This week's unanimous vote on phenylephrine's ineffectiveness was decades in the making.

After spending decades on pharmacy shelves, the leading nasal decongestant in over-the-counter cold and allergy medicines has met its downfall.

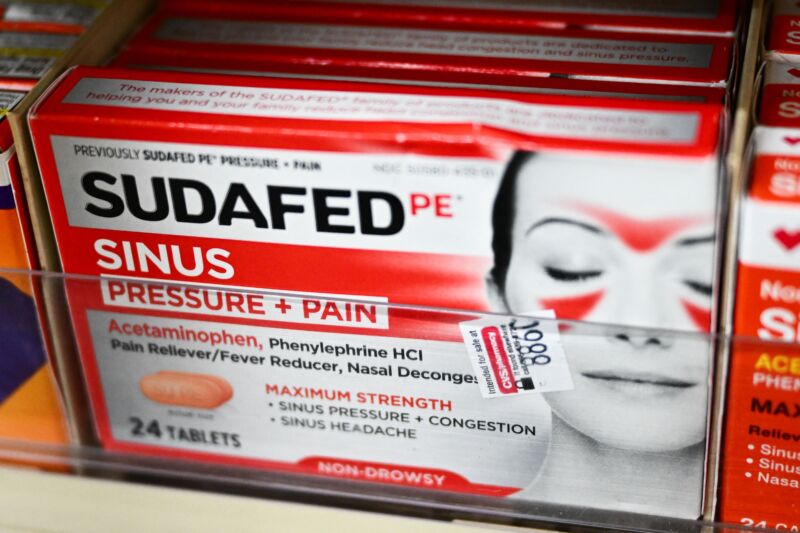

Advisers for the Food and Drug Administration this week voted unanimously, 16 to 0, that oral doses of phenylephrine—found in brand-name products like Sudafed PE, Benadryl Allergy Plus Congestion, Mucinex Sinus-Max, and Nyquil Severe Cold & Flu—are not effective at treating a stuffy nose.

The vote was years in the making. In 2007, amid doubts, FDA advisers called for more studies. With the data that has trickled in since then, the agency's own scientists conducted a careful review and came to the firm conclusion that oral phenylephrine "is not effective as a nasal decongestant."

Looking back, the FDA noted that key data supporting its original acceptance of phenylephrine in 1976 was likely "too good to be real." And looking forward, the agency saw a bleak future for the drug. While this week's vote concluding ineffectiveness applies only to the oral dosages currently approved for use, the FDA found that higher, potentially more effective doses of the drug could significantly increase blood pressure, posing a safety risk. "[T]here may be no path to evaluating higher doses," the agency concluded.

To be clear, the advisers did not discuss phenylephrine-containing nasal sprays, which do appear to have some efficacy. And, most importantly, the safety of phenylephrine-containing products is not in question; the FDA and its advisers did not raise any safety concerns. It's safe, just useless.

Rise and fall

It's still unclear how the FDA will proceed following the advisory panel's vote, which it is not obligated to heed but usually does. But it's certainly possible that widely used phenylephrine-containing medicines could eventually disappear from drug store aisles.

In a clarifying statement Thursday, the FDA noted there will not be a swift blowout of the popular decongestant. If the agency acts on the advisers' votes and decides to wipe it off its list of effective over-the-counter drugs (the "OTC monograph"), the agency would first have to propose the removal from the monograph, then provide a public comment period, issue a final ruling, and work with manufacturers to reformulate products.

Still, however slow the process, if the FDA strips phenylephrine from the monograph, it will undoubtedly upend the over-the-counter cold and allergy medicine market. Popularity of phenylephrine skyrocketed after 2006, when its leading competition moved behind the pharmacy counter.

The "Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005" went into effect that year, restricting sales of the more effective drug pseudoephedrine, which could be diverted to making methamphetamine. As pseudoephedrine use dropped, phenylephrine's rose. By 2022, the FDA estimates that Americans bought 242 million phenylephrine-containing products, taking the lion's share of the decongestant market and generating nearly $1.8 billion in sales.

Given phenylephrine's overwhelming market success and complete clinical failure, it's worth revisiting how we got here—and the FDA provides a deep dive on just that. The agency notes that the original 1976 acceptance of phenylephrine was based on just 14 studies—only 12 of which included efficacy data, and of those, only seven reported some level of positive efficacy data (though most were weakly positive). Eleven of the 14 studies were sponsored by a drug maker. Last, all of the studies used a dubious measure of nasal airway resistance to assess effects on congestion. This is a highly variable, unvalidated method that is no longer accepted by the FDA in clinical trials.

