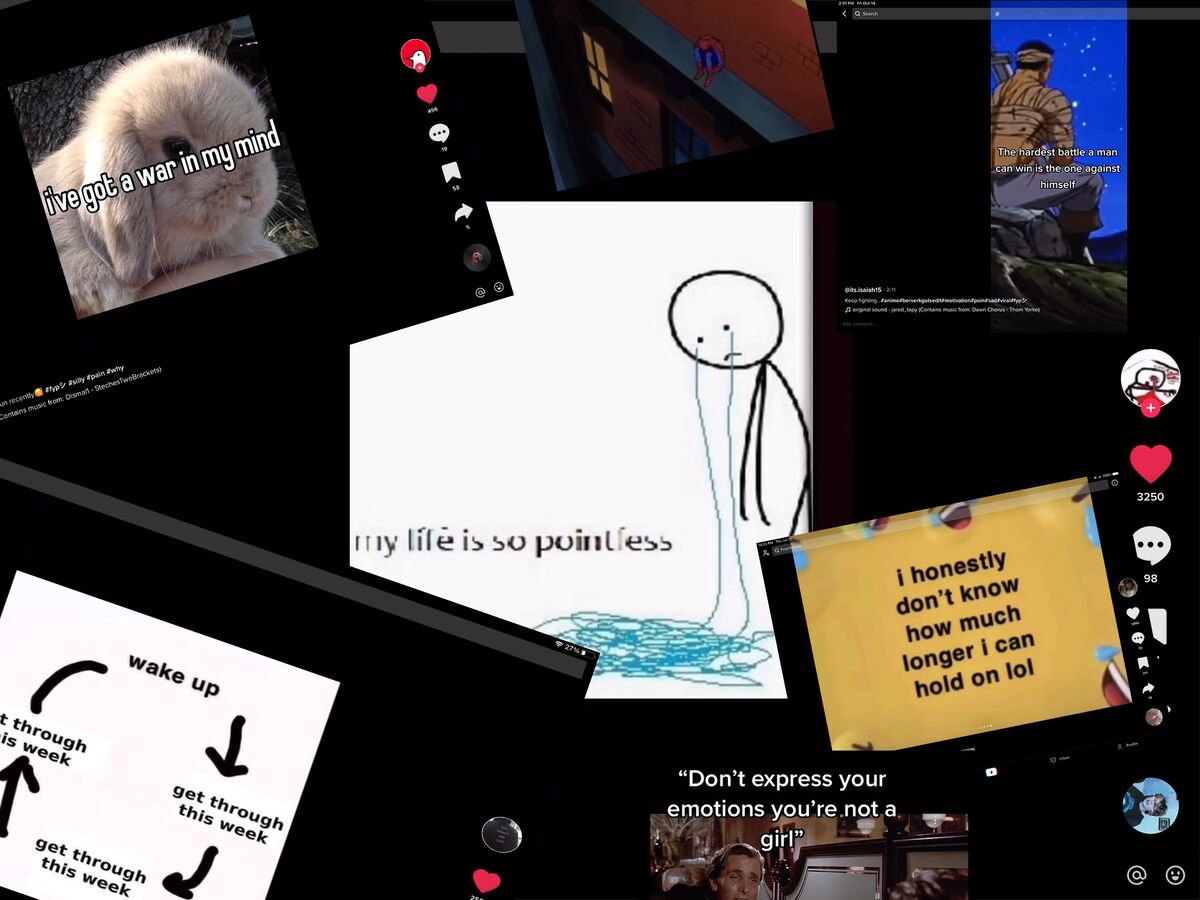

The superpopular app can serve up a stream of anxiety and despair to teens. TikTok says it’s making improvements but now faces a flood of lawsuits after multiple deaths.

TikTok’s algorithm doesn’t know Chase Nasca is dead.

More than a year after Nasca killed himself at age 16, his account remains active. Scroll through his For You feed, and you see an endless stream of clips about unrequited love, hopelessness, pain and what many posts glorify as the ultimate escape: suicide.

“Take the pain away. Death is a gift,” says one video pushed to the account this February, days before the first anniversary of Nasca’s death. In another, a male voice says, “I’m going to put a shotgun in my mouth and blow the brains out the back of my head,” and a female voice responds: “Cool.”

