The Atlantic hurricane season officially ends on Wednesday, bringing to a close the six-month period when the vast majority of tropical activity occurs in the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea.

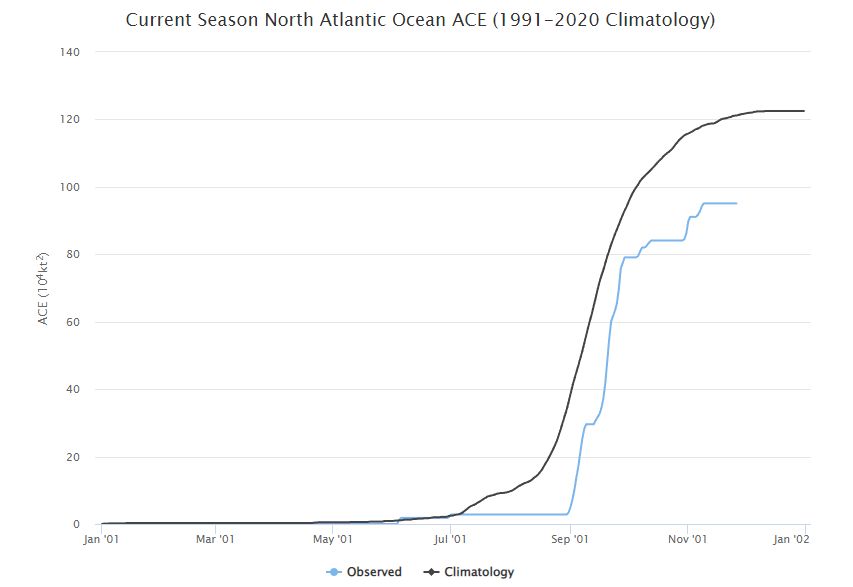

Prior to the season, forecasters generally expected a busier-than-normal season. However, six months later, overall activity this year has come in slightly below normal. One of the more scientifically rigorous measurements of seasonal activity—based on the length and intensity of storms—is accumulated cyclone energy. This year's value, 95, is about three-quarters of the normal value of 126.

That bland statistic belies the fact that this was an odd season. After three weak early-season storms, the Atlantic basin produced zero named storms between July 3 and August 31. This was the first time since 1941 that the Atlantic had no named storm activity during this period. Then, a light came on. Four hurricanes formed in September, along with three more in November. This brought seasonal activity to near-normal levels.

"This season was really bizarre," said Phil Klotzbach, one of the world's foremost seasonal hurricane forecasters. "I’m giving a talk to the American Meteorological Society on Tuesday about the season, and I’m referring to it as the most abnormal 'normal' season on record."

What happened

So what caused this? It's a question that Klotzbach and his research team at Colorado State University have been investigating since the anomalously quiet August. The season's sputtering start was all the more surprising because this is a La Niña year, a pattern that typically leads to lower-than-average wind shear across the Atlantic. This favors increased tropical activity.

In August, however, wind shear was higher than average in the region of the Atlantic Ocean where tropical systems commonly form. These crosswinds at varying altitudes disrupt the circulation of rotating storms, such as tropical storms and hurricanes. Another big factor this August was the incursion of dry air from the mid-latitudes. Dry air, of course, saps the thunderstorms that are essential to forming a tropical cyclone.

The shear and dry air appear to have had their origins in the mid-latitudes, the area between 30 degrees and 60 degrees north of the equator. And this higher wind shear and increased amount of dry air may have been transported southward into the tropical Atlantic Ocean due to a phenomenon called "wave breaking," Klotzbach told Ars.

"I think a lot of the shear and dry air had mid-latitude origins and was associated with vigorous wave breaking," he said. "Wave breaking is associated with upper-level low-pressure systems that have anomalous upper-level westerlies on their southern periphery. These upper-level westerlies increase vertical wind shear. Also, mid-latitude air is typically drier than tropical air, stifling thunderstorm development and effectively choking African easterly waves."

Klotzbach said he has been working with Jhordanne Jones, who graduated from his research group last year and got her Ph.D. studying the predictability of mid-latitude wave breaking. The goal is to better understand the predictability of this phenomenon and incorporate it into seasonal forecasting.

"The predictors that she found did hint at some increased potential for wave breaking this year, but not as much as was anticipated," Klotzbach said. "We’ll certainly be spending more time looking at prediction of wave breaking for our forecasts in the future."

Blowing up

After the quiescent period in August, the Atlantic tropics came alive in September, beginning with the formation of Tropical Storm Danielle on September 1. Five additional storms followed in the next three weeks, with Hurricane Ian being the strongest of them. With maximum sustained winds of 150 mph at landfall along the southwestern coast of Florida, Ian is tied with five other hurricanes for the fifth strongest continental US hurricane landfall on record.

Another surprise came in November when the late-season Hurricane Nicole formed. It eventually made landfall along the southeast coast of Florida as a Category 1 hurricane.

Both of these storms—Ian and Nicole—proved disruptive for NASA and its Artemis I program. Ian's fury forced the space agency to roll the Space Launch System rocket and its Orion spacecraft back into the Vehicle Assembly Building to protect it from the storm in September. Less than two months later, facing another hurricane, NASA opted to remain at the launch pad.

It proved a smart decision, as less than a week later, the Artemis I rocket had safely launched Orion toward the Moon.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.