Tête de Moine is often served by scraping the top of a cheese wheel in a circular motion with a special tool.

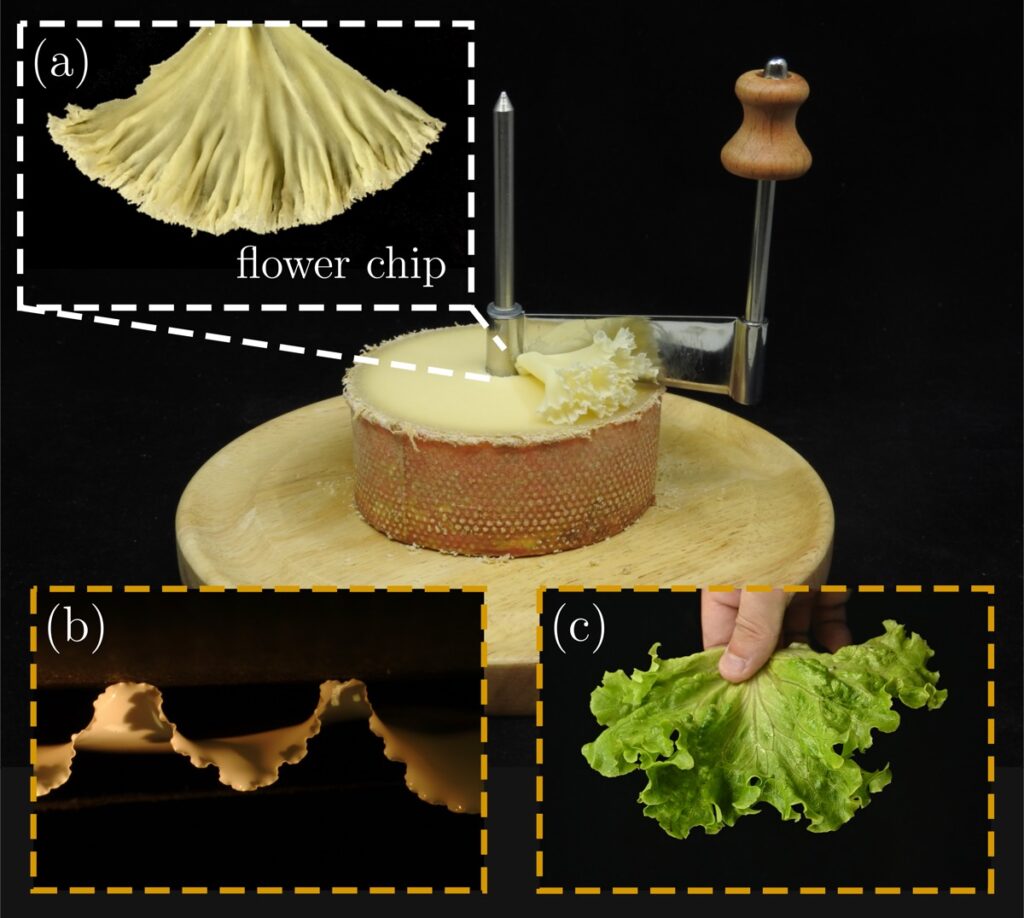

Cheese connoisseurs are no doubt familiar with a particular kind of semi-hard Swiss cheese called "Tête de Moine." Rather than spreading or slicing the cheese, Tête de Moine is usually served by scraping the top of the cheese wheel in a circular motion using a specialized tool called a Girolle. This produces elegant thin shavings known as rosettes, since they resemble a frilly flower.

The method is both aesthetically pleasing and serves to enhance the aromas and mouth feel of the cheese, according to the authors of a new paper published in the journal Physical Review Letters (PRL). This group of physicists based in Paris noted a marked similarity between the frilly edges of those cheese flowers and certain leaves, fungi, corals, and even torn plastic sheets—all formed by different mechanisms. So naturally the physicists decided to conduct their own research to determine the underlying mechanism(s) for the delicate frills of Tête de Moine shavings.