The feed looked much the same in the days before Nasca died. On Feb. 13, 2022, it surfaced a video of an oncoming train with the caption “went for a quick lil walk to clear my head.” Five days later, Nasca stopped at the Long Island Rail Road tracks that run through the hamlet of Bayport, New York, about half a mile from his house. He leaned his bike against a fence and stepped onto the track, at a blind curve his parents had warned him about since he was old enough to walk. He sent a message to a friend: “I’m sorry. I can’t take it anymore.” A train rounded the bend, and he was gone.

It’s impossible to know why Nasca ended his life. There are often multiple factors leading to suicide, and he left no note. But two weeks after his death, his mother, Michelle, started searching his social media accounts, desperate for answers. When she opened the TikTok app on his iPad, she found a library of more than 3,000 videos her son had bookmarked, liked, saved or tagged as a favorite. She could see the terms he’d searched for: Batman, basketball, weightlifting, motivational speeches. And she could see what the algorithm had brought him: many videos about depression, hopelessness and death.

Michelle and Dean Nasca at home with a photo of Chase.

Photographer: Kylie Corwin for Bloomberg Businessweek

Since TikTok exploded into popular culture in 2018, people have been trying to understand the short-form video platform and its impact on kids. Owned by Chinese internet company ByteDance Ltd., the app reached 1 billion downloads faster than any previous social media product. Its success stems from its stickiness. The algorithm underlying its recommendation engine delivers a carousel of riveting user-created content to keep people staring at their screens. TikTok has become so popular—used by 150 million Americans according to the company—that Silicon Valley rivals are trying to mimic it. And politicians are stoking fears that it could be used as a disinformation tool by the Chinese government. In March, the Biden administration threatened to ban the app—something the Trump administration also threatened to do—if ByteDance doesn’t sell its stake.

As the political debate carries on, researchers and child psychologists are watching with increasing alarm. Surveys of teens have revealed a correlation between social media and depression, self-harm and suicide. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show nearly 1 in 4 teens said they’d seriously considered killing themselves in 2021, nearly double the level a decade earlier. The American Psychological Association and other authorities pin the blame partly on social media.

At a congressional hearing in March, a representative brought up Nasca’s death, showing TikTok Chief Executive Officer Shou Chew some of the clips the app had sent the boy and asking if Chew would let his own children watch such content. That same month, Nasca’s parents filed a wrongful death lawsuit in New York state court against TikTok, ByteDance and the railroad.

Picture frame from the Nasca family home, showing school photos of Chase.

Photographer: Kylie Corwin for Bloomberg Businessweek

TikTok says it can’t comment on pending litigation, but a spokeswoman, Jamie Favazza, says the company is committed to the safety and well-being of its users, especially teens. “Our hearts break for any family that experiences a tragic loss,” she says. “We strive to provide a positive and enriching experience and will continue our significant investment in safeguarding our platform.”

TikTok’s original recommendation algorithm was designed by a team of engineers in China, working for ByteDance. But while the app was made in China, it’s used most everywhere except China. It can’t even be downloaded in its homeland. TikTok says its algorithm is now maintained by engineers around the world, with teams based in North America, Europe and Asia contributing. But more than a dozen former employees from the company’s trust and safety team who were interviewed by Bloomberg Businessweek say executives and engineers in Beijing still hold the keys.

Trust and safety designs features and policies to keep TikTok users safe. The team, which is based in the US, Ireland and Singapore, moderates the billions of videos uploaded to the platform every day and is responsible for safety issues such as content that sexualizes minors and viral challenges that encourage kids to take part in dangerous dares. Team members remove posts that violate standards and create tools to help users filter out harmful material. But the former employees, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they signed nondisclosure agreements, say that they had little influence over the algorithm that drives the For You feed and that their requests for information about how it works were often ignored. They insist that they were set up to fail—asked to enhance the safety of an app whose underpinnings they couldn’t comprehend.

TikTok said in 2021 that it was testing ways to prevent its algorithm from sending multiple videos about topics like extreme dieting or sadness. But it didn’t announce any changes until this year, after Businessweek made inquiries and before Chew was grilled by Congress. The company said in a press release on March 16 that it had made 15 system updates in the past year, including breaking up repetitive themes within a set of recommended videos.

