We picked 20 time-travel movies and rated them by scientific logic and entertainment value.

Since antiquity, humans have envisioned various means of time travel into the future or the past. The concept has since become a staple of modern science fiction. In particular, the number of films that make use of time travel has increased significantly over the decades, while the real-world science has evolved right alongside them, moving from simple Newtonian mechanics and general relativity to quantum mechanics and the notion of a multiverse or more exotic alternatives like string theory.

But not all time-travel movies are created equal. Some make for fantastic entertainment but the time travel makes no scientific or logical sense, while others might err in the opposite direction, sacrificing good storytelling in the interests of technical accuracy. What we really need is a handy guide to help us navigate this increasingly crowded field to ensure we get the best of both worlds, so to speak. The Ars Guide to Time Travel in the Movies is here to help us all make better, more informed decisions when it comes to choosing our time travel movie fare.

This is not meant to be an exhaustive list; rather, we selected films that represented many diverse approaches to time travel across multiple subgenres and decades. We then evaluated each one—grading on a curve—with regard to its overall entertainment value and scientific logic, with the final combined score determining a film's spot on the overall ranking. For the “science” part of our scoring system, we specifically took three factors into account. First and foremost, does the time travel make logical sense? Second, is the physical mechanism of time travel somewhat realistic? And third, does the film use time travel in narratively interesting ways? So a movie like Looper, which makes absolutely no sense if you think about it too hard, gets points for weaving time paradoxes thoroughly into the fabric of the story.

(Many spoilers below in the interest of meaningful analysis.)

Eric Bangeman

What modern science has to say about time travel can be summed up thusly: You can travel to the future, but you probably can’t travel to the past, although to be honest, we’re not really sure. Einstein’s theory of general relativity—which says that space and time are unified into “spacetime” and the curvature of spacetime gives rise to gravity—at least lets us contemplate the possibility of time travel in a scientifically plausible context. A “closed timelike curve” is a path through spacetime on which someone can move forward in time as far as their local perspective is concerned and nevertheless end up visiting their own past. Such a context, however, would involve astrophysically massive gravitational fields, possibly wormholes, and negative energies or something equally exotic. Essentially none of the films we will discuss even attempt to portray physically realistic time travel (with one exception, Interstellar, which is only a partial exception).

Even without scientific accuracy, we can still ask for logical consistency. Alas, that is also pretty thin on the ground, although in this case, there are true exceptions. The most straightforward way for travel to the past to make sense is if you can visit but you can’t actually change anything—“Whatever happened happened,” in the memorable formulation of fictional physicist Daniel Faraday in the TV show Lost. Physicists have dubbed this the “Novikov self-consistency principle,” but it can really just be summed up as “making sense." Somewhat more ambitiously, we can imagine one or more alternative parallel timelines that are created by a sojourn into history. For the most part, however, our cinematic heroes make a cheerful hash of logic and narrative sense as they traipse through their pasts.

Here are our 20 representative picks, discussed in chronological order of their release to highlight how the understanding and treatment of time travel in Hollywood has evolved over the decades. There are some truly delightful entries here (plus a few stinkers for balance), but our deep dive into the topic has convinced us that the perfect time travel movie has yet to be made. That's a worthy goal for future filmmakers to strive for.

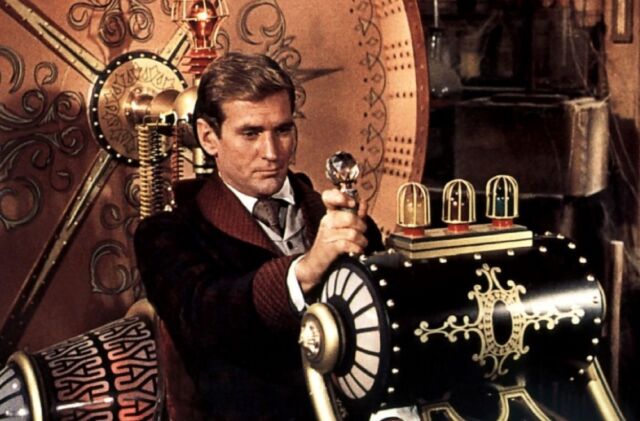

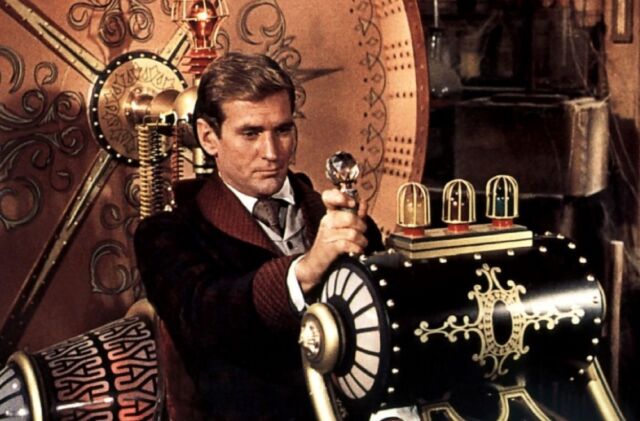

The Time Machine (1960)

Frankly, we'd prefer an enclosed time machine to an open sled.

MGM

Director George Pal's The Time Machine was the first feature film adapted from H.G. Wells' 1895 novella. The plot hews pretty closely to the novella, replacing the nameless Time Traveler with a fictional version of H.G. Wells himself (Rod Taylor), an inventor in Victorian London. Wells travels to 1917 and World War I; 1940 and the London Blitz; 1966 (where he narrowly escapes the detonation of an "atomic satellite"); and finally to the very distant future of 802,701, where he meets the Eloi and the Morlocks, before returning to 1900. Reviews were mixed and the film hasn't aged well, but it did win an Oscar for best special effects. The actual time machine is an iconic prop in film history—it's a sled-like design with a large clock-like rotating disk and a brass plate on the instrument panel identifying the inventor as "H. George Wells."

Wells’ original story was one of the first portrayals, in fiction or anywhere else, of the idea of other times as analogous to other locations in space—somewhere (or somewhen) you could visit and eventually return to your own time. Written two decades before Einstein proposed general relativity and curved spacetime and long before anyone thought to contemplate realistic time travel from a scientific perspective, Wells didn’t go into any detail about the mechanics. But the cinematic version nevertheless is relatively sensible.

The time machine may be an open sled (one might have asked for some enclosure before embarking on a journey through millennia), but at least it travels through time rather than magically teleporting through it. It’s unclear how it travels back to the past without running into itself, but that’s a quibble. As far as logic is concerned, there is surprisingly little to complain about. Our protagonist visits the future and eventually returns to his present before seemingly going back to the future again. Since he doesn’t visit the past, there really isn’t any opportunity to monkey with history as we know it.

Entertainment Score: 4

Science Score: 7

Superman (1978)

"You'll believe a man can fly": Christopher Reeve will always be our Superman.

Warner Bros.

