The 17th century still-life painter Abraham Mignon was known for his depictions of flowers, fruit, forests, and grottoes, among other objects. But over time, certain pigments have degraded to such an extent as to alter the artist's intent. Most notably, a yellow rose prominently featured in Mignon's Still Life with Flowers and a Watch has become flattened and monochrome, particularly compared to the other blooms featured in the painting.

A team of Dutch and Belgian scientists used chemical and optical imaging techniques to examine the elemental distribution of the various pigments, according to a recent paper published in the journal Science Advances. In this way, they could infer Mignon's original painting technique—specifically how the artist built up layers to create what would have been a 3D appearance for the original rose.

According to the authors, over time, artist pigments and binders in oil paintings inevitably deteriorate when exposed to external factors such as light, relative humidity, temperature, and/or exposure to solvents, as well as incompatible pigment mixtures. The result was discoloration and color changes that can affect the paint's structural integrity, causing such defects as loss of transparency, brittleness, or micro-cracks.

Examples of this kind of degradation include the discoloration of a blue glass pigment Rembrandt used in several paintings; the fading of light-sensitive pigments—Prussian blues, organic yellow, and red lake pigments—and the darkening of chrome and cadmium yellow in the works of Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso, among other great artists.

Mignon's yellow rose—a signature flower among 17th century still-life painters, per the authors—has suffered a similar fate. The rose provides "an exemplary topic for this study, looking flat and poor in color contrast while featuring a crumbling powdery appearance or a significantly broken up paint surface," the authors wrote, adding that the rose lost most of its 3D character, particularly when compared to the other, better-preserved flowers in the painting.

To better understand how the rose degraded and to get a better idea of what Mignon originally intended the rose to look like, the team employed a combination of imaging techniques—an approach that prior research has shown to be quite effective. For instance, conservationists have been meticulously restoring Van Eyck's famed Ghent altarpiece housed in Belgium's Saint Bavo's Cathedral. As we reported in 2020, with the help of several advanced imaging techniques, they could identify where overpainting from earlier restorations obscured the original work, revealing previously unknown revisions to the Lamb of God figure in the inner central panel.

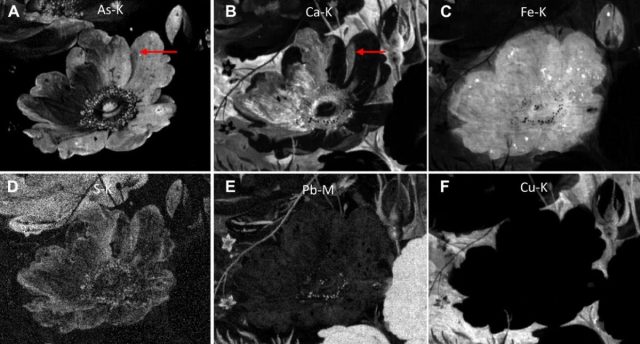

The Dutch and Belgian researchers used macroscopic X-ray fluorescence imaging (MA-XRF), macroscopic X-ray powder diffraction imaging, and reflectance imaging spectroscopy to map the distribution of elements present in Mignon's painted yellow rose, as well as 3D microscopy of the rose's paint surface. That analysis revealed the details of the original brushwork used to create the flower's 3D illusion, which is no longer visible to the naked eye.

Arsenic, calcium, and sulfur mapping, for instance, showed the definition of the flower and hinted at the original illumination achieved through Mignon's use of light and shadow, while the iron distribution showed its overall shape. "While the arsenic map visualizes the light striking the flower with intricate details and highlights that were meticulously applied to define the flower petals and stamens, the distribution of calcium appears to correlate with the expected shadow areas," the authors wrote. "This is particularly visible where one of the upper flower petals cast a shadow on a neighboring petal."

The calcium distribution suggested that Mignon also likely used a translucent pigment known as yellow lake, which is difficult to identify once it has faded. As for the iron distribution map, it suggested a single oval-shaped under-painting applied at an earlier stage to mark the planned position of the flower.

Based on their analysis, the authors concluded that Mignon had employed a three-step method used by many still-life painters from this period. The artist would first block the position of the flower with a monochrome underpainting and then flesh out the details by applying semi-transparent paints such as glazes for the shadows. Contemporary still-life instructions for artists recommended specific pigments (such as yellow lake for reflections) when rendering yellow roses. Mignon seems to have hewed closely to this well-documented process, which explains why the yellow rose degraded more than the other flowers in the painting.

"Both pigment mixtures that were used for creating either the shadows on the flower or the bright yellow highlights degraded or faded, and while these paint layers were intentionally already thinly applied, conforming to the painting technique of still-life painters, both have caused an increased visibility of the underlying, monochrome yellow ocher paint layer, which is now responsible for the overall color appearance of the rose," the authors concluded. "This resulted in a flatter (less 3D)-looking flower as subtle transitions defining the body of the flower can no longer be perceived, which is the reverse optical effect originally intended by Mignon."

DOI: Science Advances, 2022. 10.1126/sciadv.abn6344 (About DOIs).

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.