Screen recordings of Nasca’s account from April show that, at least in some cases, these efforts have fallen short. “I don’t understand why they keep sending him this stuff,” Michelle says. Every time she opens the account, she finds a steady stream of videos about depression, breakups, death and suicide.

She still recalls exactly what the first video she saw after gaining access to her son’s account said: “I’m caught in a life I didn’t ask to be in.” She watched Chase’s For You feed for more than an hour and couldn’t understand why there were no happy or funny videos, which is what she thought TikTok was about. She asked one of Chase’s two older brothers why he’d made his account so dark.

“Chase didn’t do that, Mom,” her son replied. “That’s coming from the algorithm.”

In a world of infinite information, algorithms are rules written into software that help sort out what might be meaningful to a user and what might not. TikTok’s algorithm is trained to track every swipe, like, comment, rewatch and follow and to use that information to select content to keep people engaged. Greater engagement, in turn, increases advertising revenue. The company has fine-tuned its recommendation system to such a degree that users sometimes speculate the app is reading their minds.

Other social media platforms employ similar recommendation engines. TikTok’s is distinguished by its reach, according to Guillaume Chaslot, a French data scientist who worked on YouTube’s algorithm and now consults with his country’s government on its efforts to regulate online platforms. His experience in the field suggests to him that TikTok’s algorithm controls a greater share of the content reaching a user’s feed than most other social media platforms’ do. And “when depressive content is good for engagement, it is actively promoted by the algorithm,” he says.

Concerns about TikTok’s recommendation engine have been raised internally since at least 2020. That’s when Charles Bahr, a former ad sales manager in TikTok’s office in Germany, says he warned his superiors the algorithm was sending Generation Z users endless streams of depressing and suicide-glorifying videos. Bahr spent a year and a half with the company, joining in July 2020, at age 18. He’d founded two tech startups as a teenager and was advising politicians and businesses on how to master TikTok when he was hired.

When he first started using the app, he says, his For You feed was amusing and fun. He loved the product and was proud to wear his TikTok T-shirt. Once he started posting videos identifying himself as an employee, though, many in his growing following began to forward him disturbing videos that violated TikTok’s rules, urging him to remove them. One of the first scary videos he remembers being sent was of a man shooting himself in the head. As Bahr watched clips like this, sometimes passing them to the trust and safety team for help, his feed began to warp. “More and more depression, suicide and self-harm content came on,” he says. Some days it led him to cry.

Bahr’s feed made selling ads tricky. He regularly held workshops with prospective clients, and many asked to see how the app worked. He couldn’t show his own For You page, he says, because he feared it would scare them off. “Every time I entered a workshop, I switched from my sad, dark account to a second demo account that had quite a normal feed,” he says. “It took me a long time to realize that maybe it’s not only me that has a feed that’s so extreme.”

When Bahr was invited to speak at an annual meeting of TikTok’s European communications team in November 2020, he saw it as an opportunity to raise the issue. In a PowerPoint presentation reviewed by Businessweek, he told the group that TikTok should make it a mission to listen to its users, especially those struggling with mental health issues. “Even though we inspire young people to be their most creative selves on TikTok, there is an endless community of young people not knowing where to go,” one of his slides said. He then showed three posts from young users struggling with depression. Bahr says he recommended that the app not censor such content but instead elevate more positive clips for younger users.

Seven months later, the Wall Street Journal published an investigation that had involved monitoring more than 100 automated accounts to track how TikTok’s algorithm works. Within 36 minutes, the newspaper reported, a bot programmed to engage with videos about depression was fed a stream of content that was 93% about sad topics. TikTok said at the time that the Journal’s bots were not representative of human behavior.

The Journal’s experiment prompted Bahr to conduct one of his own. He opened a new TikTok account and made a screen recording of himself as he engaged with sad content to see how long it would take for his feed to become negative. It took 17 minutes.