No disrespect to other incarnations, but Christopher Reeve will always be our Superman, solely based on his performance in this 1978 film. Director Richard Donner gives us the canonical origin story: his infancy on the doomed planet Krypton and journey to Earth; his idyllic childhood in Smallville; and his extended education in the Fortress of Solitude at 18, emerging years later as a full-fledged superhero. He is Daily Planet reporter Clark Kent by day and a crime-fighting defender of truth, justice, and the American way on the side. So Superman inevitably comes into conflict with brainy arch-villain Lex Luthor (Gene Hackman, sporting a marvelous selection of outrageous wigs).

Its impeccable mix of action, humor, emotional resonance, and what were then groundbreaking special effects made Superman an instant classic. We're knocking off a point for the cheesy "Read My Mind" spoken song as Superman takes Lois Lane (Margot Kidder) on a romantic flight over Metropolis, which has aged poorly. But otherwise, Superman remains our favorite of the many adaptions and reboots centered on the character. (Skip the later "extended cut" with several deleted scenes added back in; Donner cut that footage for a reason, and the longer version is noticeably inferior to the theatrical release.)

Superman's inclusion on this list is due entirely to a key plot element in the final act: Superman fails to save Lois during a major earthquake in California, and the grief-stricken superhero defies his father's moratorium on interfering in human history by turning back time so he can remedy his mistake. Sorry, Supes fans, but the time travel here doesn’t make the tiniest iota of sense.

Our standards are admittedly lax when it comes to the physical mechanism by which cinematic heroes journey through time, but “flying really fast around the Earth so that it reverses the direction of its rotation and sends it back to a previous moment” is such thoroughgoing lunacy that one must almost pause in admiration. Then we return to our senses and ask, “Why does Superman’s flight have any effect on the rotation of the Earth? And what does that rotation have to do with the direction of time? Do I get younger if I start twirling counterclockwise?” No, dear reader, you do not. Indeed, by the rules handed down by Einstein, Superman’s near-speed-of-light journey would actually send him into the future, not into the past.

To its dubious credit, Superman pioneers two different flaws that will frequently recur in movies to come. First, time travel is portrayed as a miraculous cure-all, which is then never used again. Superman essentially goes back in time to save his girlfriend. This is admirable, but aren’t there other, more historically significant global disasters that could be averted by the same strategy? This is a narrative problem, not a scientific or logical one, but it rankles.

Then, of course, there is the flaw that almost always accompanies stories in which the past gets changed by time-travelers: Where did those time-travelers come from? We, the viewers, see a sequence of events that seems to make sense if we don’t think too hard. Lois Lane dies, Superman gets upset, he travels back in time, stops the events that led to Lois dying, and we live happily ever after. But at the end of this sequence, Superman still has the memory of Lois dying the first time around. Yet because he changed history, that event he remembers never happened. Lois certainly doesn’t remember it. How does he? One could try to finesse this question by introducing an alternative timeline, but the movie doesn’t do that (and first-timeline Lois would still be dead). This is the logical conundrum that plagues many time-travel stories to varying degrees of egregiousness.

Entertainment Score: 9

Science Score: 1

Time After Time (1979)

H.G. Wells (Malcolm McDowell) time travels to 1970s San Francisco in pursuit of Jack the Ripper.

Orion Pictures

Time After Time also features H.G. Wells himself (Malcolm McDowell), time-traveling to San Francisco in the late 1970s in pursuit of Jack the Ripper—aka, his former good friend Dr. John Leslie Stevenson (David Warner), who used the time machine to evade arrest after his most recent murder. Wells thought he was heading into a socialist utopia and is shocked to discover that the future is anything but. As Stevenson puts it when Wells tracks him down, in 1893's London Stevenson was considered a monster—"here, I'm an amateur." Wells must thwart the killer's plan to permanently steal the machine so he can continue butchering women throughout time.

Writer/director Nicholas Meyer based his screenplay on the premise of Karl Alexander's novel of the same name. McDowell originally planned to model his speech after Wells' actual voice but changed his mind after hearing a 78 rpm recording of the author, purportedly "absolutely horrified" at Wells' accent and high-pitched squeaky voice. McDowell opted for a more typical posh London accent for his performance. But other aspects of Wells' life and work remain intact; he even "arrives" in the middle of a San Francisco museum exhibit in his honor, conveniently replacing his glasses that broke en route through time with a fresh pair carefully preserved within his writing desk. Those little touches make Time After Time a genuinely charming and entertaining film.

If The Time Machine sticks safely with travel to the future while Superman monkeys shamelessly with the past, Time After Time is the first film on our list to intentionally use the possibility of altering the past to raise dramatic tension while ultimately explaining that everything is OK. It actually works pretty hard to make sense, even explaining how the time machine itself automatically returns to 1893 after Stevenson’s first trip, so it's there for Wells to use himself. It even explains why Wells climbs into the time machine in London and emerges in San Francisco: The physical machine itself continues to exist through time and had been moved in the meantime. (I guess Wells was time-traveling inside all along, somehow invisible to the moving company?)

But the real fun kicks in when Wells tries to convince his tentative love interest, Amy Robbins (Mary Steenburgen), of his story by traveling a few days into the future. There, they find a newspaper proclaiming that Robbins had just been the latest murder victim. That sets up a legitimate time-travel anomaly. But it's cleverly avoided when we learn that the true murder victim had been misidentified and wasn’t Robbins at all. To really wrap everything up, Robbins goes back with Wells to 1893, and they get married. History teaches us that H.G. Wells married his second wife, Amy Catherine Robbins, in 1895. This preserves a single sensible timeline—as long as there are no records of the historical Robbins existing before 1893.

Entertainment Score: 8.5

Science Score: 8

The Terminator (1984)

"I'll be back": This film established the basic rules of James Cameron's sci-fi universe.

Orion Pictures

This is the blockbuster science fiction action film that started it all, launching a hugely influential franchise and director James Cameron's highly impressive career. A cybernetic assassin, or Terminator (Arnold Schwarzenegger), travels back in time from 2029 to 1984 Los Angeles intent on killing a young woman named Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton). Unbeknownst to her, she will give birth to a son, John Connor, who will lead a future Resistance against a synthetic intelligence called Skynet, created by the US government as a military defense.

The Resistance sends its own champion back in time: a soldier named Kyle (Michael Biehn), who falls in love with Sarah and fathers John. The film's focused, relentless, horror-inspired plot delivered plenty of thrills, violence, and snippets of humor. The Terminator racked up an impressive $89 million worldwide against its $6.4 million budget. Terminator 2: Judgement Day will always be our franchise favorite by a long shot, but the original Terminator comes in at a solid second.

If Superman studiously ignores the potential inconsistencies in its treatment of time travel, The Terminator glories in them. They are the fulcrum around which the action pivots, although actual inconsistencies are largely avoided. The audience doesn’t raise too much fuss because the story is now told from the perspective of characters being visited from the future rather than going to the past themselves. They worry about their individual lives being in danger and the fate of the world. Philosophical coherence is low on their list of priorities.

The time-travel technology is once again basically magic, but in a particularly hilarious way: travel happens via “Time Displacement Equipment,” which can send things backward in time but not forward (the opposite of what physics would suggest) and only works on organic tissue. Physics has nothing to say about that last bit, other than to roll its eyes and shake its head in disbelief. It does let us check out Schwarzenegger’s unclothed body, which was a major selling point in 1980s action movies.

