“Tumplines allow one to carry heavier weights over larger distances without getting fatigued."

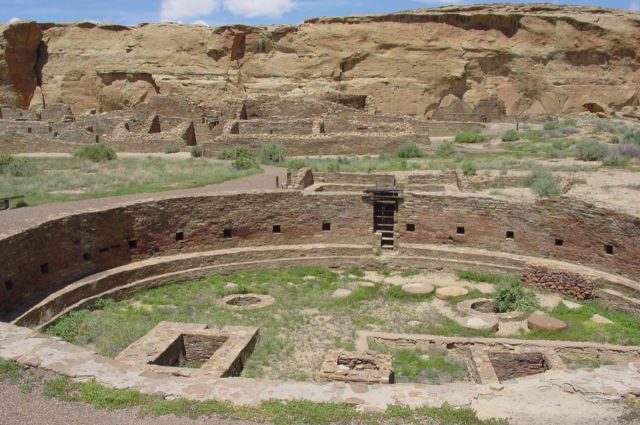

The so-called "great houses" of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico may have taken decades or longer to construct. Most large complexes had four or five stories and averaged over 200 rooms, with the largest boasting as many as 700 rooms. The complexes also featured large circular ceremonial areas called kivas. To construct these great houses, archaeologists have estimated that the Chacoans would have needed wood from some 200,000 trees, and those 16-foot-long wooden beams must have been transported from mountain ranges as far as 70 miles (110 km) away.

Many scientists have hypothesized about how the Chacoans might have accomplished this feat. The latest theory is that the Chacoans may have used simple devices called tumplines, still favored by sherpas in Nepal, according to a new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. To test that hypothesis, co-authors Rodger Kram and James Wilson spent the summer of 2020 training until they could haul a heavy log some 15 miles using tumplines. "Some people baked sourdough bread during COVID," said Kram, an emeritus professor of integrative physiology at the University of Colorado at Boulder. "Instead, we carried sand and heavy logs around using our heads."

There are no preserved timber scrape marks near the site, and the people of Chaco Canyon didn't have draft animals or even wheels, according to Kram and his co-authors. So the logs must have been carried by people, most likely along the wide roadways that linked this world. A 1925 publication featured a photograph depicting eight young men from Zuni Pueblo carrying a log: four on each side holding thin cross-poles at hip height, with the log laid on top. That photograph influenced many of the proposed mechanisms for transporting the logs. However, Kram et al. pointed out that there's no clear evidence that the residents of Zuni Pueblo share cultural connections with the people who once inhabited Chaco Canyon. "We feel that it is dubious to infer Chaco era timber transportation methods from a staged 20th century image," they wrote.

Others have suggested that the timbers were rolled rather than carried to construction sites, perhaps bundled within smaller wood pieces for protection or carried on the shoulders. And the published oral traditions and ethnography of the Pueblo and Dineo peoples descended from the Chachoans don't shed much light on the issue, either. There is one account of the timbers for Pueblo Bonita being hauled on little wagons made of a small tree, with a cross-section at either end serving as a rudimentary wheel. But that account is inconsistent with the known sourcing of the timbers—the Chuska, Zuni, San Mateo, La Plata, ad Sa Juan Mountains—and there is also no archaeological evidence for the existence of such carts, according to the authors.

Enlarge / The ruins of Chetro Ketl in Chaco Canyon, featuring the complex's great kiva.

Pubic domain

Kram developed his own theory about how the Chacoans managed the feat, starting with his realization a few years ago that the assumptions since 1980 about the mass of a typical roof beam (viga) used in one of the great houses was likely too high: 275 kilograms, a bit more than 600 pounds. “I cut a 1-foot-long section of pine and weighed it on my bathroom scale,” said Kram. “I multiplied by 16 feet and realized, ‘That can’t add up to 275 kilograms.’”

He and Wilson, who was then an undergraduate in biochemistry at the University of Colorado, Boulder, read up on the properties of dried wood and published their conclusions last year. They estimated that a 16-foot-long pine log weighed closer to 85 kilograms, or just over 185 pounds. That changed the calculation significantly when determining how many people would have been needed to carry the timbers 60-70 miles. And they decided to test whether the journey was possible themselves.

The first method they tried was carrying a log on their shoulders. “It was just debilitating,” Kram said. “It’s just a dumb way to carry a heavy object.” There are depictions of tumplines on ceramic effigies excavated from areas near Chaco Canyon, and archaeologists have found preserved tumplines made of yucca fiber at the site, so it seemed like a strong candidate for a method of efficient log transport. A tumpline is basically a strap attached to both ends of a load, worn over the top of the head just back from the hairline. By leaning forward, the carrier's back can then help support the load. “Tumplines allow one to carry heavier weights over larger distances without getting fatigued,” said Wilson.

Rodger Kram and James Wilson used devices called tumplines to carry a log weighing more than 130 pounds for 15 miles.

Kram and Wilson recruited co-author Joseph Carzoli, a strength and conditioning coach, to help them train for the physical test of their tumpline hypothesis. They wanted to determine whether multiple carriers, each using a tumpline, could transport timbers over a distance of 25 kilometers per day and also to determine how much the loads would slow down the steady, preferred walking speed. They built their tumplines from nylon webbing with plastic buckles and a bit of foam padding for extra comfort. They used plastic pipe to make artificial training logs with removable rubber end caps so they could be loaded with sand or lead shot to get different desired weights.

The men trained six to seven days a week, for 10 to 60 minutes per day, gradually increasing the log load to reach the desired mass of 30 kg each. They first alternated between short-duration sessions with heavier loads and long-duration training sessions with lighter loads. By the 45th day, they could keep the loads at the target mass while gradually increasing the duration of their sessions. By the end of the training, both Kram and Wilson could carry 30 kg logs for 60 minutes on their own with no pain other than some slight discomfort from the strap rubbing into their heads.

Every week during the training period, Kram and Wilson would also practice carrying a long, actual log using tumplines along a fire road in rural Boulder County, gradually increasing the size and weight of the log. When they were ready for the final test, they cut an air-dried piece of ponderosa pine timber to the desired size (2.53 meters long, 24 cm diameter) and weight (60 kg).

Enlarge / Wilson and Kram rest their log on supports called "tokmas."

Patrick Campbell/CU Boulder

For the logistical run-through, they successfully walked 8 kilometers (about 5 miles) carrying the load between them with tumplines. They used sticks called tokmas to support the timbers whenever they took breaks. The following week, they managed 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) in a single day. It took nine hours and 44 minutes, counting breaks. Actual walking time was five hours and 34 minutes, amounting to an average walking speed of 4.5 km/hour (about 2.8 mph). That was only 10.5 percent slower than their preferred walking speed without carrying the log.

They concluded that the tumpline method would have been entirely feasible for transporting logs to Chaco Canyon, estimating that it would take a team of three porters to move a typical 85 kg timber over a distance of 100 km. Verbal communication was critical to correctly time the lifting and positioning of the log, and Kram and Wilson quickly learned to synchronize their steps during transport so that the timber load swayed less, giving them more control. And they greatly appreciated the use of tokmas during rest breaks, which allowed them to rehydrate and reposition the load if necessary without having to fully unload and reload the log.

"To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical evidence relating to the method of timber transportation to Chaco Canyon," the authors concluded. "Tumplines were clearly used to transport many goods across Chaco World and our study has demonstrated the feasibility of using tumplines to transport timbers.... We believe that our experiment provides a parsimonious and unified explanation for how the people of Chaco accomplished the monumental feat of hauling 200,000+ trees across the San Juan Basin."

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.