Bahr says he raised his concerns on an internal messaging system with the algorithm strategy team in Europe but got no response. A few months later he was fired for alleged expense account fraud and misuse of company tools. Bahr, who maintains his innocence, sued the company for wrongful dismissal. TikTok didn’t pursue its claims against Bahr and settled out of court. The company didn’t respond to requests for comment about Bahr’s 2020 presentation and said it couldn’t respond to his general criticisms or to the concerns he raised internally, which it said it “can’t validate.”

While practically all tech companies are secretive about their data, insiders who also had experience working for Google, Meta and Twitter cast TikTok as Fort Knox by comparison

The pandemic intensified the debate over the impact of algorithmic design on children, as parents worried about the isolation and anxiety brought on by lockdowns, school closures and increased social media use. In December 2021, US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy published a safety advisory about a looming youth mental health crisis, saying rising rates of hopelessness and suicidal thoughts among teens could be linked to both Covid-19 confinement and social media. Too many young people, he said, were being told on these platforms that they weren’t “good looking enough, popular enough, smart enough or rich enough.” He called for social media companies to design their algorithms in ways that would strengthen youth mental health, rather than weaken it.

Psychologists say it’s more difficult for teens to withstand the addictive properties of algorithms, because their prefrontal cortexes, responsible for decision-making, judgment and impulse control, aren’t fully developed. Two-thirds of American teens use TikTok every day, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey, with 16% saying they’re on the platform almost constantly. A significant majority of those surveyed said that they had a positive experience on social media in general and that it gave them a sense of belonging. But almost half said they felt overwhelmed by the drama they found there, and more than a quarter said social media made them feel worse about their lives.

Social media is a fiercely competitive industry, dependent on a young and fickle audience. Companies rely on algorithms to keep their platforms cool in the eyes of teen users, and they protect this intellectual property fiercely. The lack of transparency has limited academic research and given rise to conflicting claims. On one hand, the platforms provide crucial opportunities for connection among teens. On the other, they encourage kids to compare themselves to others, to become addicted to the technology and to discover content that glamorizes harmful behavior.

ByteDance headquarters in Beijing.

Photographer: Greg Baker/Getty Images

Former members of TikTok’s trust and safety team say they feared their platform was having a negative impact on teens and didn’t understand why the company wasn’t hiring child psychologists to work on algorithm design. Many read the documents leaked in 2021 by Frances Haugen, then a data scientist at Facebook, which showed the company was aware its products were harming children. The former TikTok employees say they believed their app’s harms could be worse than Facebook’s but didn’t have the power to address the problem, or even to study it.

While practically all tech companies are secretive about their data, these insiders, who also had experience working for Google, Meta Platforms and Twitter, cast TikTok as Fort Knox by comparison. The secrecy was especially pronounced when it came to the algorithm. Former trust and safety members say that they were never privy to information about how it worked, how it was weighted and how it could be changed and that team leaders couldn’t get answers from the engineers who designed it. More than a dozen people, some of whom were still with TikTok as recently as last year, say they were stonewalled when they tried to access basic information about the algorithm. One safety leader in Europe says he asked the Beijing-based head of engineering to host a meeting with the broader trust and safety team so they could ask questions and better understand the recommendation engine. The leader says the request was ignored.

Several trust and safety workers say that some documents were written in Mandarin and that translations often didn’t include appendixes or links to original data sets, which made it hard to contextualize and analyze information effectively. Five former team members say they quit because secrecy prevented them from doing their job.

TikTok says that it takes concerns voiced by employees seriously, that members of the trust and safety team work directly with engineering and that anyone who left the company before 2021 wouldn’t be familiar with changes made since then. It also says that all important documents about algorithm changes and most important commentary accompanying its code are written in English, but that some notes in the code can contain other languages used by its engineers in Asia and elsewhere.

All social media platforms have been criticized for pumping addictive content to teens, for harming their mental health and for surreptitiously gathering data on them. But when a Chinese-owned company does these things, US lawmakers tend to paint it in a particularly sinister light.

Fears that China’s government could require TikTok to hand over its user data or to have the app’s recommendation engine favor Chinese interests have prompted the EU and the US, Canada and other countries to ban the app from government-issued devices. Some US college campuses have blocked it from their Wi-Fi networks, and in April, Montana’s legislature became the first to pass a bill blocking the app on all personal devices.

Chew testifying before Congress in March.

