Once upon a time, during the Cretaceous period, a tiny crab wandered out of the water onto land and somehow got trapped in amber, which preserved it for 100 million years. At least that's what a team of scientists hypothesize might have happened in a new paper announcing their discovery of the oldest known modern-looking crab yet found in the fossil record. The paper was published in the journal Science Advances.

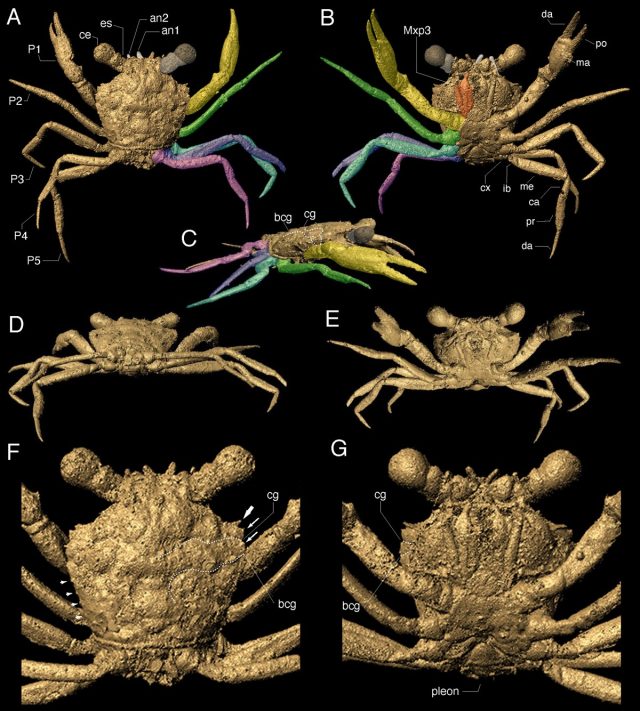

This new type of "true crab" (aka a brachyuran) measures just five millimeters in leg span and has been dubbed Cretapsara athanata. The name is meant to honor the period in which the crab lived and Apsara, a South and Southeast Asian spirit of the clouds and waters. "Athanatos" means "immortal," a sly reference to the fossilized crab being frozen in time.

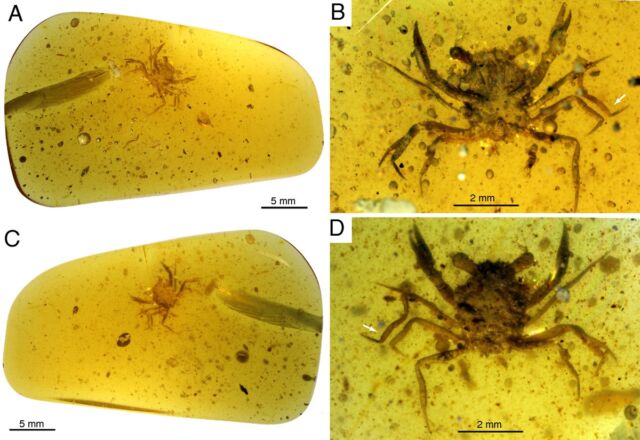

It's rare to find nonmarine crab fossils from this era trapped in amber; most such amber fossils are those of insects. And the previously discovered crabby fossils are incomplete, usually consisting of pieces of claws. This latest find is so complete that it doesn't seem to be missing even a single hair. The find is of particular interest because it pushes back the time frame for when nonmarine crabs crawled onto land by 25 to 50 million years—consistent with long-standing theories on the genetic history of crabs—and offers new insight into the so-called Cretaceous Crab Revolution, when crabs diversified worldwide.

“If we were to reconstruct the crab tree of life—putting together a genealogical family tree—and do some molecular DNA analysis, the prediction is that nonmarine crabs split from their marine ancestors more than 125 million years ago,” said co-author Javier Luque, a postdoc in evolutionary biology at Harvard University. “But there’s a problem because the actual fossil record—the one that we can touch—is way young, at 75 to 50 million years old. So this new fossil and its mid-Cretaceous age allows us to bridge the gap between the predicted molecular divergence and the actual fossil record of crabs.”

The amber in which this crab was found is part of the collection at the Longyin Amber Museum in China. The museum purchased it in 2015 from local miners in Myanmar. (The paper includes the authors' assurances that their research has been limited to items predating 2017, when hostilities resumed in the country.) Luque, who has been studying the evolution of crabs for over ten years, heard about the specimen and became "obsessed" with it.

Thus began an international collaboration that includes researchers from Harvard, the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Yale University, the University of Alberta, UC Berkeley, Yunnan University, and the Royal Saskatchewan Museum. Co-author Lida Xing of the China University led the team that took micro-CT scans of the fossil to reconstruct a 3D model. The reconstruction is so finely detailed, it enabled the scientists to observe not just the crab's body but also soft tissues like the antennas, large compound eyes, and mouthparts—including the fine hairs lining those parts.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.