Skynet’s goal in sending the Terminator back in time is to prevent the birth of John Connor, who in 2029 is leading the Resistance. The problem is clear: the Skynet of 2029 might be upset that John Connor is winning, but it is well aware of the existence of John Connor. If its plan had worked, John wouldn’t have been born. So the Skynet that would have come into existence, if any, wouldn’t be the same as the Skynet that set the plan in motion. Either that version of reality would cease to exist (when?), or multiple realities would be created. Or the plan was always doomed to fail.

The movie goes with “doomed to fail,” leaving us with a single consistent timeline, although the threat of a different timeline has to be taken seriously if there is to be any dramatic tension. So, partial credit. Future installments in the franchise would decide that single timelines are boring and branch off too many universes to keep track of. This has served both to open up new dramatic possibilities and to give filmmakers the right to ignore anything portrayed in earlier movies that they didn’t approve of.

Entertainment Score: 9

Science Score: 3

Back to the Future (1985)

"You built a time machine... in a DeLorean?" That's the least of the time-travel issues.

Universal Pictures

No list like this would be complete without Back to the Future, arguably one of the most influential time-travel movies ever made, as well as an iconic comedy of the 1980s. Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) is accidentally transported back to 1955, thanks to his friend Doc Brown's (Christopher Lloyd) newly invented time machine—a plutonium-fueled DeLorean that goes into time-travel mode once it hits 88 mph. Marty inadvertently prevents his parents (Crispin Glover and Lea Thompson) from meeting and falling in love, placing his future in jeopardy. He must rectify that situation while a younger version of Doc helps him figure out how to generate the 1.21 gigawatts of energy needed to refuel the time machine to send Marty home.

Back to the Future is a terrific piece of entertainment, but scientifically, it has a lot to answer for. Director Robert Zemeckis co-wrote the script with Bob Gale, both of whom never liked the fact that most time-travel films followed the principle that the past was immutable. They specifically wanted to explore how the past being altered might affect the future, and the rest is film history.

In Avengers: Endgame (see below), there is a scene in which our heroes are discussing time travel, and Scott Lang (Ant-Man) looks around in dismay and says, “So Back to the Future’s a bunch of bullshit?”

[Full disclosure: this scene is Sean’s most notable contribution to popular culture. He was a science consultant on Endgame and expressed some version of this sentiment in a meeting with the writers and directors. Because, sadly, it’s true. It's a great movie, and the DeLorean makes for an undoubtedly stylish magic box; but as far as time travel goes, Back to the Future is a bunch of bullshit.]

Throwing caution to the wind, BttF makes it perfectly clear that Marty’s trip to the past wreaks all kinds of havoc on the present. You might expect some hints that there are multiple timelines going on, but there is only one timeline, and it is an unholy mess. If you handed Back to the Future a logic textbook, it would disdainfully throw it over its shoulder like Luke throwing away the lightsaber that Rey hands to him in The Last Jedi.

Let's focus on one infamous element. As Marty inadvertently interferes with events that led to his parents first getting together, we see Marty’s brother and sister fade out of a photograph that was taken in 1985. There is no plausible timeline in which the photo is there but the siblings aren’t in it. In the words of Bob Gale, “If you think about it too much, it really doesn’t make any sense. Who is going to take a photo of an empty wishing well?” But it’s worse than that. Why does the photograph fade then, i.e., in 1985? Marty’s shenanigans happened back in 1955. What kind of mystical cross-temporal connection must we imagine to make sense of such a delayed reaction?

Sean did once try to work this out. Is there any conceivable theory under which BttF-style time travel could possibly make sense? He came up with a candidate theory, explaining it in a podcast. Without going into too much detail, we need many timelines (one with the photograph, one without, etc.), and we also need a completely distinct “narrative time” representing the viewpoint of the audience watching the movie, stitching the one real timeline together from bits and pieces of all the alternative timelines.

Or we can just admit it’s a bunch of bullshit.

Entertainment Score: 10

Science Score: 1

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

The former crew of the USS Enterprise travels to Earth's past to save a pair of humpback whales.

Paramount Pictures

The Star Trek franchise has engaged in its share of time-travel shenanigans, and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home is a classic in that regard. This was the second film directed by Leonard Nimoy (who played the original Spock), a sequel to Nimoy's Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984) and completing a narrative arc that began with 1982's Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Nimoy wanted to do something lighter with no clearcut villain and an environmental message (the plight of humpback whales): "No dying, no fighting, no shooting, no photon torpedoes, no phaser blasts, no stereotypical bad guy." He brought on Nicholas Meyer (see Time After Time above) to co-write a new script, in which the (now former) crew of the USS Enterprise time travel to 1980s Earth to bring back a pair of humpback whales—the only species capable of responding to the signal from an alien space probe back in their future that now threatens the planet.

The result was a film that recaptured some of the charm of The Original Series, grossing $133 million worldwide against its $26 million budget and snagging four Oscar nominations for cinematography and sound. Meyer's script has a lot of fun with the time travel "fish out of water" elements, most notably Spock and Kirk encountering an annoying punk rocker on a public bus. (Spock performs his trademark Vulcan nerve pinch on the punk.) And who doesn't love McCoy griping in exasperation about primitive 20th-century medicine or Chekov earnestly asking random passersby about "nuclear wessels"?

According to special relativity, motion is relative. There is no absolute notion of how fast you are going, only a relative notion of your velocity with respect to something else. But there is an unbreakable speed limit, the speed of light, which looks the same to everyone. We can imagine hypothetical “tachyon” particles that can only go faster than light, but they don’t seem to exist in the real world, and ordinary particles can only move more slowly. If you could go faster than light, all hell would break loose—for example, it would be easy to travel backward in time.

The Star Trek universe very much relies on the idea that you can go faster than light; that’s what warp drive is all about. But there is an absolute notion of how fast you are going. So, Star Trek has to appeal to some laws of physics that are not compatible with Einstein’s theory. (This is fine, of course—it’s a movie.) If there is an absolute standard of rest, then going faster than light no longer immediately implies the ability to go back in time. Indeed, whenever Star Trek has used time travel, something over and above ordinary warp drive is needed; in The Voyage Home, they have to pass perilously close to the Sun. That doesn’t make actual sense, but it counts as a vague gesture toward general relativity, i.e., gravity is the curvature of spacetime. And the time travel is not the kind of magic-box-with-flashing-lights that we so often see in movies; it happens in a spaceship and involves astrophysically relevant masses and distances, which is all to the good.

Moreover, at least in this particular movie, the time travel is completely consistent. The crew worries about changing the past, but for the most part, they don’t actually do so. One possible exception is nicely finessed: Scotty offers a bit of 23rd-century technology (a formula for transparent aluminum) to a 20th-century engineer. Bones worries that this might change the course of history. Scotty replies: “How do we know he didn’t invent the thing?” This is clever but fraught. If the rules of time travel in this universe are “whatever happened happened,” then indeed Scotty’s offer is benign—necessary, in fact, if that’s what actually happened. But if those are not the rules, presumably a new timeline is born. Maybe one should be a bit more clear on what the rules are before messing around.