Photographer: Al Drago/Bloomberg

At the March congressional hearing, Chew, the CEO, was hammered with questions about TikTok’s connection to Beijing and its relationship with the Chinese Communist Party. His attempts to parry the blows—“This is American data on American soil by an American company overseen by American personnel”—were received skeptically.

At one point, Florida Republican Gus Bilirakis introduced Chase Nasca’s parents, who were in the audience. “Mr. Chew, your company destroyed their lives,” Bilirakis said. “Would you share this content with your two children?” He then played a 30-second screen recording from Nasca’s TikTok account, after which he asked Chew whether he took responsibility for the app’s algorithm, yes or no. Chew started to answer, but Bilirakis cut him off. “Yes or no?” he demanded.

“We do provide resources for anyone who types in anything like suicide,” Chew said before Bilirakis interrupted again, declaring, “I see you’re not willing to answer the question or take any responsibility for your parent company, the technology and the harm it creates.”

One of the themes raised at the hearing was also a topic of interest for trust and safety: why TikTok couldn’t change its algorithm to be more like that of its sister platform, Douyin, which operates only in China and shares some of the same source code. Douyin’s algorithm is known to send teens positive content, such as educational posts about science experiments and museum exhibits. It also has a mandatory time limit of 40 minutes a day for children under 14.

TikTok didn’t respond to questions about what share of its app’s source code overlaps with Douyin’s; it did say Douyin is a “separate app governed by different regulatory policies and markets.” It also says it’s been working in recent months to remove some of the mystery around TikTok and updating the platform to make it safer for kids. In 2020 it made it possible for parents to check on what their children are doing while using TikTok. The following year it added stronger privacy measures on accounts of those under 16, setting them to private by default. Then, in February, it announced it would grant US researchers access to some data on accounts and content, though it requires them to send their findings to TikTok before publication. In March the company added a feature that notifies users under 18 when they’ve been on the platform for more than an hour and makes them enter a passcode to remain signed in. It also began allowing users to reset their For You recommendations as though they’d just signed up for a new account if they felt like the content they were seeing was too dark.

Ryn Linthicum, head of mental health policy at TikTok, says that the company forbids posts glorifying subjects like suicide and self-harm and that it trains its artificial intelligence systems and 40,000 human moderators to remove them. In the last quarter of 2022, according to company data, TikTok filtered out more than 97% of such content before other users saw it, among the more than 85 million videos it took down overall.

Moderation is an ongoing challenge, says Linthicum, who uses the pronoun “they” and has been in their role for a year. It’s hard to train an algorithm to distinguish between crying from sadness and crying from joy, or between a video that raises awareness of depression or anorexia and one that encourages those conditions. “This is an incredibly complex space,” Linthicum says. “What may be harmful or hurtful to one person is not necessarily what is going to be harmful or hurtful to another.”

In their view, some content shouldn’t be censored, because it can help vulnerable teens feel less stigmatized. “People go through ups and downs,” Linthicum says. “They have sad life experiences.”

“You could have a child and a parent in the same room, together watching TikTok on their phones, and they’d be seeing an entirely different product”

Videos of people saying they don’t want to live found their way into Nasca’s For You feed in late 2021, according to one of his friends, Brandon Maffei. Now a 17-year-old senior at Bayport-Blue Point High School, Maffei met Nasca in third grade. He was the new kid in school, and he gravitated toward Nasca, who was friendly, free-spirited and funny. When the pandemic shut their school, they, like many American teens, began spending more time on TikTok, sending each other silly videos late into the night. Toward the end of 2021, Maffei noticed that the ones Nasca shared were getting darker. One Nasca sent a few weeks before he died was about suicide. “I opened it up, and I was just like, ‘Damn. I don’t know why he’s sending this to me,’ ” Maffei says. He remembers the video clearly, because it made him cry. The music was depressing, and the on-screen caption read: “It’s not worth it anymore.”

Maffei started telling people, including Nasca, that the app showed too much distressing content and he wanted to delete it. “It’s really bad for mental health, because it pushes those sad depressing feelings onto you, even though you don’t feel them,” he says.

