Cost-of-living pressures, a dismal job market and stagnant US federal budgets are leaving lab leaders scrambling to balance the books.

Sharona Gordon can still recall her time as a postdoctoral biophysicist 30 years ago. She was pregnant with her second child, a son, and so it was a fulfilling and exciting chapter in her life. The laboratory she was working in at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle was well funded, and her starting salary was above what was then the average, at US$18,600. Gordon’s husband was a full-time student who also tutored, and they were able to buy a house for their growing family for $130,500, with a mortgage payment of just $600 a month. “Today, my son is a postdoc in the same lab that I was [in], and the average house in Seattle is now 14 times his pay,” she says — his salary started at $53,760. “So obviously things have taken a turn.”

Gordon now runs her own lab in UW’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics. She has four postdoctoral researchers and one PhD student, and worries about how she’ll provide them with an experience to match what she had as an early-career researcher. This includes a competitive salary, given that Seattle’s cost of living is 50% above the national average. Her grant budget from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) hasn’t changed since the early 2000s. “And yet I have to pay part of my salary, as well as the other salaries, all of which have gone up” from that budget, she says. Her lab members’ combined salaries far outstrip the $250,000 annual budget of a typical modular NIH grant, leaving Gordon with less money to fund her research.

Her experience is not unique. Principal investigators (PIs) across the United States are grappling with how best to support their students and staff amid wages that haven’t kept pace with inflation, a dismal job market and stagnant federal budgets. Prompted by a general exodus of early-career researchers to lucrative industry positions, PIs are keen to correct the imbalance but are unsure about how best to do so. In response to strikes, several prominent universities have significantly raised the minimum amounts that postdocs must be paid. Short of securing more funding or successfully lobbying Congress on behalf of higher education, the future of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) is likely to entail smaller labs with fewer staff, even if those who remain ultimately earn a better wage. Not everyone agrees with this outcome, which would put postdoc positions out of reach for many early-career scientists, but PIs say they don’t see another short-term solution to the funding crunch.

“It’s not that we don’t want to welcome more people, we just can’t afford it,” Gordon says, adding that listening to the financial struggles of postdocs at UW has left her feeling ashamed. Even without a ready financial solution, she says, “I can’t see myself going back to paying the low salaries that we’ve been paying.”

State of affairs

Graduate students and postdocs push the scientific enterprise forwards through their day-to-day labour. “Postdocs in particular are the backbone of biomedical research,” says Ankur Jain, a cell biologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, adding that his three postdocs feed into a collaborative lab culture and bring in fresh perspectives and skills. “The subject of salary is close to my heart — I don’t think we can ever compensate them enough.”

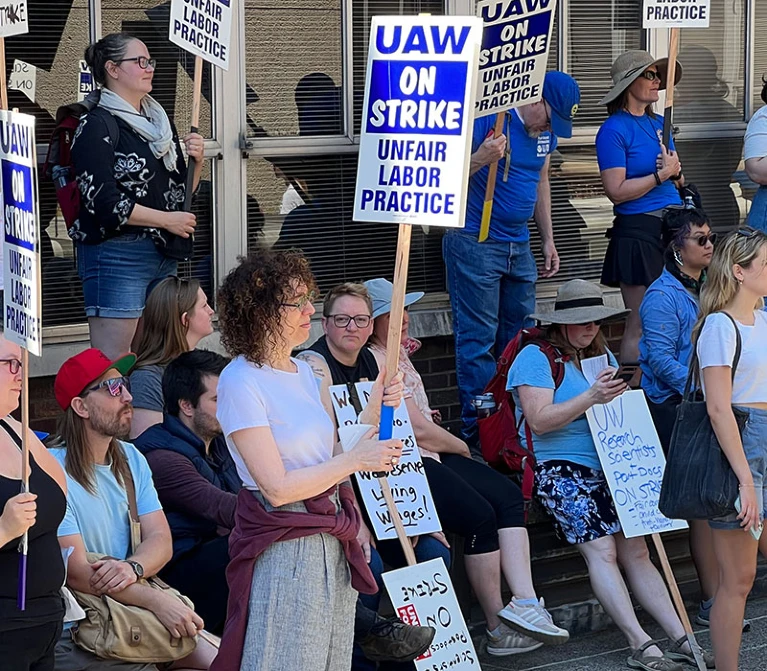

But a series of strikes in higher education has swept across the United States and other countries, amid a reckoning over low pay and poor working conditions. The burgeoning biotech industry now offers US salaries that average $94,000, outstripping early-career academic positions by tens of thousands of dollars.