Let’s assume a single consistent timeline. One could reasonably ask who actually invented the formula for transparent aluminum. Textbooks in the 23rd century would have credited this 20th-century engineer, but we know that he got the idea from a 23rd-century visitor. The idea has no starting point; it travels in a closed loop. This is sometimes described as a “paradox,” but isn’t, really—it's not illogical; it's just weird from the perspective of our usual intuition.

One could question why Star Fleet doesn’t use time travel to solve its problems more often. In the larger Star Trek universe, time travel eventually becomes commonplace, leading to the “Temporal Wars,” after which the technology was banned. I’m sure that will completely prevent any future problems.

Entertainment Score: 6

Science Score: 8

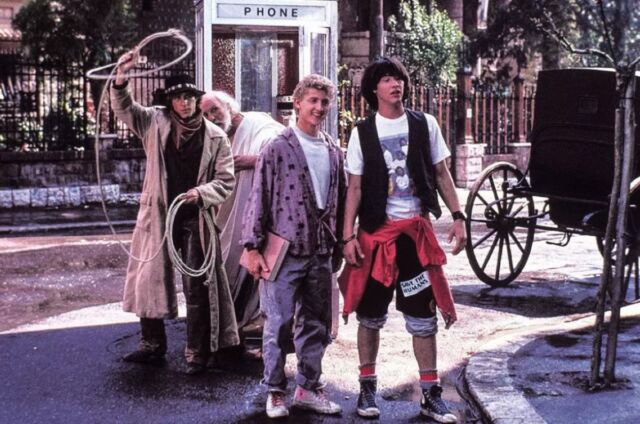

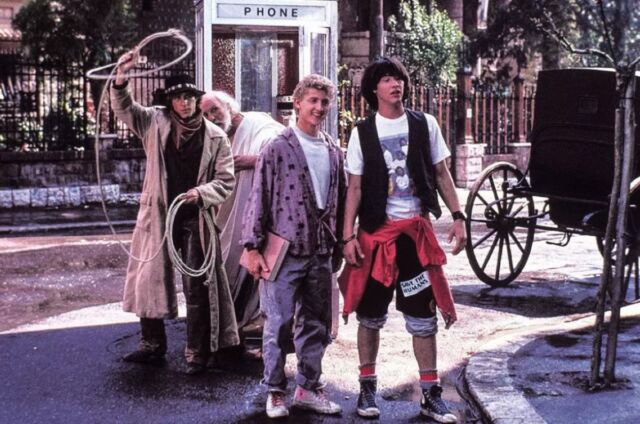

Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989)

Bill and Ted's Golden Rule: "Be excellent to each other."

Orion Pictures

Nobody expected this goofy, slapstick comedy to become a time-honored favorite that spawned two popular sequels (1991's Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey, and 2020's Bill and Ted Face the Music). But audiences couldn't resist the winsome charm of Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves), two scattered-brained high school students with big hearts and endless optimism who are in danger of flunking history. ("Dude. We are about to fail most egregiously.") If that happens, Ted's father will ship him off to a military academy, thus breaking up their band, Wyld Stallyns. But the band is destined to usher in a future utopia, which is now threatened.

With the help of a time machine in the form of a phone booth—provided by Rufus (George Carlin) from the year 2688—the pair travels through history, meeting Socrates, Billy the Kid, Sigmund Freud, Beethoven, Genghis Khan, Joan of Arc, and Abraham Lincoln, among others, bringing them back to 1989 for the history report to end all history reports. Napoleon naturally wanders off to the Waterloo local water park at one point, while the other historical figures wreak havoc at the mall. Watching Beethoven rock out on multiple electronic keyboards while Joan of Arc takes over an aerobics class is priceless. Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure wasn't exactly a box office smash, grossing a modest $40 million against its $10 million budget, but it's a film audiences have returned to again and again when they crave silly feel-good escapist fare.

If it’s been a while since you’ve seen Bill & Ted, you might remember the time travel as mostly harmless. It’s completely silly, of course. But historical figures are brought to the present and safely returned; maybe they just thought nobody would believe them if they told their stories. The bad news is that the plot never should have happened. Rufus comes to 1989 to help Bill and Ted pass their history exam. But they must have passed their exam, since Rufus exists and knows about their effect on the future. So what is he worried about?

The good news is that Bill & Ted contains the single most brilliant use of time-travel logic in cinematic history. The boys need their father’s keys, but don’t have time to fetch them. So in an intellectual leap that puts so many other time-travel protagonists to shame, they remember that they have a time machine. Bill: “After the report, we’ll time travel to two days ago, steal your dad’s keys, and leave ‘em here!” And indeed, they find the keys exactly where they did (will?) leave them, after their future selves pilfer them. Ted: “So, after the report, we can’t forget to do this, otherwise it won’t happen. But it did happen!”

All time travel stories should be like this.

Entertainment Score: 7

Science Score: 4

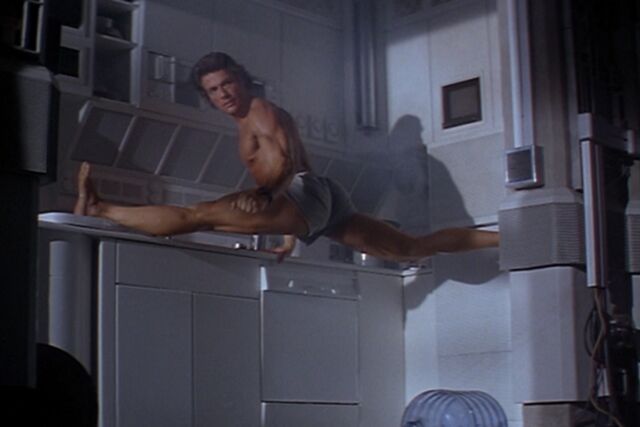

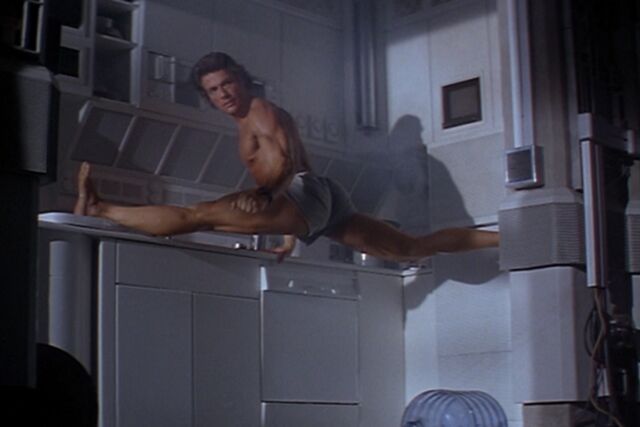

Timecop (1994)

We’re here for scantily clad van Damme gymnastics, not for narrative logic.

Universal Pictures

Directed by Mike Richardson, Timecop is based on a three-part Dark Horse Comics anthology story written by Mark Verheiden (who co-wrote the screenplay with Richardson). It's basically a cross between Lethal Weapon and The Terminator while never being as good as either of those two films. But it remains star Jean-Claude van Damme's most successful film—if only for the famous scene where van Damme jumps into the splits on a kitchen counter clad only in his underwear. Van Damme plays Max Walker, a DC Metro police officer who becomes an agent with the Time Enforcement Commission (TEC) in 1994 after the death of his wife Melissa (Mia Sara) in an attack by mysterious assailants. Ten years later, he must foil the plans of a corrupt senator (Ron Silver) who has been abusing the TEC's time-travel technology to raise funds for his presidential campaign, altering the future in the process.

