Stafford and his Apollo 10 shipmates still hold the speed record on a crew spacecraft.

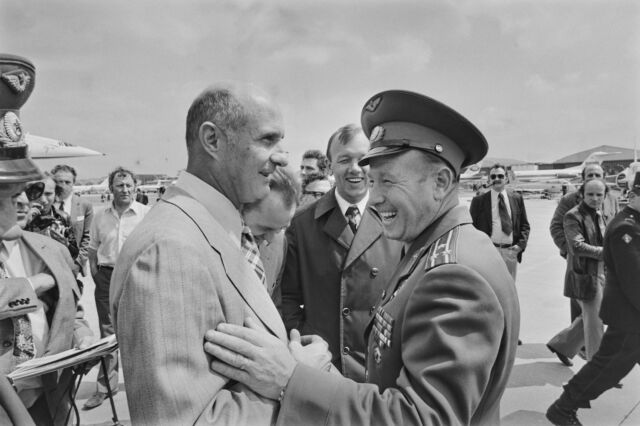

Apollo commander Tom Stafford (left) with Soyuz commander Alexei Leonov during the Apollo-Soyuz mission

in July 1975.

NASA

Former NASA astronaut Thomas Stafford, a three-star Air Force general known for a historic handshake in space with a Soviet cosmonaut nearly 50 years ago, died Monday in Florida. He was 93.

Stafford was perhaps the most accomplished astronaut of his era who never walked on the Moon. He flew in space four times, helping pilot the first rendezvous with another crewed spacecraft in orbit in 1966 and taking NASA's Apollo lunar landing craft on a final test run before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon in 1969.

By his own account, one of the greatest moments in Stafford's career came in 1975, when he commanded the final Apollo mission—not to the Moon but to low-Earth orbit—and linked up with a Russian Soyuz spacecraft carrying two Soviet cosmonauts. The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) planted the seeds for a decades-long partnership in space between the United States and Russia, culminating in the International Space Station, where US and Russian crews still work together despite a collapse in relations back on Earth.

"Today, General Tom Stafford went to the eternal heavens, which he so courageously explored as a Gemini and Apollo astronaut as well as a peacemaker in the Apollo-Soyuz mission," said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. "Those of us privileged to know him are very sad but grateful we knew a giant."

According to a report in The New York Times, Stafford's wife, Linda, said he had recently been diagnosed with liver cancer.

No false moves

Stafford was born in Weatherford, Oklahoma, on September 17, 1930. He was a child of the Dust Bowl and dreamed of becoming a pilot from the time he was in grade school. After graduating with honors from the US Naval Academy, Stafford switched services and joined the Air Force, where he trained as a fighter pilot.

He attended the Air Force's Experimental Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California, then became a test pilot and instructor. He authored textbooks and flight manuals used by later classes of test pilots, some of whom also went on to become astronauts.

In 1962, NASA selected Stafford as one of nine test pilots for the agency's second class of astronauts. Within two years, NASA assigned Stafford to fly on the first flight of the Gemini spacecraft, the two-man capsule designed to demonstrate spacewalk techniques, rendezvous, and docking, key capabilities to future Apollo flights to the Moon.

But Stafford's commander on Gemini 3, Alan Shepard, was grounded for health reasons. NASA opted to swap them for the mission's backup crew, and Stafford had to wait to fly on Gemini 6 a few months later.

That mission, which was supposed to attempt the first docking between two spacecraft in orbit, didn't get off to an auspicious start. Commander Walter "Wally" Shirra and Stafford were supposed to guide their Gemini spacecraft to a linkup with an unpiloted target vehicle called an Agena, which would launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida, about 90 minutes before Gemini 6, which sat on a different launch pad a couple of miles away.

"We could hear it roar off the pad, and 90 minutes later, when it came across the Cape, we were going to go," Stafford recalled in a 2015 oral history interview with NASA. The launch failed, and the Agena target vehicle did not make it into orbit, so Gemini 6 was grounded.

Within a few weeks, NASA officials devised a new flight plan for Gemini 6. This new mission, called Gemini 6A, would rendezvous with the Gemini 7 spacecraft in December 1965, less than two months after their launch was scuttled due to the Agena failure. This wouldn't achieve the goal of physically docking two spacecraft in orbit, but it would get close, allowing NASA and its crewmen to demonstrate two capsules could fly in formation while orbiting the Earth.

This was an essential capability NASA had to prove in order to meet President John F. Kennedy's goal of landing astronauts on the Moon by the end of the 1960s.

"You got to remember, the whole thing, we’re building this big building at the Cape, with the giant Saturn V (rocket), the lunar module, command module, all based on doing a rendezvous around the Moon," Stafford said. "Nobody had ever done one. That was critical. Everything was based on rendezvous."

Astronaut Tom Stafford in low-Earth orbit on NASA's Gemini 9A mission.

NASA

With Gemini 7 already in space, Stafford and Schirra strapped into their seats again to launch on the renamed Gemini 6A mission. As the countdown reached zero, they felt the engine on their Titan II rocket rumble to life more than 100 feet below. But the rocket didn't go anywhere, and the engines shut off moments later.

