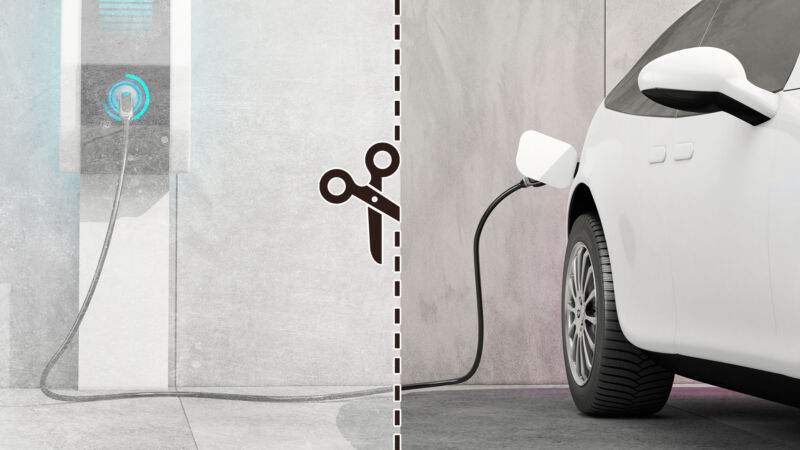

For much of the automobile's existence, speed was the statistic that sold. But the move to electric vehicles is emphasizing range over performance—ironic given the EV's inherent performance advantage here. While range remains a barrier to EV adoption, it takes second place to charging logistics. For about two-thirds of US drivers, the answer is simply to charge at home, parked in a garage or carport. But for the remaining third, that's not possible, and that's a problem.

From the post-war decades, a win at the racetrack or a new speed record translated to showroom success, both in the US and Europe. In turn, horsepower wars between automakers erupted every few years, steadily making our cars quicker and quicker. That trend is arguably accelerating—the near-instant torque of an electric motor means even SUVs that aren't supposed to be that sporty are capable of 0-to-60 times that would rival a supercar not too long ago.

But when every EV can launch from a stoplight fast enough to give you whiplash, pretty soon everyone needs a new reason to one-up each other. The range fixation makes plenty of sense, given the long charging times and the difficulty that would ensue from completely running out of charge while out in the world. But in practice, most of us drive fewer than 30 miles a day, and many EVs fill their days running errands and commuting, returning home to recharge to 100 percent overnight.

That amounts to about 1.6 million homes, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation, and those numbers will increase as building codes are starting to require that new builds—both single- and multifamily—include some provision for EV charging. This is fine and dandy for people moving into new builds, but that still leaves people who street-park in the cold, as well as those of us who live in older multifamily developments with parking lots.

"The biggest headache is electrical upgrades, because many times you've got a client that's waited a long time to make the decision, they've made the decision to invest in charging units, and then it's a nine-month delay waiting for the utility to bring a new transformer and new panels or new switch plates or what have you," said Mark LaNeve, president of Charge Enterprises, an infrastructure company.

"We're dealing with a lot of owners, managers of multi-unit housing, condos, apartments, and it's not only [the electrical delays], but it gets to 'what's the model going to be?' If you have 100 residents, do you put in 10 level two chargers? And then who's paying for it—do all residents pay for it, or just the residents who use it?" LaNeve asked.

Microgrids as the solution?

Indeed, this is a problem I've been dealing with at the 60-year-old, 518-unit co-op I live at in Washington, DC. After making a convincing case for a pair of shared level two chargers, the co-op board approved it, but at least two years have passed with no chargers on-site because our 1962-era electrical panels can't cope with the added power demand. Those panels are in the process of being upgraded, but even then, it will require our power company's OK before moving ahead with adding chargers.

LaNeve thinks microgrids could be the solution, not just for multifamily developments like mine but for businesses or fleets that are electrifying and also need flexible charging capacity. Indeed, Formula E has been doing exactly that for some years now, traveling with its own microgrid that it sets up at each ePrix instead of having to depend on local power infrastructure. These can combine battery storage and wind or solar power as well as wiring and chargers.

"The problem is, they're very expensive upfront. And you could put two level two chargers in—depending on if it's a clean install, between $20,000-$30,000; something like this might be $100,000. Now, over time, it'll pay for itself tenfold. But to get the complex or the business to invest that 100 grand when we only need two chargers right now, it's a hard sell," LaNeve said.

The solution doesn't just lend itself to AC charging; a company called ADS-TEC, which has extensive experience with microgrids, has recently started deploying battery-buffered DC fast chargers called Chargeboxes. Instead of just connecting the DC charger to the grid, the Chargebox uses its electricity feed to trickle-charge a battery pack constantly and uses that stored power to deliver higher charging speeds to EVs than would otherwise be possible—for example, using a 50 kW electrical connection to charge the storage battery, and then discharge that battery into an EV at up to 350 kW.

"The actual costs for installation of a Chargebox is roughly 18 percent lower than the legacy approach to the fast charger," explained ADS-TEC head of global affairs John Tuccillo. "And that's really because you don't have to do all the elements of the utility extension or build up. You're not digging deep holes, you're not digging trenches, you're not buying transformers, you're not buying switchgear, you're not buying cable; you are plugging into the local feed. Now, don't get me wrong, there is some installation requirements like anything else, but it's not anywhere near the scale that's needed for DC fast charging, following the traditional approach," Tuccillo told Ars.

This approach also has the advantage of avoiding extremely expensive demand fees that can result from a fast charger wanting to draw several hundred kW from the grid. And that helps the total cost of ownership of a battery-buffered DC charger beat the total cost of ownership of a conventional charger of similar power output by around 30 percent, although, since it's DC charging we're talking about, that still means around $1 million over a decade.

Somewhat encouragingly, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 contains tax breaks for microgrids, among its many provisions. But wide-scale EV adoption might need more than just government tax breaks if we're going to meaningfully electrify much of our already-built infrastructure.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.