MILFORD, MICH.—Over the radio, I've been instructed not to drive into the large crater near the south pole of the Moon. I had been circling the crest looking for a way in and as soon as mission control realized what I was about to do, it vetoed my heading. I turned away from the impact site and drove toward a hazy sun off in the distance determined to hit at least 25 km/h while battling the awkward effects of gravity one-sixth that of Earth.

General Motors and its partner Lockheed Martin are building a lunar rover without a NASA contract. They want to fly this vehicle to the Moon in support of the Artemis mission, because we're going back to the Moon to drive and GM wants to be there first.

Another voice comes over the radio. "That's five minutes. Please come to a stop and we'll recenter the rig."

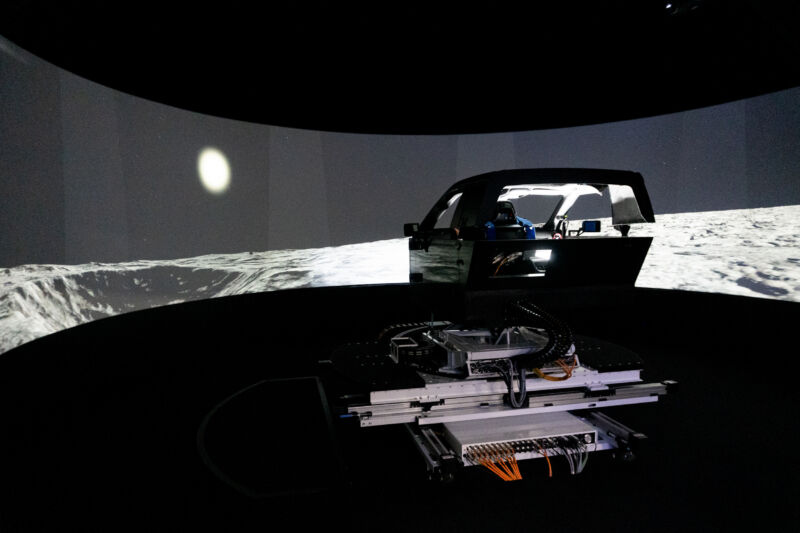

The rig is GM's DIL (Driver in the Loop) simulator in the automaker's Milford proving grounds in Milford, Michigan. The "vehicle" I'm sitting in—while driving on the Moon—has a typical GM interior but with a Corvette steering wheel; likely a nod to the automaker's history of gifting astronauts the sports car. Meanwhile, the projected exterior is a premapped actual location on the Moon, exactly one square kilometer near the south pole of the Moon.

It's a vast wasteland of gray with a diffused sun blazing in the sky. The monochromatic landscape makes it difficult to determine depth. It's not an impossible task, but there are still moments when what seems like a small bump becomes something more substantial as it nears.

Determining whether to hit the space divot head-on or attempt to avoid it comes down to trying to understand and predict the physics of driving on our biggest satellite. With Lockheed's help, GM has programmed the vehicle to drive and react to an environment with one-sixth the gravity of Earth. There's a floating quality to the suspension and ride. With less gravity and zero atmospheric downforce, everything is a potential launch into the air.

According to GM's advanced program lead of vehicle dynamics, the system has a tendency to make people nauseous, as your brain wants everything to react the way it would with Earth's gravity. The simulator's Moon tuning doesn't do what your body is expecting. Hence, a few queasy stomachs and the five-minute time limit. The team at GM has been working up toward hours-long excursions from their five-minute sessions.

In other words, we can't drive all day on the Moon-sim because there would be vomit.