Back to the Future gave license to time-travel stories to allow travel to the past to completely change the future, and filmmakers subsequently saw no reason to coax this particular genie back into its bottle. Timecop is constantly sending its characters into the past to address their present-time challenges, leaving them to return to a world that is changed in illogical but important ways. At least there are a couple of amusing wrinkles to contemplate. One is the statement that time travel allows you to visit the past and return to the present but not go to the future. That’s the opposite of the truth, as we currently understand it.

The other is just for the physicists, or perhaps for players of the video game Portal. Max Walker travels back to 1929 to apprehend a rogue time traveler planning to profit from the stock market crash. The suspect jumps out a window to his presumed doom until Walker follows suit and time-travels them both to safety. But why should a time jump change your momentum? It would be more realistic if both characters returned to the present and splatted into the floor with deadly force. At least the miscreant is sentenced to return to his original trajectory as a particularly fiendish version of the death penalty.

One last point: The movie begins with the death of the hero’s beloved wife, and you can probably guess that he will travel back in time to save her. So at the end of the movie, Walker returns to his now-living wife and their young son. But Walker doesn’t remember anything about his son’s life, which has been going on for several years now. Awkward. Also tragic, since presumably there was a version of Walker who has been raising this boy for several years now. What happened to him? For this reason, even though the time travel is, strictly speaking, no more illogical than Back to the Future, it gets an even worse science score. It’s one thing to be illogical. It’s quite another to leave us to contemplate the consequent existential horror of it all.

Entertainment Score: 3

Science Score: 0

12 Monkeys (1995)

Cinematic time travel came of age with Terry Gilliam's sci-fi masterpiece.

Universal Pictures

Director Terry Gilliam's 12 Monkeys is our top choice for a film that combines terrific storytelling and time-travel logic in a near-perfect union. It's inspired by a 1962 French short film called La Jetée. The film stars Bruce Willis as a convict from 2035 named James Cole, who is sent back in time to investigate the origin of a a deadly virus that appeared in 1996 and wiped out almost all of humanity, forcing any survivors to live underground.

A terrorist group called the Army of the 12 Monkeys is the prime suspect. The hope is that if the original virus can be found, it will help scientists in 2035 devise a cure. But Cole arrives in 1990 instead of 1996 and ends up in a mental institution, where he meets a fellow patient named Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt, in an Oscar-nominated performance). And he's haunted by a recurring dream involving a shooting at an airport. There are twists aplenty, but the viewer never loses the thread of the nonlinear plot, and the look and feel of the film harkens back to Gilliam's 1985 masterpiece Brazil.

Here is where cinematic time travel comes of age. Admittedly, no real effort is put into explaining how the time machine actually works, other than Gilliam’s signature steampunk wires and bellows. But the movie does a wonderful job of making you think that the future is being changed, before ultimately revealing that everything fits together in a beautifully interlocking whole. Willis stumbles around in the past, affecting many things without ever deviating from how things had always been.

Entertainment Score: 9.5

Science Score: 9

Donnie Darko (2001)

That mysterious fellow in a creepy rabbit costume will haunt your dreams.

Flower Films

This 2001 sci-fi psychological thriller was writer/director Richard Kelly's first feature film. Jake Gyllenhaal stars as Donnie, a psychologically troubled teenager who meets a mysterious figure in a creepy rabbit costume named Frank while sleepwalking one night. Frank tells him the world will end in 28 days, six hours, 42 minutes, and 12 seconds. When Donnie wakes up on a local golf course and goes home, he discovers a jet engine has mysteriously crashed into his bedroom, so his sleepwalking saved him from certain death. He keeps seeing Frank as events unfold, ultimately leading to tragedy and a strange vortex forming over Donnie's house that sends Donnie back in time to be crushed by the jet engine hitting his bedroom.

Donnie Darko had the misfortune to hit theaters six weeks after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks; audiences were just not in the mood for any film in which a crashing plane featured prominently. It has since attracted a significant cult following. Despite its flaws, there's something about this strange film that sticks with you, and it is certainly a unique, original vision.

Kelly released a director's cut in 2004 that expounded (poorly) on the philosophical and scientific underpinnings of his fictional world in greater detail, involving the spontaneous creation of an unstable Tangent Universe in which the film's events play out. Donnie's ultimate demise leads to the collapse of that Tangent Universe and restores the Primary Universe. Constructing a complete and internally coherent theory of the physical universe turns out to be hard, even when the universe is the real one and you can do experiments to check your math. A completely different kind of universe is even harder. So it’s maybe not surprising that the overexplained director’s cut of Donnie Darko wasn’t as satisfying as the more vague original. If we don’t know too much about what’s going on, it’s harder to complain about inconsistencies.

In the original movie, all we really know by the end is that a single jet engine falls off a plane on October 30, travels through some kind of wormhole, and lands on Donnie’s house on October 2. There are clearly two timelines: one where Donnie happens not to be home and is safe, and then an altered one where he is in bed and the engine kills him but, in the process, prevents the subsequent accident that kills his girlfriend Gretchen (Jena Malone). The upshot is pretty simple: Donnie has traveled back in time, changed the past, and that’s it. The “wormhole” is nothing like what physicists envision, although Kelly did take some inspiration from reading Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. There are also Donnie’s visions, which somehow come from the future, or at least rely on knowledge of future events. Physicists don’t really go there.

Entertainment Score: 5

Science Score: 4

Primer (2004)

Two engineers accidentally figure out how to time travel in this indie cult favorite.

IFC Films

This 2004 indie film about two engineers who accidentally figure out how to time travel has a strong cult following despite a confusing, unnecessarily complicated plot that makes Tenet (discussed below) seem simple and straightforward. Writer/director Shane Carruth (who also co-stars) has said he deliberately chose to make the plot incomprehensible to capture the inherent confusion of what he thought it would be like to experience the disorienting effects of time travel (namely, cumulative interference). Honestly, it might have worked, except he also deliberately chose to avoid any of the usual expository dialogue with regard to the scientific elements. This, too, can work in principle. Too often, exposition is a clumsy "as you know, Bob" affair. It's great that Carruth wanted authentic science-speak, but you've got to have a clear narrative as a trade-off.

Think of it as a good storytelling uncertainty principle: You can obfuscate the plot and not litter your dialogue with jargon, or you can keep the jargon and clarify the plot, even if it's just via a few well-placed signposts. Pick one. And while Carruth's overarching theme is the breakdown of Abe's (David Sullivan) and Aaron's (Carruth) friendship, neither character is sufficiently fleshed out to the extent that we care about their eventual estrangement. That said, Carruth did a great job making the most of his shoestring $7,000 budget; the stripped-down aesthetics of the production design work very well. But Primer is most certainly not the best time-travel movie yet made. It's more a cautionary tale of a filmmaker being a bit too clever for their own good.