Original regulatory review

Overall, the FDA determined that the original 14 studies were all small and had numerous statistical and methodological problems, with mixed results. While the FDA considered these problems to be "valid and overwhelming" across all the studies, the agency homed in on two specific studies for extra scrutiny. The two studies were done at one study center, Elizabeth Biochemical labs, which conducted a total of five of the 14 studies on phenylephrine. While some of the Elizabeth studies reported relatively weak positive results, two were strongly positive. They were so positive, in fact, that they tipped the scales for the initial determination of efficacy.

But, on closer inspection, the FDA found that they "were not only the most positive studies, but they also produced near textbook perfect results that could not be duplicated in other similarly designed studies that used the same methodology but were conducted at two other centers by the same sponsor," the FDA wrote. The agency noted that even at the time, scientists from other study sites were puzzled as to how the Elizabeth site had gotten such strong, clear results. Some of them even visited the Elizabeth site to observe testing there in an effort to determine what the difference was, but ended up walking away "without a satisfactory answer."

The FDA was so skeptical of these Elizabeth studies the agency strongly suggested there were "data integrity issues" at the site, and that the results "reflect data that are simply too good to be real." As such, the agency conducted a forensic analysis on the data, including looking for digit preference in the last significant digit of reported data. While one of the studies passed this test, the other failed, revealing that it had "a disproportionately high occurrence of the digit '5'," which provided "sufficient statistical evidence to cast doubt upon the results."

Damning data

Phenylephrine is a specific alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist in blood vessels—that is, the drug binds to a specific cellular receptor in blood vessels, which causes them to constrict. Narrowing blood vessels in the nose is how phenylephrine supposedly works to reduce congestion. The common cold and allergies cause blood vessels in the nose to become wider, which is followed by increased mucus production and narrowing of nasal passages. Constricting the blood vessels helps prevent that downstream stuffiness. Pseudoephedrine works in a similar but less specific (more effective) way.

While constricting blood vessels in your nose can help relieve stuffiness, constricting blood vessels all over the body can increase blood pressure, as well as heart rate and jitteriness. This is why people with high blood pressure are cautioned about using cold medicines with decongestants. But for phenylephrine, FDA clinical pharmacologists found that clinically relevant blood pressure changes weren't seen until the maximum oral dosage approved is at least doubled. Early on, the lack of big increases in blood pressure and heart rate were positive safety data, but in retrospect, it was also a clue that the oral doses were ineffective.

In the past reviews, outdated methods suggested that oral doses of phenylephrine resulted in 38 percent bioavailability of the active version of the drug after ingestion. But modern studies have suggested that phenylephrine is highly metabolized in the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in less than 1 percent bioavailability of the active drug.

Since the 2007 FDA meeting, there have been three clinical trials on phenylephrine—two by Merck for treatment of seasonal allergies and one by Johnson and Johnson on treatment of the common cold. All used clinically acceptable designs and nasal congestion symptom scores as a way to measure decongestant efficacy. "These three trials represent by far the largest and most carefully constructed trials that have ever been performed to evaluate the decongestant effect of oral [phenylephrine]," the FDA wrote. And all three found no significant difference between phenylephrine and placebo.

“A done deal”

After reviewing all of the data and the FDA's analysis, the agency's advisory committee agreed unanimously that phenylephrine is not effective.

"This is a done deal as far as I'm concerned," Paul Pisarik, a voting committee member and an expert in family medicine and epidemiology at Archwell Health in Oklahoma, said after the vote. "It doesn't work."

Pisarik, like many of his fellow committee members, said they did not support doing future studies on efficacy of phenylephrine because the current body of data is already conclusive. "We're kind of beating a dead horse," Pisarik said. Other members noted that while phenylephrine is not in itself unsafe, its use could be unsafe in that it could delay effective treatments.

Jennifer Schwartzott, the patient representative on the panel, emphasized that consumers deserve to treat their symptoms safely and effectively. "I feel that this drug in this oral dose should have been removed from the market a long time ago."

After the vote, the industry group Consumer Healthcare Products Association (CHPA), which represents makers of phenylephrine-containing products and also gave a presentation at the FDA meeting defending effectiveness, released a statement by CHPA President and CEO Scott Melville. "We are disappointed by the outcome of today’s FDA Advisory Committee meeting because its non-binding recommendation is at odds with the numerous clinical trials and previous regulatory determinations affirming oral [phenylephrine] as a safe and effective decongestant at its labeled dose," Melville said.

While phenylephrine remains on the market—for now at least—it's likely many consumers will want to avoid buying products containing it moving forward. In its statement Thursday, FDA noted that some products contain only phenylephrine, while others are combination therapies that have multiple active ingredients to treat multiple symptoms.

"[T]he presence of phenylephrine in these products does not affect how other active ingredients work to treat those symptoms," the FDA wrote.

"Because a variety of different drug products may be sold under the same brand name, consumers should always read the drug facts label to determine which ingredients are in a medication, as well as important warnings and directions for use."

- BobikH, Adenman and Karlston

-

3

3

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.