Tête de Moine translates as "monk's head," and the name dates back to the 1790s, although the actual cheese originates back to a 12th-century Bellelay monastery in Switzerland. It's made from raw unpasteurized cow's milk and is matured for a minimum of 75 days on spruce boards and boasts a firm reddish-brown crust. The Girolle (named after the French word for chanterelles, which have a similar rosette shape) is a more recent innovation, invented in 1982 specifically for Tête de Moine by a man named Nicolas Crevoisier. It's just a round wooden plate with a pin stuck vertically in the middle—the better to skewer one's cheese wheel—and a crank handle to control the slicing blade.

a) Layer of the cheese Tête de Moine with wrinkly edge, after being scraped using the cheese slicer “la Girolle.”

(b) Edge wrinkling of a torn plastic sheet. (c) Wavy edge of a BlueStar Fern leaf.

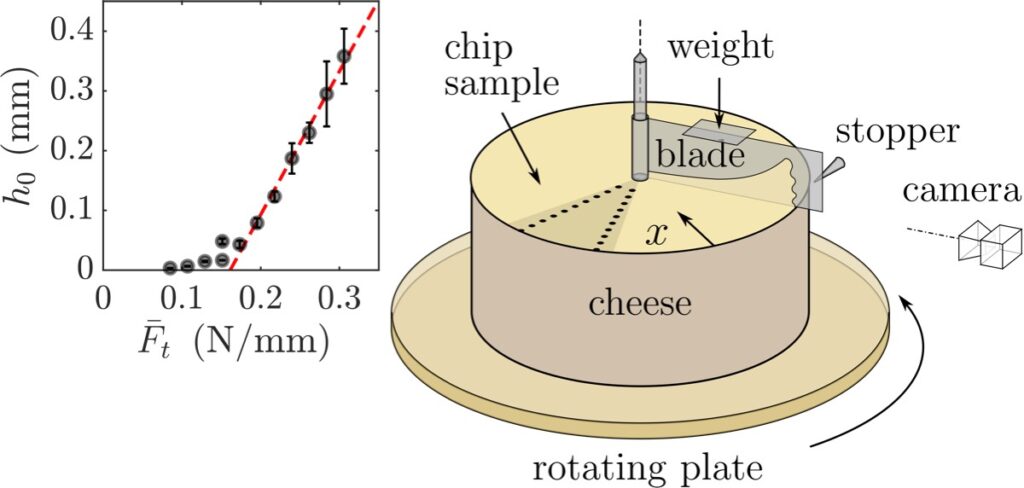

For their experiments, the authors of the PRL paper selected samples of Monk's head cheese wheels from the Fromagerie de Bellelay brand that had been aged between three and six months. They cut each cheese wheel in half and mounted each half on a Girolle, motorizing the base to ensure a constant speed of rotation and making sure the blade was in a fixed position. Their measurements of how the cheese deformed during scraping enabled them to build a model based on metal dynamics on a two-dimensional surface that had "cheese-like properties."

The results showed that there was a variable friction between the core and the edge of the cheese wheel, because the core stayed fresher during the ripening process. Because the harder outer edge had lower friction with the blade, the edges of the cheese shavings were uneven in thickness—hence the resemblance to frilly rosettes.

This essentially amounts to a new shaping mechanism with the possibility of being able to one day program complex shaping from "a simple scraping process," per the authors. "Our analysis provides the tools for a better control of flower chip morphogenesis through plasticity in the shaping of other delicacies, but also in metal cutting," they concluded. Granted, "flower-shaped chips have never been reported in metal cutting. But even in such uniform materials, the fact that friction properties control the metric change is particularly interesting for material shaping."

Physical Review Letters, 2025. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.208201 (About DOIs).

Hope you enjoyed this news post.

Thank you for appreciating my time and effort posting news every day for many years.

News posts... 2023: 5,800+ | 2024: 5,700+ | 2025 (till end of April): 1,811

RIP Matrix | Farewell my friend ![]()

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.