As for the science, the basic idea is that Aaron and Abe are trying to build a device to counter the effects of gravity by creating a room-temperature superconductor (a hot topic in physics this year, albeit a controversial one) that exploits the Meissner effect to remove the magnetic field inside a plain gray box large enough to fit one person. (Carruth has said he was partly inspired by Feymann diagrams and the fact that elementary particle interactions are the same regardless of whether they happen "forward" and "backward" in time.)

We worry that Primer is so confusing that it bamboozled people into thinking that it would ultimately make sense if they could just put the pieces together. It doesn’t actually make sense. The time machine itself works pretty simply. You turn it on, wait a while, and then climb in and travel back in time to the moment you turned it on. The limitation that you can’t travel to times earlier than you turned the machine on is actually very realistic—closed timelike curves in relativity would have exactly that feature. But to travel around one, you would need a spaceship, not a standard magic box with some science buzzwords attached.

But the selling point of Primer isn’t the mechanics of time travel, it’s the consequences thereof. The characters are constantly interfering with past events, at one point even trying to prevent the time machine from being built in the first place. Multiple versions of history accumulate and overwrite each other. Is there any one sensible story to be told when the dust settles? We honestly don’t know. But the film has launched a thousand web pages and videos that gamely attempt to bring order to the chaos.

Entertainment Score: 2

Science Score: 3

Timecrimes (2007)

Who wouldn't be freaked out by the sight of a knife-wielding figure with bloody bandages on his face?

Karbo Vintas Entertainment

Written and directed by Nacho Vigalondo, this twisty, darkly humorous Spanish sci-fi thriller was partly inspired by a 1983 comic one-off called Chromocops by Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons. The film centers on a middle-aged man named Héctor (Karra Elejalde), who is renovating a house in the countryside with his wife Clara (Candela Fernández). One day, he finds a young woman naked and unconscious on the ground, and a mysterious man with bloodied bandages on his face stabs Héctor in the arm. A local scientist (Vigalondo) offers help by hiding Héctor in a strange mechanical device—but it's a time machine that sends Héctor back one hour in time, snaring him in a causal loop with multiple versions of himself. Wacky hijinks ensue.

If 12 Monkeys demonstrated that time travel can be dramatic and compelling even with just a single consistent timeline, Timecrimes boils that notion down to its essence, letting multiple time-shifted copies of the same character interact with each other in startling ways. Everything that happens makes perfect sense in retrospect, and you don’t need to watch more than once to follow the plot. Once it becomes clear that time travel is involved and there is a character whose face is hidden in bandages, it doesn’t take too much to guess that we’re seeing the main character come back from the future, but the way it works out is anything but obvious.

Entertainment Score: 6.5

Science Score: 9

Hot Tub Time Machine (2010)

The title of this gross-out screwball bro-comedy pretty much says it all.

MGM

The title pretty much says it all. There's a hot tub that turns out to be a time machine, transporting three middle-aged, depressed friends (and one teenaged nephew) back to their wild 1986 weekend at the Kodiak Valley Ski Resort. Directed by Steve Pink, Hot Tub Time Machine stars John Cusack, Rob Corddry, Craig Robinson, and Clark Duke, with a cameo by Chevy Chase as a hot tub repairman who might know more about what's happening than he's telling. Can the guys manage not to interfere with their past selves and irrevocably change the future while they figure out how to get back to their own time? It's a classic gross-out screwball bro-comedy (there are both R-rated and unrated versions) a la The Hangover, and the film is much better and funnier than the ludicrous title might suggest, thanks in large part to its hugely likable cast. Pink leans into the silly, and Josh Heald's script pokes playful fun at all the classic time-travel movie tropes.

You will not be surprised to learn that Hot Tub Time Machine doesn’t work too hard to maintain scientific plausibility in its portrayal of time travel. But there are nevertheless interesting and novel philosophical implications that the movie explores. This is the first movie on our list where it’s the character’s minds that travel backward in time, not their physical bodies; they end up inhabiting the bodies of their younger selves. (Peggy Sue Got Married did something analogous as early as 1986.) That’s not really a thing, scientifically speaking.

Is it really time travel at all? Sure—the characters’ actions in the past can, and do, change the future. And in a twist, those changes are largely for the better, at least from the characters’ perspectives. This is a departure from the standard time-travel nostrum that any change to the past runs the danger of making things immeasurably worse in the future.

Of course, it still makes no sense, bringing up the same kinds of issues we encountered with Timecop. Three of the characters leap back to their present, while one of them stays behind and lives through the intervening years once again. What were the other three doing for those years? Did their accumulated memories get coldly erased when the original characters returned from their temporal journey? Do we really care enough to ask?

Entertainment Score: 6.5

Science Score: 2

Looper (2012)

It's fresh and entertaining as storytelling but the time-travel science leaves much to be desired.

TriStar Pictures

Directed by Rian Johnson, Looper is a strikingly original dystopian time-travel tale. In 2044, a young man named Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) works as an assassin (or "looper") for a crime syndicate in Kansas City. The twist: The targets are sent back in time, hoods over their heads, from the year 2074, since it has become impossible to dispose of bodies undetected in the future. Loopers get paid in silver bars that are attached to the targets from the future. Should a looper live until 2074, he (or she) will be sent back in time to be killed by their younger selves, thereby "closing the loop" and terminating their contract. But what happens when a looper fails to kill their older self? That's Joe's dilemma when he encounters his older self (Bruce Willis) and the latter escapes.

As fresh and entertaining as Looper might be on the storytelling scale, its time-travel science leaves much to be desired. One of the most memorable scenes shows Joe's friend Seth (Paul Dano) in the present timeline being captured by the syndicate's "Gat Men" (basically enforcers), who are after his escaped older self. They carve an address into his arm, which instantly appears on the arm of Old Seth (Frank Brennan). Then the Gat Men begin methodically cutting off Seth's body parts as Old Seth desperately races to that address, losing fingers, a nose, and so forth before he is killed upon reaching his destination. It works incredibly well narratively, especially since we are never shown the graphic amputations on young Seth; just the aftermath on Old Seth. But as science? Not so much.

This movie embodies almost every way in which time travel might fail to make sense. The time-traveling victims materialize suddenly in the past, without any attempt at scientific justification. Joe’s actions dramatically change the future, so that he never would have come back to the present to set them in motion. Old Joe’s memories become sharp or fuzzy depending on whether time is about to be altered. (In the finished movie, Willis gruffly dismisses the idea that he should try to explain this, but there is a deleted scene in which he gives it a shot.)

And then, of course, there's that finger-cutting scene, a clear callback to the fading photograph from Back to the Future. Once more, it's hard to imagine how Seth’s fingers know when to disappear. When we think about it, it’s even worse than BttF, because Old Seth still has the memory of having had those fingers, even as he sees them disappearing before his eyes. So if we want to appeal to a theory where multiple timelines are knitted together in narrative time, we're forced to add one more zany feature: mind-body dualism, as in Hot Tub Time Machine. Seth’s final body has lived a different history than his final mind. Looper’s time-travel mechanics fail to make any normal kind of sense, but they do so in such an intentional way that it has to count for something.

Entertainment Score: 8.5

Science Score: 4

Safety Not Guaranteed (2012)

A moving exploration of why humans are so fascinated by the prospect of traveling back in time.