It was a hair-raising moment. Schirra had his hand on a D-ring between his legs, ready to eject himself and Stafford out of the capsule for what would surely be a violent ride. If Schirra pulled the handle, the mission would be ruined, the spacecraft destroyed, and the astronauts would risk injury or worse. The Gemini spacecraft was pressurized with pure oxygen prior to launch. Lighting off the rockets of the astronauts' ejection seats in that environment could be disastrous.

"We didn’t do a thing," Stafford said. "We had lots of simulations of hold kills, but none exactly like that. But we knew in the seat of our pants that we hadn’t lifted off. We also didn’t know about (how it would react in) 100 percent oxygen ... We had been soaking like that for two hours. Shoot, if we’d fired that, bang, pyrotechnics, open the hatches and snub them, fire the rockets, boy, you’d see two Roman candles going up."

Technicians discovered an umbilical plug prematurely fell from the bottom of the rocket, causing the engine shutdown. But that wasn't the only problem. One of the rocket's two engine chambers was already losing thrust before the countdown cut off, and inspections revealed someone left a dust cover in the engine during manufacturing.

In three days, those problems were resolved, and Gemini 6A lifted off on December 15, 1965.

Schirra and Stafford flew their spacecraft within about a foot (30 centimeters) of Gemini 7, which carried astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Lovell on a two-week flight in orbit, the longest human spaceflight mission to date. Gemini 6A returned to a splashdown after about one day in orbit.

The Gemini 6 spacecraft, carrying astronauts Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford, is

seen from the window of the Gemini 7 spacecraft on Dec. 4, 1965.

NASA

Stafford's second mission, Gemini 9A, came less than six months later. He took command of Gemini 9A after the prime crew, Elliot See and Charles Bassett, died in an airplane crash in February 1966. Eugene Cernan was Stafford's crewmate on Gemini 9A.

The flight plan for Gemini 9A was supposed to be similar to the original profile for Gemini 6, with the objective of docking with an Agena target vehicle in low-Earth orbit. Gemini 8, commanded by Neil Armstrong, achieved the first docking with an Agena on the preceding Gemini mission.

But once again, the Agena didn't make it into orbit due to a rocket failure. NASA launched a backup target a couple of weeks later, but the aerodynamic shroud protecting it during launch failed to properly jettison. Gemini 9A launched anyway, and Stafford and Cernan approached the target vehicle several times before NASA officials abandoned the docking demonstration.

Cernan went ahead with a planned spacewalk on Gemini 9A, but the excursion was mired by trouble. Cernan's spacesuit became rigid as it pressurized, and he had difficulty maneuvering outside the spacecraft. His spacesuit visor started fogging up, and Cernan barely made it back inside the spacecraft. The astronauts safely returned to Earth after nearly four days in space.

Boulders down below

Stafford's next mission, Apollo 10, was the dress rehearsal for Armstrong and Aldrin's Apollo 11 landing. He paired up with Cernan again to test the Apollo lunar module on the Moon, taking the spidery-looking spacecraft within 47,000 feet of the lunar surface on May 22, 1969. Astronaut John Young flew with them to the Moon but stayed behind in lunar orbit to take care of the Apollo 10 command module.

The Apollo astronauts named their spaceships after characters in the Peanuts comic strip. The command module was christened Charlie Brown, while the lunar module got the name Snoopy.

Flying slightly higher than an airliner at cruising altitude, Stafford and Cernan marveled at the Moon's appearance. Large boulders—perhaps as big as Houston's Astrodome, Stafford later recalled—filled their narrow field of view as they peered out of Snoopy's windows

"There's enough boulders around here to fill up Galveston Bay," Stafford said. "It looks like we're getting so close, all we have to do is put the tail hook down and we're there."

Even if Stafford wanted to, and he wished he could have, the Snoopy was too heavy and didn't have enough fuel to make it down to the Moon's surface and then back into orbit. "My lunar module was too heavy to land. I would have been out of fuel," he later said. "Neil had the first lightweight lunar module, and he landed with 17 seconds of fuel. So I wish could have, but no dice."

Apollo 10 commander Tom Stafford reaches out to touch a Snoopy plush figure, as he walks

toward an elevator inside crew quarters at NASA's Kennedy Space Center.

NASA

Stafford and Cernan had a close call as they prepared to jettison Snoopy's descent section and fire the spacecraft's ascent engine to rocket them back toward Young and the Apollo 10 command module, Charlie Brown.

"The whole damned spacecraft started to tumble and tried to rotate," Stafford recalled in 1997. "I just reached over and blew off the descent stage, because all the thrusters were on the ascent stage, (to) get better torque-to-inertia ratio."

Stafford's intervention worked, and Snoopy reunited with Charlie Brown in lunar orbit. The Apollo 10 astronauts came back to Earth on May 26, 1969, hitting the top of the atmosphere at a top speed of 24,791 mph (39,897 kilometers per hour), still the fastest velocity achieved by any vehicle carrying humans.

