For several years now, NASA has publicly discussed the initial phase of its Artemis Moon program. These first three missions, to be conducted over the next four or five years, are steps toward establishing a human presence on the Moon.

The Artemis I mission should launch later this year, testing NASA's Space Launch System rocket and boosting the Orion spacecraft into lunar orbit. The second mission, Artemis II, will more or less be a repeat, only with four humans on board Orion. Then comes the big test, Artemis III, which will send two humans to the Moon and back during the middle of this decade.

Beyond these missions, however, NASA has been vague about the timing of future Artemis missions to the Moon, even as some members of Congress have pressed for more details. Now, we may know why. Ars Technica has obtained internal planning documents from the space agency showing an Artemis mission schedule and manifest for now through fiscal year 2034.

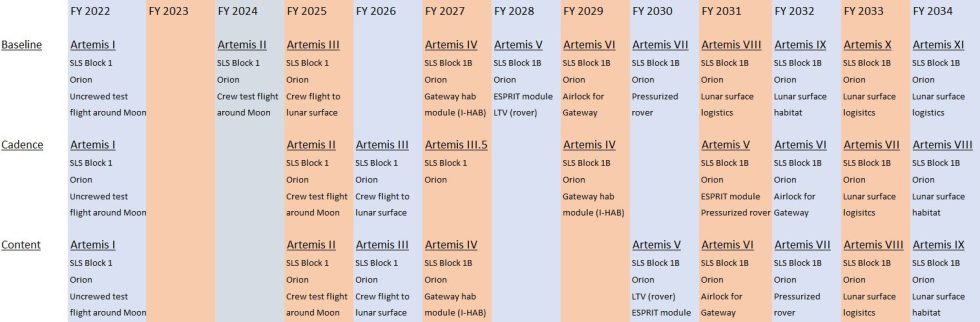

At present NASA has its baseline plan for Artemis, which is shown below. But NASA has also developed at least two "in-guide" schedule options, which agency planners believe are achievable with anticipated budgets, the documents show. These revised schedules indicate that NASA planners do not believe the baseline plan will be achievable on time or within budget.

One of the internal schedules, labeled "cadence," prioritizes launching regularly. The other, labeled "content," prioritizes launching only when the most meaningful payloads are ready. Combined, they reveal that NASA is struggling to cram an ambitious exploration plan into a finite budget. The result is a slow-moving lunar program that, in large part, fails to deliver on the goals of the US National Space Policy.

In response to questions about the internal schedules, NASA spokeswoman Kathryn Hambleton said, "NASA is pressing ahead with its baseline plans for Artemis missions beyond Artemis III. The agency routinely evaluates alternate architectures as a prudent part of programmatic planning."

Although NASA can say it is sticking with the "baseline" plan for Artemis, this notional timeline is almost certainly unattainable. Already, the agency is looking at moving the Artemis III mission beyond 2025 due to a number of factors, including a lack of Moon-ready spacesuits. Moreover, the preparation of revised schedules strongly suggests that NASA is ready for inevitable delays.

Here are some of the key issues raised by the revised schedules, which are reproduced above from the original NASA documents to protect our sources.

- There are huge gaps between missions. To close one three-year gap, NASA is considering the creation of an "Artemis III.5" mission that would require the agency to procure a fourth interim upper stage and delay development of other key programs.

- The slow progression in missions puts off development of a "base camp" on the Moon for years, with the earliest emplacement of a lunar surface habitat not coming until 2034.

- NASA will spend the next 10 years focused on assembling a small space station in lunar orbit, rather than building up capabilities on the Moon's surface.

Cadence vs. content

The schedules show NASA weighing whether to prioritize a regular cadence of missions or more meaningful payloads. Notably, NASA is considering the addition of an "Artemis III.5" mission in the 2027 timeframe to avoid a three-year gap that would otherwise occur. This mission would require a fourth launch of the original version of the Space Launch System rocket, which uses the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage built by United Launch Alliance.

It is likely that this mission would cost about $5 billion and send four astronauts to the small Lunar Gateway, with two going down to the Moon's surface. And there would be other costs. To support the Artemis III.5 mission and evenly distribute the flight gaps, the documents say that NASA would need to delay several Artemis projects, including: Gateway Logistics, both pressurized and unpressurized lunar rovers, a surface habitat, and the Booster Obsolescence and Life Extension program to upgrade the SLS rocket's side-mounted boosters.

Why are there long gaps between missions? One issue is simply financing. With the Artemis Program, NASA is attempting to fit a lot a large, new hardware into a limited budget. Congress has not been overly enthusiastic about funding all of these new programs. The agency also may be concerned that, after launching the core elements of the Lunar Gateway orbital station, additional modules will not be ready to launch until the latter part of the 2020s.

NASA also recognizes that delays are possible with the upgraded version of the Space Launch System rocket, known as Block 1B. This rocket has a more powerful second stage, the "Exploration Upper Stage," which can carry Gateway modules to the Moon along with crew aboard Orion. The new upper stage is far from ready, though, and last week NASA's Inspector General said the massive mobile launch tower used to support it would be years late and substantially over budget. Under the "cadence" schedule proposed by NASA planners, this Block 1B version of the SLS rocket need not be ready until 2029.