FimlDistrict

Director Colin Trevorrow shot this understated indie Sundance favorite on a shoestring budget with old Panavision lenses to capture the visual style and tone of 1970s auteur Hal Ashby (Harold and Maude, Shampoo, Being There). Screenwriter Derek Connolly was inspired by a 1997 joke ad in Backwoods Home by the magazine's editor, John Silveira, seeking "someone to go back in time with me" and including the line "safety not guaranteed." (Silveira was shocked to receive thousands of letters in response.) The film uses the ad's wording almost verbatim.

Aubrey Plaza stars as Darius, a disaffected recent college graduate interning at Seattle Magazine, who joins reporter Jeff (Jake Johnson) and fellow intern Arnau (Karan Soni) on a trip to Ocean Shores to track down the person who placed the ad: a paranoid grocery clerk named Kenneth (Mark Duplass). Darius goes undercover as a respondent to Kenneth's ad, and the two slowly bond over mutual loss in their pasts. Is Kenneth crazy, or is he really building a time machine? Much of the film hints at the former until the final shot. Safety Not Guaranteed is frankly rather light on the time-travel science. It excels in its moving exploration of why humans are so fascinated with the notion of being able to travel back in time—usually because so many of us long for the chance to right a wrong or correct a tragic mistake.

At this point in the maturation of time travel as a cinematic genre, most stories fall pretty cleanly into one of two distinct categories: “this is going to make sense, I promise” or “let’s just roll with it.” Safety Not Guaranteed is squarely in the latter. Kenneth wants to go to the past to save his former girlfriend Belinda, but it’s discovered that Belinda is still alive. She claims that Kenneth was never her boyfriend and gives a very different account of the accident that supposedly killed her.

When confronted with these inconvenient facts, Kenneth is able to explain them: He did (will?) actually travel back to the past and save Belinda, after all. This almost makes sense, even with just a single consistent timeline. But not really. The Kenneth we see in the movie has clearly lived through Belinda’s death and the aftermath, which shouldn’t be possible in a world where Belinda is currently alive and well—unless Kenneth is just lying about things, which seems completely plausible. That is ultimately the point, as the movie cares more about relationships and how we remember the past than the explicit mechanics of time travel.

Entertainment Score: 7.5

Science Score: 3

Predestination (2014)

This film is a loyal adaptation of Robert A. Heinlein's 1959 short story "—All You Zombies—."

Stage 6 Films

This 2014 sci-fi action thriller stars Ethan Hawke as Agent Doe with the Temporal Bureau, which is devoted to traveling back in time to prevent crimes from being committed. Doe is tasked with preventing the March 1975 bombing of a New York City public building but doesn't quite succeed, suffering severe burns as a result. An unseen person helps him grab his time-travel device to return to the Bureau in 1992, where he undergoes facial reconstruction surgery; his vocal cords have also been badly damaged, altering his voice. The Bureau wants him to retire but sends him back to 1970 for one final mission. Spanning events in 1945, 1963, and 1985, as well as the 1970s, Predestination is primarily concerned with whether or not it's possible to change the future, even with the advent of time travel. But the various parts don't add up to a compelling whole; the film flopped at the box office, grossing just $4.8 million against its $5 million budget.

Predestination is a loyal adaptation of Robert A. Heinlein's 1959 short story "—All You Zombies—," which has been held up as the last word in time-travel “paradoxes.” The main character is revealed to be their own mother as well as their own father. It’s the closed-loop problem we had with transparent aluminum in Star Trek: The Voyage Home, but now with an honest flesh-and-blood person rather than an abstract idea.

But of course, that’s not paradoxical at all, just not what we’re used to. A paradox is “X and also not-X,” not “I don’t know where X came from.” The film sticks closely to the major points of Heinlein’s puzzle-box plot, which ensures that everything makes sense at the end of the day. It’s an even more impressive act of following characters interacting with their past and future selves before tying things up in a tidy package than we found in 12 Monkeys or Timecrimes. So it's all the more regrettable that it’s just not that great a movie.

Entertainment Score: 3

Science Score: 9

Interstellar (2014)

The closest we’ve seen to a movie that tries to do time travel in perfect accordance with the laws of physics.

Paramount Pictures

In Interstellar, Earth in the distant future is beset by a devastating global famine that threatens to wipe out the entire human race. NASA scientists need to locate an exoplanet capable of supporting human life, and a former NASA pilot, Joseph Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), is tapped to lead a space expedition to three potential planets orbiting a supermassive black hole called Gargantua. The plot gets increasingly complicated from there, culminating with Cooper falling through a black hole and finding himself in a five-dimensional tesseract that enables him to communicate with the past—and ultimately save the day.

The premise of Interstellar came from Caltech physicist Kip Thorne and producer Lynda Obst, inspired by Thorne's research on black holes, wormholes, time warps, and other exotic concepts in theoretical physics. Initially, Steven Spielberg was meant to direct, but then Spielberg moved his production company to Walt Disney Studios, and Christopher Nolan took over directing duties. The CGI depiction of the film's rotating black hole, accretion disk, and gravitational lensing effect was based on advanced theoretical equations, and working on the project actually gave Thorne new scientific insights, resulting in three scientific papers—a prime example of science inspiring Hollywood and Hollywood inspiring science in turn.

Interstellar is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the closest we’ve seen to a movie that tries to do time travel in perfect accordance with the laws of physics. Or at least, with the laws of physics as they might plausibly turn out to be; physicists don’t know whether wormholes are actually allowed in the real world. But we're at least shown spaceships traveling through warped spacetime, which is how time travel should be. Yet while a wormhole features prominently in Interstellar, it’s not actually used for purposes of travel into the past, only as a cosmic shortcut through space. For most of the film, the only time travel we see is into the future, just as Einstein’s relativity would predict, via time dilation and hanging out in the gravitational field near a black hole.

It would be great to give it a 10 on the science scale. But the movie can’t quite be content with sticking close to known physics. Thus, we have Cooper visiting an inter-dimensional library and sending signals to his daughter in the past. This makes no sense (although, to be fair, it does preserve a single consistent timeline). It is vaguely inspired by some modern ideas of extra dimensions in string theory, but suffice it to say that those ideas would not allow you to poke books down from library shelves in the past.

Entertainment Score: 7

Science Score: 9

Arrival (2016)

Denis Villeneuve's first foray into sci-fi offers a fun twist on the ancient idea of prophesy or predestination.

Paramount Pictures

Arrival is based on a short story by Ted Chiang, who said he was partly inspired by the variational principle in physics. Director Denis Villeneuve's critically acclaimed fledgling foray into science fiction is a moody, leisurely paced, atmospheric film with big ideas and existential themes. Amy Adams turns in an amazing performance as linguist Louise Banks, who is called upon by the US government to make contact and communicate with aliens called "heptapods" (since they resemble cephalopods and have seven limbs).

Much of the film concerns Louise's attempts—working with physicist Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner)—to learn the aliens' palindromic language rendered in strange circular symbols. She gradually realizes that doing so alters her linear perception of time because the aliens experience events in time all at once rather than in succession. Louise begins experiencing "memories" of future events (i.e., premonitions) that include the future birth and eventual death of her daughter (with Donnelly) from an incurable disease. Louise nonetheless "chooses" to follow that same path, knowing it will end in tragedy, raising the age-old argument of whether free will is just an illusion. It's to Villeneuve's (and Adams') credit that the film works as well as it does.