Scientists have also described challenges in recruiting postdocs in particular, citing long-vacant listings or negotiations that falter. In October, Nature is set to report the results of its second global survey of postdoctoral researchers, revealing the effects of staff shortages and cost-of-living increases since the last survey in 2020. The new survey finds that, for example, nearly two-thirds (62%) of postdocs in North and Central America were dissatisfied with their pay, compared with just 37% of Europe-based postdocs.

Ankur Jain says postdoc salaries are worth it.Credit: Gretchen Ertl/Whitehead Institute

“With postdoc compensation deservedly on the rise, universities will have to adjust to meet new financial demands,” says Thomas Kimbis, chief executive of the US National Postdoctoral Association in Rockville, Maryland.

When postdocs at UW went on strike in June, they argued that the $56,484 annual minimum salary set by the NIH, which is often used as a benchmark, is insufficient. Their new contract establishes a minimum salary of $68,456, set to go into effect in 2024. The 10-campus University of California (UC) system similarly agreed to raise salaries for academic workers by as much as 66% over the next 3 years after 48,000 people walked out in protest. Unlike MIT and Princeton University in New Jersey, both of which agreed to raise their postdoc salaries to $65,000 using temporary ‘bridge funds’ or endowments this year, neither UW nor the UC system have stated where the money will come from. Pay disputes are ongoing between early-career researchers and several UC universities.

One UC PI, who requested anonymity so as not to jeopardize his tenure prospects, says that although he supported the strike, the lack of clear guidance from administrators has left him in a bind. Many graduate students and postdocs receive NIH fellowships or training grants, including three people in his lab, but any supplementary money for the increased UC salary cannot come from the NIH or other federal funds. Instead, PIs must leverage start-up money or charitable funding to make up the difference, or secure a teaching-assistant position for their staff, funded by the university. Close to exhausting his other piecemeal sources of funding, “I’m [at] the point where I’m actively discouraging anyone in my lab from applying for NIH fellowships” so that they can instead take up teaching posts, he says. He acknowledges how incredibly awkward this is, because although winning an NIH fellowship is good for a student’s or postdoc’s career, “I literally can’t afford to have them work in my lab if they do that.”

Asked how PIs should handle this conundrum, NIH acting principal deputy director Tara Schwetz told Nature that paying for one postdoc across more than one grant mechanism is not allowed, owing to the difficulties it would introduce in tracking duplicate spending. She suggested that universities that raised salaries do more to help PIs make up the gaps.

Another solution would be for PIs to pursue extra grants to pay for more students and postdocs, but that prospect is complicated. An R01 (or equivalent) grant from the NIH, which is the usual five-year mechanism that PIs use to fund their labs, can typically support one or two personnel, according to Gordon. “But I’m struggling to keep the funding that I have,” she says, adding that “it’s not realistic or desirable to seek more” grants.

Instead, she writes letters to her senators and has advocated for a stronger federal STEM budget as a member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. She has also started looking for ways to cut back — by attending fewer conferences and fixing her own equipment, for example. “I’m just going to keep my science within the scale that allows me to treat people with humanity,” she says.

Similarly, the anonymous UC PI notes that there has been an obvious increase in demand for the existing pool of NIH investigator grants, forcing him and his colleagues to apply nearly every cycle. He would like to see the UC system put pressure on the California state legislature, which currently provides roughly 10% of UC’s overall budget. “The idea that we don’t ask the state for more money is horrifying to me,” he says, adding that there seems to be little political will on the part of university administrators to bring about change.

Liz Kellogg, a structural biologist who is currently moving her lab from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, says that even if she could secure more funding, “the purchasing power of an NIH grant today is much less” than in the past. “You end up with a mismatch between the money you have to pay people and the science you can actually do with what’s left,” she says.

Show me the money

Funding agencies have started to respond to concerns from students, staff and faculty members. In April, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), a non-profit body that sponsors a series of competitive biomedical research grants, set a new minimum salary of $70,000 per year for almost all of its 300 directly funded postdocs, and urged PIs to use the figure as a benchmark for any postdoc working in their labs. Although the HHMI established a bridge fund to ease the budget burden on PIs, a spokesperson says that the organization has not yet committed to increasing its total grant award budget, although internal discussions are continuing. The US National Science Foundation sets its minimum postdoc salary at $71,099, and salaries scale by area depending on the local cost of living.

At the NIH, the salary picture is more complicated. Last month, the agency rescinded its objection to postdocs and graduate students who work in NIH laboratories unionizing to advocate for better pay and working conditions. (The NIH had previously filed paperwork with the Federal Labor Relations Authority stating that the researchers didn’t qualify as employees.) The NIH also convened a working group last November to address the challenges facing postdocs, including not just compensation, but also benefits, working conditions and protections for international postdocs.