Last week, during a press availability, the senior NASA official responsible for these timelines—Jim Free, Associate Administrator for Exploration Systems Development—said the agency is working on "multiple manifests" due to budgets and other factors. He said that, as part of NASA's budgeting process for fiscal year 2024, he is trying to craft a single plan for exploration through at least the Artemis VI mission.

Free also reiterated that it is NASA's goal to reach a cadence of annual launches, which is important because it gets NASA doing more things on and near the Moon, more quickly. It also helps with costs, as there are large fixed costs with the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft, whether or not the vehicles fly during a given year. "Absolutely our goal is to get to that yearly cadence," Free said.

Previously, NASA indicated it would attempt to reach an annual cadence with the Artemis IV mission in 2027. Based upon the revised schedules, such a yearly cadence will now not come before 2030, at least.

Base camp, where?

As part of the formulation of the Artemis Program, the Trump White House updated the "National Space Policy of the United States of America" in 2020. The Biden Administration has largely gone along with these principles, including embracing the Artemis Program.

Among the goals outlined in this document was extending human economic activity in space "by establishing a permanent human presence on the Moon, and, in cooperation with private industry and international partners, develop infrastructure and services that will enable science-driven exploration, space resource utilization, and human missions to Mars."

That same year, NASA outlined its plans for "Lunar Surface Sustainability" in a report to the National Space Council. The intent of all of this was clear: NASA intended to establish a sustained presence on and around the Moon, demonstrating key technologies that would eventually support human missions to Mars. The key elements included a lunar terrain vehicle, a "habitable mobility platform" that would enable crews to take trips across the Moon lasting up to 45 days, and a surface habitat for up to four crew members. This became known as the "Artemis base camp."

NASA's internal schedules, however, put off any real development of such a base camp into the 2030s. Even if NASA manages to send a lunar terrain vehicle before then, functionally it would be little different from the unpressurized electric rover used during the Apollo Moon program five decades ago. In other words, Artemis would feel similar to Apollo, rather than like something new.

Clive Neal, a Notre Dame geologist and prominent scientist pushing for a lunar exploration program, said NASA's internal timeline is so stretched out that it is effectively meaningless. The plan also ignores the US space policy of focusing on developing a permanent presence on the Moon.

"I don’t get it, I just really don’t get it," he said. "Has nobody at NASA read the space policy? It is really quite bizarre. There's nothing sustainable about the approach they're taking."

A focus on Gateway

The internal schedules reveal that NASA is going to spend the entirety of the next decade, if not longer as schedules inevitably slip, building the Lunar Gateway.

The core elements of the Gateway, including its power and propulsion systems as well as a small habitat module, are presently due to launch on SpaceX's Falcon Heavy at the end of 2024. (These elements will have a minimum 15-year lifetime, NASA says.) Then the International Habitation Module (I-HAB) and the European System Providing Refueling, Infrastructure, and Telecommunication (ESPRIT) modules, both provided by the European Space Agency, as well as an airlock would arrive later in the 2020s or early 2030s on Artemis missions.

Such an effort, according to NASA's revised schedules, will require most or all of the capability of the SLS rocket during that time frame, and they could preclude the agency from developing a greater focus on lunar surface activities.

This is also troubling to some scientists like Neal, who still are not sure what purpose the Lunar Gateway serves. The station began nearly a decade ago, and it was created primarily because of the propulsion shortcomings of the Orion spacecraft's service module. In short, combined with the Space Launch System rocket, Orion does not have enough propulsive capability to fly all the way into a low lunar orbit and then return to Earth. So NASA devised the concept of a Lunar Gateway in a higher elliptical orbit. Pragmatically, this was an easy sell. NASA had built the International Space Station already in low-Earth orbit, so it knew how to move on to Gateway.

NASA has fit the Gateway into its Artemis plans, which came afterward. Artemis missions presently call for humans to launch to the Gateway in the Orion spacecraft and dock there. From the Gateway, they will board a lander and go down to the Moon's surface.

The problem with this solution is that, last April, NASA selected SpaceX's Starship to serve as a lunar lander. Starship is already larger than the proposed Gateway, and it replicates many of its power and propulsion capabilities. So if you already have Starship as part of your lunar architecture, and if NASA is really interested in activities on the lunar surface, why spend a decade and tens of billions of dollars building the Gateway?

"I’m sorry, but it's a waste of money," Neal said. "We’re not fulfilling space policy by building an orbital space station around the Moon. We need to be on the Moon for that."

Others disagree. NASA says the Gateway is an essential part of making the Artemis Program "sustainable" and for developing technologies needed for deep space travel beyond the Moon to Mars.

NASA's internal schedules, however, splash cold water on the idea that the Lunar Gateway is sustainable alongside extended surface activities and a base camp. Given the near certainty that there will be more delays, the Artemis Program is probably at least 15 years from having a semi-permanent habitat on the surface of the Moon. That is just about long enough to be "never" in spaceflight terms, and it would push Mars exploration into the 2040s or 2050s.

Something is probably going to have to give if NASA is to get anywhere with Artemis.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.