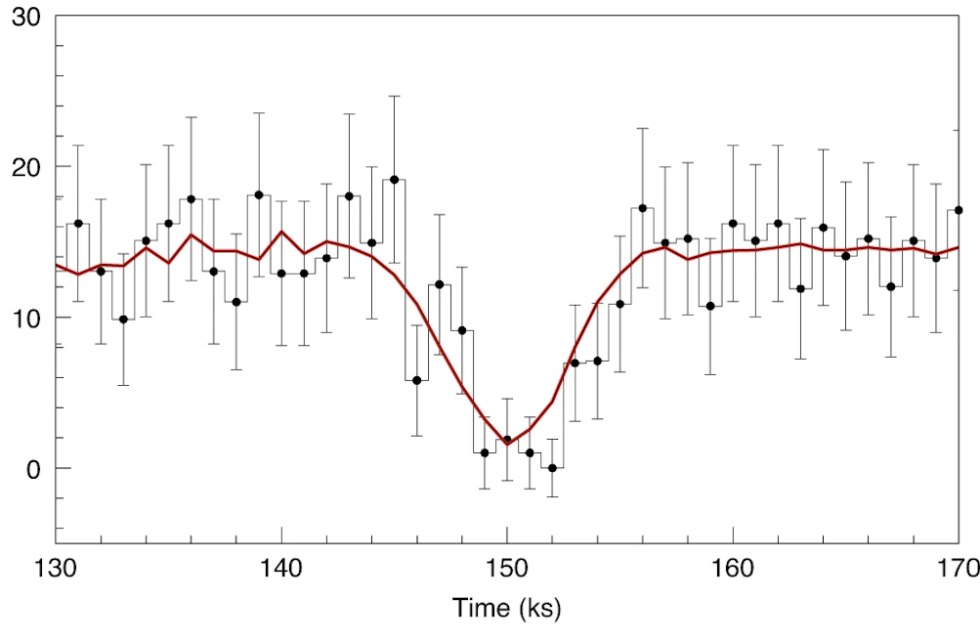

Back in 2012, M51-ULS-1 was in the field of view of the Chandra X-ray Observatory when the x-ray source suddenly went quiet. Before and after the event, Chandra had been detecting an average of about 15 photons per thousand seconds coming from M51-ULS-1. Then there was a sudden decline, and for over a half-hour, absolutely no photons were detected. About a half-hour later, everything was back to normal.

There's often a lot of variability in X-ray sources, since the inflowing material that powers them can vary and even obscure the origin of the X-rays. But those events don't look like what the researchers were seeing. If an X-ray source goes quiet (or comes back on), it usually occurs very gradually, and the intervening matter will tend to block some wavelengths more efficiently than others, leading to a change in the "color" of the light without eliminating it entirely.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.