The placement of the more than 2,400-year-old gear suggests its owner was on a final ride

A woman buried more than 2,400 years ago in what’s now northwestern China has galloped into a scientific afterlife atop the earliest directly dated horseback riding saddle.

Researchers have radiocarbon dated the well-preserved, soft saddle to 727 B.C. to 396 B.C. Excavated at what’s known as the Yanghai cemetery, this expertly crafted piece of riding equipment is about as old as, or possibly older than, the previous record holders, archaeologist Patrick Wertmann of the University of Zurich and colleagues report in the September Archaeological Research in Asia.

Soft saddles found in tombs of mobile herders and warriors from the Scythian Pazyryk culture of northern Asia date to 430 B.C. to 420 B.C. Those dates are inferred from analyses of tree rings in wood that was used to construct those chambers.

Despite its simple design, “the Yanghai saddle was manufactured by a specialist familiar not only with needle- and leatherwork but with horse riding and the anatomy of horse and rider,” Wertmann says. The finished product, which showed signs of extensive use, had been placed with the deceased woman’s body in a position for her to take another ride.

It shares basic features with present-day soft saddles, including two wing-shaped hides sewn together to form a seat, divided by a long, narrow strip of hide that was placed over a horse’s spine. Rounded pieces of hide attached to the front and back of the wing-shaped pieces would have helped riders to maintain an upright position and raise themselves up, say when shooting an arrow.

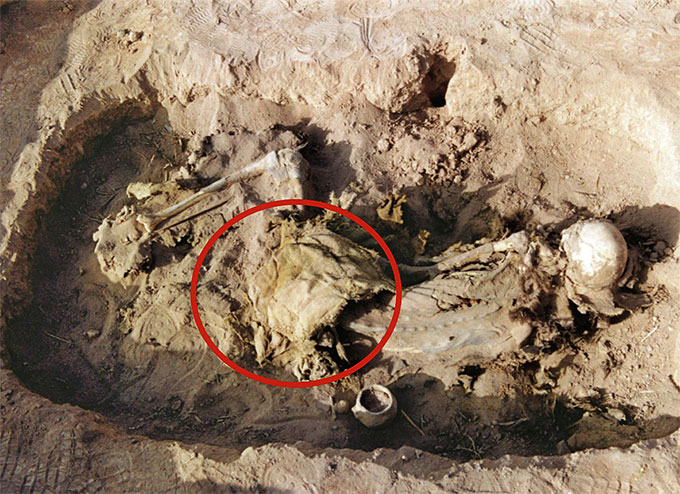

A more than 2,400-year-old saddle found in western China showed signs of extensive use and had been placed with a deceased woman’s body in a way that suggests she might be riding still (marked by the red circle).

P. WERTMANN ET AL/ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN ASIA, 2023

Different stitching techniques using either sinew or leather thread hold the Yanghai saddle together. Saddle stitching, a method still practiced today that creates two rows of interlocking threads using a single row of holes, connected front and back supports to the saddle seat. Simpler stitching methods were used to repair tears in the saddle and to close incisions in each main hide that could be opened to stuff animal hair and straw into the saddle seat for cushioning.

When and where people began to ride horses and use saddles remains uncertain. Yamnaya herders living in the area of modern Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary may have ridden horseback as early as around 5,000 years ago, based on an analysis of the herders’ skeletal features (SN: 3/3/23). Ancient artwork from around 4,800 years ago in Mesopotamia shows horses being ridden without saddles, Wertmann says.

But only saddles provide clear evidence of horseback riding, says anthropological archaeologist Alicia Ventresca-Miller of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Subtle construction differences between the Yanghai saddle and others found at several regional sites, presumed to be of around the same age as the Yanghai find, “suggest that knowledge of saddle-making was being transferred between [communities] that then made variable types of saddles,” says Ventresca-Miller, who did not participate in the new study.

At Yanghai, where 531 tombs have been excavated, researchers have recovered whips, bridles and other items associated with horseback riding that date to as early as around 3,300 years ago. Only one other grave aside from the woman’s tomb, thought to be of about the same age, has yielded a saddle. But that find is fragmentary and has not been radiocarbon dated.

Yanghai excavations have also produced the oldest known pair of pants, worn by a horseback rider around 3,000 years ago (SN: 2/18/22).

Saddle-making emerged later, as riders became concerned with their own comfort and safety and the health of their horses, Wertmann suspects. Comfortable saddles would have enabled everyone in a community to ride horses and spurred increases in long-distance horseback trips, Ventresca-Miller says.

Wertmann’s team cannot say whether Yanghai people, who lived in year-round settlements, or a mounted herding community from elsewhere in Central and East Asia made the ancient woman’s saddle. She may have migrated to Yanghai from a herding group and brought the saddle along. Or Yanghai people may have acquired the saddle through trade. Or local experts in leather and needlework may have crafted the saddle.

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.