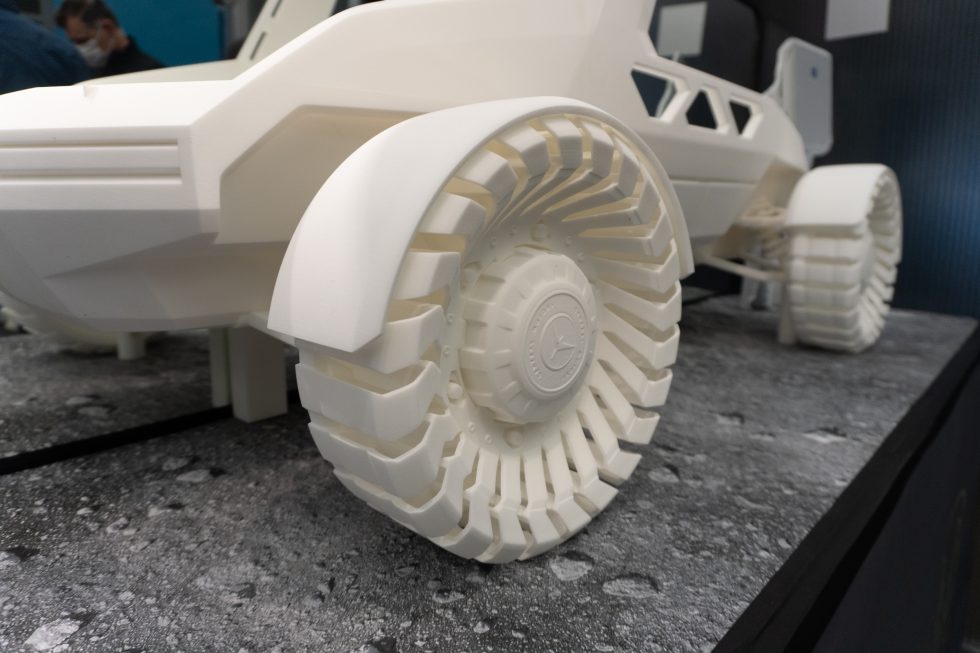

The terrain is an electrostatically charged regolith of metal and glass; a fine dust of asteroid pieces that is like silt that attaches to absolutely everything, and if gets into your electronics can cause some major issues. With Lockheed's help, GM was able to re-create the surface of the Moon and its sharp, menacing dust.

The automaker also spoke to Apollo-era astronauts about their experience in space and on the Moon and what it was like driving the original lunar rover that still sits up there. This information helped tune the suspension but is also key to making sure that getting into and driving the rover is possible. Even simple tasks require some problem-solving ahead of putting a car on the lunar surface.

The astronauts will have limited movement in their suits, so egress needs to take into account the suit and backpack and allow someone to move in a way that doesn't lead to a person hitting or getting caught on controls or the structure. Even seatbelts are a struggle thanks to the thick gloves.

In the simulator, the setup was like that of a normal car. But on the Moon, huge boots could make accelerator and brake control difficult. That may lead to hand controls with gloves that offer haptic feedback. The result is a design that's in a constant state of evolution as the companies determine what will work best for humans on the Moon.

But there's also the autonomous element. The rover will be up there ahead of humans, and the goal is to have a fully autonomous vehicle that can drive around and map the terrain ahead of humankind's return to the Moon.

Brent Deep, chief engineer of GM's lunar mobility vehicle program foresees a future where pre-mapping the area around a future landing site for humans speeds up exploration. Like a robot scout, the rover will explore the area so that once people arrive, they have a game plan on what to explore.

It helps that a day on the Moon lasts 14 (Earth) days of daylight followed by 14 (Earth) days of darkness. So a two-week window driving around with or without people could yield some interesting results not just for NASA, but also for other countries and companies. The lunar mobility vehicle won't just be available to NASA—Lockheed and GM see both commercial and international opportunities. Without a NASA contract, the partnership sees other revenue streams that would help pay for all this research and of course, launching the vehicle into space.

There are limits to what will be available and to whom. A Lockheed spokesperson noted that there are agreements in place for how the Moon is used and of course, monetized. Most importantly, it should be used for peaceful purposes.

Unfortunately, information about battery size, capacity, range, the charge rate, and really most of the things you'd want to know about the lunar mobility vehicle are still under wraps. We do know that it will be charged by solar panels. While some of the public-facing sketches and models have the panels on the side of the vehicle, GM showed off yet-to-be-seen sketches of the evolution of the vehicle with movable panels situated on top.

We do know that it will be based on GM's Ultium battery platform and that the vehicles will have serviceable parts so if it breaks down, it can be fixed on the Moon. It won't be a 400- or 800-volt system, but “something different.” As for a second life for components, GM and Lockheed both noted their focus on sustainability.

The system will support over-the-air updates like an EV on Earth; if there's a battery update that can increase range, it can be sent to the vehicle. Data rates between Earth and the Moon, as well as what will and won't be updated, are still under wraps. Most of the mystery is because there are other companies likely doing the same thing.

It's a new space race to get a vehicle to the Moon, but instead of Cold War rivals, it's companies trying to bring mobility to a large rock orbiting Earth. They're all envisioning a future of multiple vehicles driving around both autonomously and with humans doing research and figuring out how to make money.

But also, making sure astronauts just don't go driving willy-nilly into giant craters.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.