In February, Businessweek sent a nine-minute recording of Nasca’s For You feed to Jennifer Harriger, a psychology professor at Pepperdine University in California. Harriger has spent the past five years studying the impact social media can have on adolescents, especially when it comes to body-image satisfaction. Her experiments with hundreds of college students have shown that exposure to idealized body types on social media can lead to less satisfaction with one’s own appearance. Most recently, she’s focused on TikTok’s algorithm, but she says her research has been limited by the company’s lack of transparency. “There is no effective way to study it, because we don’t know how it works,” she says.

After a few minutes of watching on her phone, Harriger pauses the recording. “This is an onslaught of sad, depressing and hopeless content,” she says. Even for her, “it was very emotionally triggering, and I’m able to more logically process what I saw. When a teen that has a vulnerable brain is viewing this content, they will have a stronger response. And that’s very scary.” She says Nasca’s feed “is certainly not appropriate for a teenager.”

In a 2022 research paper, The Dangers of the Rabbit Hole, Harriger and three colleagues wrote that it’s “ultimately the responsibility of the social media corporations that create and implement the algorithms to protect their users from harm.” Some American lawmakers are trying to send just that message. Bills have been proposed at the state and federal levels to force tech companies to put children’s safety ahead of profit-driven interests. The US Supreme Court is also expected to rule this term on a case challenging Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects social media companies from being sued for content posted on their sites.

More than 200 lawsuits have been filed against social media platforms since the start of 2022, many of them arguing that, even if the companies can’t be held liable for the content posted on their platforms, they should be accountable for harms built into their products. The suits include at least two dozen filed by school districts against some combination of Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube and their parent companies, alleging that they’re responsible for the country’s youth mental health crisis.

Many of the others have been filed by the Social Media Victims Law Center, the Seattle-based firm that’s representing the Nasca family. In more than 65 cases, the center alleges that social media products have caused sleep deprivation, eating disorders, drug addiction, depression and suicide. Laura Marquez-Garrett, one of the center’s attorneys, says the lawsuits against TikTok argue that its algorithm is designed to target vulnerabilities. “There’s a really dark side of TikTok that most adults don’t see,” she says. “You could have a child and a parent in the same room, together watching TikTok on their phones, and they’d be seeing an entirely different product.”

Among the center’s cases are ones filed on behalf of two teenage girls recovering from eating disorders: Nuala Mullen, who’s 18 and from New York state, and Katie, who’s 14 and from Virginia and who asked that her last name not be used so her anorexia issues don’t follow her for life. Both say they liked to watch silly dance videos and funny clips on TikTok, but in 2021 they noticed their For You feeds started featuring unsolicited videos about how to get skinnier legs and consume fewer calories in a day. “I do not remember searching any of that stuff at all, and then it was there,” Katie says.

They say they became obsessed with the app and, over time, grew isolated from their friends and family. “It felt super lonely, and TikTok was kinda just there,” says Katie. In January 2022, the day after her 13th birthday, she had to be hospitalized, her resting heart rate so low that her life was in danger. Mullen was hospitalized the same month, with the same symptoms. “That algorithm is designed to get kids to harm themselves in ways they don’t even know how,” says Mullen, whose suit also names Meta and Facebook. Both cases are ongoing.

“Our children are dying,” Marquez-Garrett says. “They are developing harmful dependencies on these products, and they are experiencing unprecedented rates of depression, anxiety and suicide. How many 16-year-olds killing themselves does it take for people to realize this is not OK?”

(From left) Michelle viewing Chase’s iPad; photos of Chase in the Nasca home.

Photographer: Kylie Corwin for Bloomberg Businessweek

“My life is f---ing miserable!” a man in a TikTok video yells. “I hate my f---ing life, I hate it,” he screams.

Michelle Nasca is sitting at the kitchen table of her family’s blue-shingled house on Long Island in February, watching videos from Chase’s TikTok feed on an iPad. “This is what I get every time I open his account,” she says, her cheeks wet with tears. The man onscreen continues his tirade. Michelle’s hands begin to shake. Her husband, Dean, watches over her shoulder, grimacing. “It’s sick, that’s what it is,” he says. “Where are the happy videos? There’s nothing happy here.”