Handshake in orbit

Following Apollo 10, Stafford served as chief of NASA's astronaut corps for nearly two years and then took a job as deputy director of flight crew operations. In 1971, he traveled to Moscow to represent the United States at the funeral of three Soviet cosmonauts who died in space on Soyuz 11, which depressurized just before reentry.

Around the same time, officials in the US and Soviet governments were discussing plans for a joint space mission, called Apollo-Soyuz or Soyuz-Apollo, depending on which side of the Iron Curtain you resided on. President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin signed an agreement in 1972 approving the project. NASA named Stafford commander of the Apollo portion of the mission the following year.

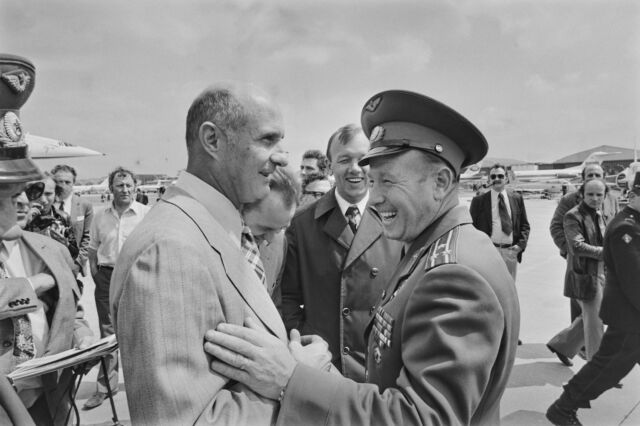

NASA astronaut Tom Stafford (left) greets Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov at the Paris Air Show

in 1973, two years before the Apollo-Soyuz mission.

Reg Lancaster/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

NASA astronauts Vance Brand and Donald "Deke" Slayton rounded out the Apollo crew. Alexei Leonov, the first person to perform a spacewalk, commanded the Soyuz spacecraft. He was joined by cosmonaut Valery Kubasov.

Apollo-Soyuz was emblematic of a détente in the Cold War. This provided an opening for the joint space mission, which President Kennedy first proposed in the early 1960s.

Speaking in 2015, Stafford said he and his Apollo-Soyuz crewmates preferred to focus on the mission's technical challenges rather than its geopolitical implications. "We kept politics completely out of it," he said. "We never discussed politics. It was just the mission and we were going to make it a success."

For one thing, engineers needed to devise a way for Apollo and Soyuz to dock with one another. This required the design of a new docking mechanism, with an airlock in between the ships, which operated with entirely different atmospheres. Apollo's crew cabin was pure oxygen and low pressure, while Soyuz was kept at sea-level conditions, with the same mix of nitrogen and oxygen as Earth's atmosphere.

Stafford was a one-star Air Force general when he flew on Apollo-Soyuz in July 1975. Before becoming an astronaut, Stafford viewed himself as a "cold warrior" eager to fight communist forces in Korea or elsewhere. But he became fond of Russia's space program, particularly Leonov, whom he considered "like a brother."

"We had a very, very good team," Leonov said in 2005. "We understood each other. It was a necessary condition of our cooperation."

The handshake in orbit between Stafford and Leonov is an enduring image. Stafford, speaking Russian with a thick Oklahoma drawl, said, "May our joint work in space serve for the benefit of all countries and peoples on the Earth."

Apollo-Soyuz was a one-off mission, but it paved the way for deeper cooperation in space between the United States and Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union. Russian cosmonauts flew on the space shuttle, and nine space shuttle missions docked with Russia's Mir space station in the 1990s, rotating US astronauts in and out on long-duration stays.

Now, the United States and Russia are again geopolitical adversaries, and nearly all semblance of cooperation between the two nations on Earth has withered. Still, though, both nations rely on one another to maintain and operate the International Space Station, which has now been in orbit for more than a quarter-century.

Stafford retired from the Air Force in 1979 and continued traveling to Russia for the rest of his life. He adopted two Russian children and attended the funeral of Leonov, the legendary cosmonaut, in 2019.

Never fully embracing retirement, Stafford remained an active participant in NASA's human spaceflight programs and chaired a study in 1991 advising the White House on how NASA should set off to, once again, explore the Moon and eventually send people to Mars. Stafford was "instrumental" in involving the Russians on the ISS program, according to an obituary posted on the website of the Stafford Air & Space Museum in his Oklahoma hometown.

After the death of seven astronauts aboard the space shuttle Columbia in 2003, Stafford co-chaired an oversight committee charged with assessing NASA's compliance with the recommendations of the independent investigation into the accident. Stafford served as chairman of NASA's ISS Advisory Committee until his death.

Speaking to public audiences in the last few years, Stafford still displayed an encyclopedic knowledge of his space missions, reciting numbers and statistics as if he was reading a checklist. Perhaps, then, it's no surprise that in his autobiography Carrying the Fire, the late astronaut Michael Collins wrote that Stafford had a "fantastic memory and eye for technical facts and figures."

Stafford, Collins wrote, was the "world's greatest human computer."

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.