Liz Kellogg (left) with lab members Jung-un Park (centre) and Vinh Truong (right).Credit: St. Jude Children's Research Hospital

Schwetz, the group’s co-chair, says that although the agency has attempted to keep salaries in line with inflation, it has been a challenge. The agency’s budget, when adjusted for inflation, has been relatively static for two decades, and there’s little indication from Congress that it will grow much in 2024. Although the group is considering recommending higher salaries, among many possible solutions, Schwetz says it’s too early to say just how much beyond the current figure of $56,484 a new minimum might go.

In June, the working group released an interim set of guiding principles, calling for fewer — but better-paid — postdocs and a three-year cap on the duration of contracts. It also called for better benefits, professional development opportunities and training for faculty members on how to improve mentoring of their personnel. In December, the group will present a final set of recommendations to the advisory committee to the director.

For Rebecca Bluett, a neuroscience postdoc at UW who participated in bargaining during the strike, a future with fewer postdocs would be a disappointing outcome. “I really hope that’s not what happens,” she says, noting that when resources become even scarcer, they tend not to be distributed equitably. Labs that are flush with funds will be able to hire more postdocs, produce more research and thereby earn even more funding. “I don’t have the answer, but I don’t think that having fewer postdocs is in the public interest or in the interest of scientific progress.”

But others, including Ilana Witten, a neuroscientist at Princeton whose lab includes seven postdocs, says that keeping people moving through the pipeline will not only create fresh opportunities more quickly, but will also minimize the length of time postdocs must live under financial and professional insecurity. “Putting your life on hold financially for that long feels increasingly unsustainable,” she says. “If the changes mean there will be fewer [positions] to increase the salary, then that’s perfectly fine.”

‘Look off the beaten path’

If the NIH does decide to support fewer postdocs but with increased pay, it could change the calculus for many labs across the country. Schwetz acknowledges this, and says that leading a smaller lab will hopefully help PIs to provide a better experience for their team members and to focus on a smaller number of projects. Some scientists are looking forward to that kind of future. Jain currently has 10 people in his lab at MIT, but had 12 for a short period, a situation which, he says, left him with too little time to stay on top of his research and to adequately mentor each individual. On the basis of that experience, he says, reducing the size of labs might spur, rather than dampen, scientific output. “Fewer people may be the solution so that we are intellectually engaged in all the ongoing projects,” he says.

But Kellogg says that slashing her lab’s size feels like a penalty. “I would love to grow, but now I’m looking at having to bring in a lot more grant money just to keep my lab the same size,” she says. She’s moving to St. Jude in Memphis in part because it gives group leaders extra funding to supplement the salaries of students and staff in its research labs. St. Jude recently raised its minimum postdoc salary from $55,349 to $70,013 per year. (It also provides a professional-development stipend of $2,500 per year and access to a career coach.) Freeing herself from relentless grant-chasing “will allow me to do the best science I’m capable of doing,” she adds.

The vast majority of students and postdocs in the United States applying to universities in states such California, New York and Massachusetts might do well to consider other, less expensive parts of the country, according to Mark Rebeiz, a developmental evolutionary biologist at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. “There is this idea that if you’re not doing a PhD or postdoc in a big, coastal city, your future prospects are less,” he says. But many of his PhD students have benefited from Pittsburgh’s lower cost of living, the close-knit, collaborative department and a university that provides good social support (graduate students and postdocs receive the same benefits as faculty members). Many have then moved on to a postdoc at another well-respected university. “Take a look off the beaten path, and you might be very pleasantly surprised,” Rebeiz says.

Adriana Romero-Olivares, a fungal microbiologist at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, has started recruiting new PhD students and her first postdocs, because her university is shifting in 2025 from an ‘R2’-designated university to an ‘R1’, with more-competitive research programmes.

(These classifications, managed by the American Council on Education in Washington DC, are used, among other things, to assess the research output of doctorate-granting US institutions.) As such, the university’s vice-president of research has offered a supplement to cover half of any incoming postdoc’s salary — a welcome boon for early-career researchers such as Romero-Olivares. Without the supplement, “there is no way that I could afford paying for postdocs, with their higher salary”, she says.

Regardless of the actual solution to the problem of funding higher salaries, all group leaders interviewed agreed that postdocs are invaluable members of the academic ecosystem, and that their exodus signals that something is fundamentally wrong with the system as it stands. “We’re looking at a bleak future if we can’t bring in that talented younger generation to further research,” says the PI at UC. “And it’s a shame that it’s simply down to choices about allocating funds.”

Nature 621, 431-433 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02848-3

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.