Before Chase’s death, the Nasca family had an ordinary suburban life. Michelle, a flight attendant, and Dean, an accountant, lived in their five-bedroom home with their three boys. The kids spent their summers biking around town or boating to Fire Island. Chase was an overachiever. At 4, he would fill in the answers to an older brother’s math homework. As a teenager, he was an honors student, competed on the high school swim team and played for an Olympic development soccer team. “He never showed any signs of being depressed,” says his soccer coach, Kurt Kelley. “He was a good teammate, a good captain, a good friend.”

Nasca’s soccer jerseys outside the house.

Photographer: Kylie Corwin for Bloomberg Businessweek

He liked Harry Potter, steakhouses and social media. He would sit in the car on his way to soccer practice, headphones in, glued to the screen. His parents didn’t think much of it or ask to inspect his phone. He was keeping on top of his grades and training schedule, and they didn’t want to interfere with the little freedom he had.

They did use the phone to track his location, though. That was how his mother knew something was wrong that evening in February 2022. Just before 7 p.m., she checked Chase’s location to see when he’d be home. The small blue dot showed he’d left the gym, but it wasn’t moving. She refreshed the screen, zoomed in and saw he was at the railroad crossing. She called his phone, and it went straight to voicemail.

Michelle got in her car and drove toward the tracks. As she neared them, she saw a stationary train, its lights flashing. The conductor was outside and told her to stay back. She started running up and down the tracks, peering under the wheels, screaming Chase’s name.

A memorial to Nasca.

Photographer: Kylie Corwin for Bloomberg Businessweek

The first days after his death were a whirlwind of disbelief, grief and insomnia. When police returned his bike and his iPhone, Michelle switched the phone on and found that it still worked even though its screen was smashed from the train’s impact. But she didn’t have Chase’s six-digit passcode, and there were a million potential combinations. She kept trying to unlock the phone anyway—it gave her purpose and served as a welcome distraction.

She took the device to an Apple store, but the manager said he couldn’t unlock it for privacy reasons. A local IT specialist couldn’t get in, either. The police wouldn’t help, since Chase had died by suicide, not homicide. Finally, Michelle realized she could reset Chase’s TikTok and Snapchat passwords by selecting “forgotten password” and getting a link sent to his backup email address, which was actually her own. She doesn’t really know what she was looking for. But when she opened the TikTok account, she says, she found it. The app was “glorifying and normalizing suicide,” she says.

The Nasca family decided to sue TikTok after talking to the Social Media Victims Law Center. “People need to know about the dangers of social media,” Dean says. “Chase wasn’t bullied. He had a great group of friends, and he was excelling academically and athletically. He wasn’t doing drugs, he wasn’t drinking, so what was the variable that was introduced that put him over the edge? I can only conclude it’s this constant barrage of TikTok videos.”

Whatever role Nasca’s For You feed may have played in his death, excerpts from an exchange he had with someone on TikTok offer some insight into his frame of mind the day he died.

At 9:09 a.m., while in class, Nasca sent a private message to a user he followed who posted a lot of depression-related content. He’d never met the user and didn’t know his real name. Yet that day he sought solace from this stranger. Their conversation (excerpted here) lasted throughout the school day.

“Might not make it past today, I’m tired of thuggin’ it out,” Nasca wrote at one point.

“I know how you’re feeling 100%,” the other user replied. “I really hope you stay alive. It’s not worth leaving.”

“I’ve been telling myself that for so long. I no longer find enjoyment in anything. Any soccer practice I go to I’m anxious I’ll f---up, even going to the gym or playing video games is boring now.”

“It’s def hard to find joy and happiness in life and personally, I’m still searching. I get being at your limit, but not giving up is what makes you strong. Nobody has to know the shit you go through.”

“I’m ok with no one knowing. I think I like it better that way. When I think about my future, I just can’t envision myself being happy, I can’t envision myself having a gf/wife/family. I’ve just lost passion because of being depressed all the time.”

The conversation wrapped up as the school day finished. Then, at 6:29 p.m., about 10 minutes before his death, Nasca sent one final message.

“Hey bro, if I’m not here tomorrow, I ask that you remember me and forgive me.”

If you or someone you know needs help with thoughts of suicide or self-harm, a global list of help lines is available here.

- alf9872000

-

1

1

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.