This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Virginia, Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana have the most to gain in jobs and new investment if PJM, the country’s largest grid operator, can fix some of the problems now leading to long delays in clean energy projects, a new report says.

To make that happen, PJM would need to approve projects at the same rate it did about a decade ago.

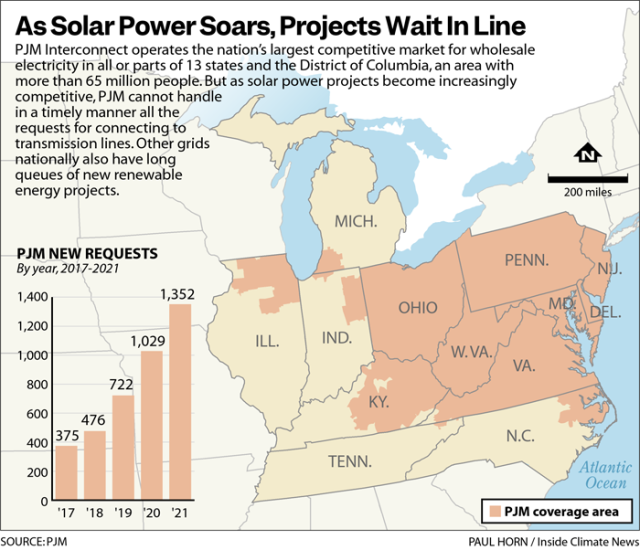

But that requires clearing two big hurdles. The grid operator needs to make major progress on roughly 3,000 active matters in its new service request queue, where 97 percent of more than 250 gigawatts of proposed new generation is for renewable energy, battery storage or a combination of the two. And PJM, whose territory runs from Chicago to New Jersey, would need to add enough interstate power line capacity to connect those projects to the grid.

The June 28 report from the American Council on Renewable Energy (ACORE), a trade group, focuses on roughly 2,000 projects totaling 167 gigawatts of proposed land-based clean energy generation, which PJM is due to process as it implements reforms approved by federal regulators in November. Those reforms include a switch to prioritizing the projects that are the most ready to be built and a “fast lane” for smaller projects, among others.

Report author Noah Strand at ACORE and other contributors acknowledge that not all those projects will ultimately be approved and built. So, the report assumes a completion rate of 20.3 percent, which is comparable to that for 2011 to 2016. It then makes estimates for job creation, investments and other benefits for the resulting 34 gigawatts of clean energy.

With more than 43,000 megawatts of proposed capacity in the PJM queue awaiting approval, Virginia stands to gain roughly a quarter of the $33 billion in capital investment and 198,716 job-years those projects, totaling 34 gigawatts, could provide, the report estimated.

A job-year represents one job for one year. Because each project’s largest employment demands come during the construction phase, that’s a fair way of estimating job creation, said Brendan Casey, who contributed to the report and is deputy director for economic analysis for the American Clean Power Association.

A good rule of thumb for estimating permanent jobs is to divide the total job-years by three or four, he said.

Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana rank second, third, and fourth in potential benefits for proposed projects. Each state stands to gain between $4.7 billion and $5.5 billion in capital investments and roughly 29,000 to 32,000 in job-years, with other states in the grid footprint gaining smaller amounts of investments and jobs.

Additional grid-wide benefits would include an estimated reduction in wholesale electricity costs of more than $16 per megawatt-hour from 2021 levels, due to an increase in renewable energy on the grid and incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act, the report said, citing a December 2022 analysis by Princeton University researchers. Displaced coal generation could also provide substantial public health benefits, valued at roughly $44 per megawatt-hour, the report said.

Multiple factors contributed to the backlog at PJM, including a dramatic increase in interconnection applications as technological advances and market forces drove the clean energy transition forward. But an outdated first-come, first-served, one-project-at-a-time review process slowed progress down. If one project dropped out, for example, it would trigger additional studies and more delays for other projects still in the queue.

Some projects have been in the PJM queue for seven years or more. The new approach approved by federal regulators will use a first-ready, first-served approach, permit reviews of some projects in clusters and allow fast-track processing for some smaller projects.

Of course, any new generation will need somewhere to plug into the power system. Generally, that has called for making improvements to the existing connection points. And PJM’s practice has been to require applicants to bear those upgrade costs.

Average interconnection costs for renewable projects in PJM’s territory increased eightfold from 2017 to 2022, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory reported earlier this year. And “renewables paid disproportionately high connection costs relative to natural gas,” Strand said. The Berkeley Lab report noted that average interconnection costs for wind, solar and storage run five to 14 times more than natural gas plants’ average costs of $24 per kilowatt.

Those higher costs were often due to broader network upgrades, “suggesting that new renewable generation was getting assigned the cost of upgrades that benefited others on the system,” the ACORE report said. And because the price tag for required upgrades often isn’t known until the end of the review process, some projects were no longer commercially viable.

“The development of new transmission is key,” Strand said. Among other things, the new research recommends proactive transmission upgrades by PJM, especially high-voltage transmission lines that will be able to handle more intermittent resources coming onto the grid. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission should also make the cost-allocation process more equitable for clean energy resources, the report said.

PJM had received heavy criticism for the grid backlog, but in its view, “the queue is not the current issue,” said spokesperson Susan Buehler. As the transition to the new processes moves ahead, “PJM has invested significantly in tools and automation, as well as in staffing both in employees and outside contractors.”

Also, she added, “44,000 megawatts of mostly renewable generation resources have cleared the PJM study process but have yet to be built” for reasons such as supply chain, siting, regulatory issues or financing.

Outside observers are focusing on next steps rather than what’s gone wrong in the past.

“It’s easy, I think, to point fingers,” said Katie Siegner, manager of the Rocky Mountain Institute’s carbon-free electricity practice, who did not work on the report. But none of the grid connection problem is easy to solve. “Developers have a hard job, and PJM has a hard job. If this were an easy fix, we wouldn’t find ourselves in the situation we find ourselves in,” Siegner said.

Adding new transmission is probably the biggest hurdle, said Rob Gramlich, founder and president of Grid Strategies, Inc., who also did not work on the report. Nor are interconnection challenges limited to PJM. “Every regional planning entity needs to get ahead of that,” he said.

“FERC has the beginnings of a process on interregional planning,” which can help cope with severe weather from climate change, Gramlich said. But regional transmission operators “really have to get busy on long-term transmission planning. There’s just no way around that.”

In other words, no matter how quickly PJM or any other grid operator moves through its queue, new generation needs somewhere to go. Gramlich compared it to having lots of meals ready at a fast-food restaurant.

“If there’s only one cash register, it’s going to be a problem. If you open up more cash registers and everyone can go to multiple cashiers, everything will go more smoothly,” he said.

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.