Several of Kurt Vonnegut’s novels featured aliens from the planet Tralfamadore. They were not always portrayed consistently, but in Slaughterhouse-Five, they were said to exist at all times simultaneously, seeing the sweep of history as you or I would see pages in a book, all at once. The aliens in Arrival seem similarly equipped with the ability to perceive both the past and the future and to teach that ability to Louise.

This is a fun twist on the ancient idea of prophecy or predestination and, as such, makes for some compelling narrative uses—for a while, anyway. In the movie, Louise sees glimpses of what we initially assume to be the past but is eventually revealed to be the future. If she becomes good at this, she would become Laplace’s Demon, a hypothetical all-knowing intellect. The problem is that Laplace’s Demon lives an extremely boring life. There are no surprises, no anticipation, no tension, no risks.

Happily, none of us is Laplace’s Demon, nor will we ever be. There is no way to obtain all the necessary information about the current state of the physical universe, and if there were, there would be nowhere near enough calculational power to project it forward in time. Not to mention that the Demon was meant to illustrate a feature of classical Newtonian mechanics, and now we know that quantum theory injects a stochastic element that makes it impossible to predict the future well at all. Needless to say, Louise does use her precognitive powers to affect the present and thereby change history, but there seems to be only a single consistent timeline. Points awarded for exploring a novel twist on time travel, even if it likely wouldn’t stand up to close scrutiny.

Entertainment Score: 8

Science Score: 6

Avengers: Endgame (2019)

It's Captain America vs. Captain America thanks to time-travel shenanigans.

Marvel Studios

Directed by Anthony and Joe Russo, Avengers: Endgame is a direct sequel to 2018's blockbuster Avengers: Infinity War, bringing the narrative arc over 22 films full circle to an action-packed, emotionally powerful conclusion. After Thanos (Josh Brolin) erased half of all life in the universe with a snap of his fingers using the Infinity Glove, the remaining Avengers are despondent and directionless. Thanos destroyed the Infinity Stones after achieving his goal, dashing their hopes of reversing The Snappening. Then Scott Lang/Ant-Man (Paul Rudd) returns from the quantum realm, having only experienced five hours' time instead of five years. The team ends up traveling back in time via the quantum realm to retrieve the stones and bring the other half of the universe back. Endgame had one key element that Infinity War lacked: hope. Perhaps that's why it grossed a whopping $2.799 billion worldwide, compared to Infinity War's $2.052 billion.

As mentioned above, one of us (Sean) has a conflict of interest, having briefly served as a science consultant on this movie. In addition to sparking a couple of witty lines, that conversation did (one likes to think) help convince the directors that a single consistent timeline was ultimately the most satisfying way to go. Sean will also confess that he pitched an extremely elaborate and nuanced scenario by which multiple timelines could be magically sewn back together so that characters would subsequently have simultaneous memories of two very different histories. Marvel wisely didn’t take that suggestion. It’s always good to consult with physicists when you’re doing a wildly speculative science-fiction scenario, but you have to know when to ignore them.

Endgame ultimately stitches together a basically coherent timeline. There are bits like Ant-Man zipping into the quantum realm and coming back as a baby or an old man that make no sense, but they are largely played for laughs. The very invocation of the “quantum realm” isn’t grounded in any real science, but it does elevate the time-traveling slightly above the bare magic-box level. Invocations of the “Deutsch proposition” and the EPR paradox are nothing more than technobabble. And there are some stumbles of logic, as when Captain America (Chris Evans) fights himself. Wouldn’t the older Cap have remembered that event in younger Cap’s life?

However, the movie is a bit cagey about the nature of that timeline. The Ancient One (Tilda Swinton) explains that travel to the past has the capacity to lead to multiple branching timelines but also suggests that this would be bad. This would be developed in the TV series Loki into the concept of a “sacred timeline.” It's not a good concept. How do we know our intervention won’t make better timelines than the ones we know? It’s not exactly without its flaws.

Entertainment Score: 9

Science Score: 5

Tenet (2020)

The visual sequences of time running in reverse are a tour-de-force of filmmaking.

Warner Bros.

Christopher Nolan has the distinction of being the only director to appear twice on our list with Tenet, arguably his most ambitious and conceptually complex film to date. A character known only as the Protagonist (John David Washington) leads a covert CIA mission that goes awry. He ends up being recruited by a top-secret organization called "Tenet" that is trying to track mysterious artifacts with reversed entropy that move backward in time. Ultimately, the Protagonist and Tenet must foil a plot by future antagonists who are trying to reverse the flow of time to undo the devastating effects of climate change in that future.

It took Nolan five years to write the screenplay, and he was contemplating the central ideas for 10 years. But there's such a thing as overthinking things. Frankly, the plot is actually too complicated. Kudos to anyone who caught everything in a single viewing—especially the climactic "temporal pincer movement" and the multiple forms of palindromes embedded throughout—because we didn't. That makes it harder to connect emotionally with the characters, and the film is further marred by inexplicably poor sound mixing. But it's certainly an exciting film with fascinating ideas, and there's no denying that the visual sequences of time running in reverse are a tour de force of filmmaking. Small wonder that Tenet snagged an Oscar for Best Visual Effects; the honor was well-deserved.

Let us be perfectly clear: Physics doesn’t work this way. But the film uses physics concepts in an immensely clever way, breaking truly new ground in a genre where most terrain has been thoroughly explored. The “arrow of time” is a catch-all term for the various ways in which the past is different from the future. We have memories of the past but not the future; our actions today can affect the future but not the past. Modern science accounts for this via the notion of entropy, a measure of the disorderliness of a system. Our universe started (why, nobody knows) in a state of very low entropy, and it has been increasing ever since, a fact codified into the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Increasing entropy is responsible for why we remember the past and affect the future.

Tenet posits the ability to reverse the arrow of time for particular objects or people. You can enter a “turnstile” as a normal person and exit as a time-reversed person. So you should—and do —see yourself leaving one door at the same time as you are entering another. (Indeed, you are warned not to enter unless you see a time-reversed version of yourself leaving—something must have gone dramatically wrong.) This is cute and also not possible.

The reason that entropy increases for ordinary objects is not some inherent entropy-increasing tendency, which could somehow be reversed. Rather, it’s because of special conditions at very early times, near the Big Bang. You can absolutely imagine taking a system and delicately arranging the positions and velocities of all of its atoms so that its entropy goes down rather than up; it would look something like a trick shot in billiards that started with a scatter of balls and had them all converge into an orderly configuration as if they had just been racked. But if the billiard balls are disturbed along the way, the delicate arrangement would be ruined, and the trick would fail. Likewise, with Tenet’s backward-moving people and weapons, once they bumped into anything at all, they’d go back to evolving in the usual way.

Still, this is an example where, science-wise, we're inclined to cut some slack. Nolan is exploring something new and wild. Let him play around a little.

Entertainment Score: 8.5

Science Score: 7

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.