In 1866, a French engineer named Peccadeau de l'Isle was working on the construction of a railway line in southern France, digging for artifacts along the banks of the River Aveyron in his spare time. Some 23 feet (7 meters) down, he found a number of prehistoric flint tools and prehistoric art. They included the famed Swimming Reindeer sculpture and a carved spear thrower in the shape of a mammoth, as well as numerous engraved flat stones called plaquettes, all created by the Magdalenian people sometime between 16,000 and 13,500 years ago.

The finds caused a sensation at the time, mostly because they provided evidence of a colder climate during this period and that men had co-existed during the ice age with mammoths. A new analysis by English archaeologists of the limestone plaquettes excavated by de l'Isle concludes that the stones may have been placed around fire hearths. The team's digital reconstructions showed that the engraved images would appear to move and flicker in the firelight, amounting to a kind of animated "fireside art." The details appear in a new paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.

“This must have been quite a powerful visual effect,” co-author Andrew Needham of the University of York told New Scientist—particularly in the context of a campfire. “This was likely an important social space. It might have been a place to share stories or chat and bond with each other after long days spent out in the landscape hunting and gathering. The art is not just the engraved lines on the rock, but those engraved lines experienced under the correct conditions of darkness and roving light. It changes our appreciation of what art was and how it was used by Magdalenian people.”

Earlier cave-art lighting discoveries

In fact, the lighting conditions would have been very similar to those for prehistoric cave paintings, which also may have played with light and shadow to create "protomovies." That's a concept that surfaced in the 1990s, after a media studies professor at Fordham University named Edward Wachtel visited several famous caves in southern France, including Lascaux, Font-de-Gaume, Les Combarelles, and La Mouthe. Wachtel was puzzled by what he called "spaghetti lines" on the drawings, partially obscuring them. There were also images of an ibex with two heads, or a bull drawing superimposed over the drawing of a deer.

Inspiration struck when the local farmer serving as his guide swung the lantern inside the cave. The color schemes shifted, and the engraved lines seemed to animate. Wachtel subsequently published a paper entitled, "The First Picture Show: Cinematic Aspects of Cave Art," in which he concluded that the cave drawings were meant to be perceived in three dimensions—one of them being time.

Wachtel's ideas are admittedly speculative, albeit intriguing, given the lack of archaeological context for these ancient settings. But Needham and others in the field are combining established methods—such as micro- and macroscopic analysis and 3D modeling—with experimental archaeological and virtual reality modeling to reconstruct the conditions of this Paleolithic period in hopes of learning more.

For instance, last year, we reported on how a team of Spanish scientists conducted in situ experiments with three different kinds of Paleolithic lighting sources in the hopes of discovering what those various illumination methods might tell us about the emergence of "human symbolic and artistic behavior" in the form of cave art. The team conducted their experiments at the Isuntza 1 Cave in Spain's Basque country.

They chose two distinctive spaces—a large, wide chamber and a smaller chamber, connected by a rough passage—and performed eight experiments involving torches, stone lamps with animal fat, and a small fireplace. Their measurements showed that the various lighting sources had very different characteristics and, thus, were probably used in different contexts. The Spanish team also built a virtual 3D model to examine the lighting conditions of a section of the Atxurra Cave known as the Ledge of the Horses, which boasts two panels of about 50 animal engravings: bison, goats, horses, and hinds, many of them overlapping.

Their findings had no direct bearing on Wachtel's speculation about prehistoric cinematic art. But the scientists argued that the more archaeologists learn about Paleolithic lighting sources, the more we will understand about how those lighting sources affect human perception in a cave environment, with implications for the emergence of cave art.

The plaquettes at the Montastruc rock shelter

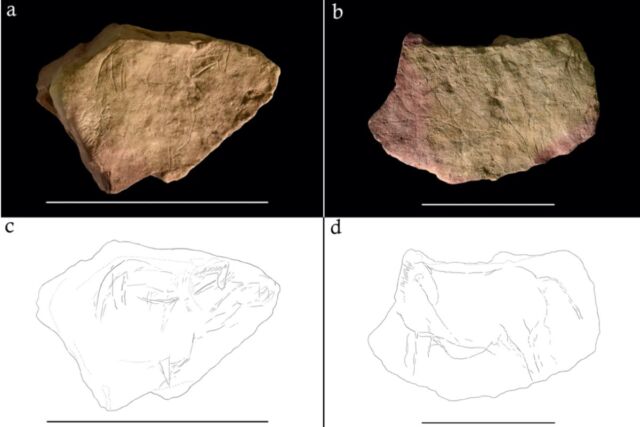

This latest study focuses on the carved stone plaquettes rather than cave art, but both involve mingling complex surfaces, engraved forms, and shifting light. De l'Isle found his artifacts in what's now known as the Montastruc rock shelter. (Rock shelters are shallow cave-like openings in the bases of bluffs or cliffs, often favored by prehistoric people as living spaces.) Those artifacts—including stone tools, harpoons, personal ornaments, and 54 limestone planquettes—are now housed in the British Museum in London. Most of the planquettes measure about 10 to 20 centimeters (roughly 4 to 8 inches) long and wide, and are engraved on both sides with animal images.

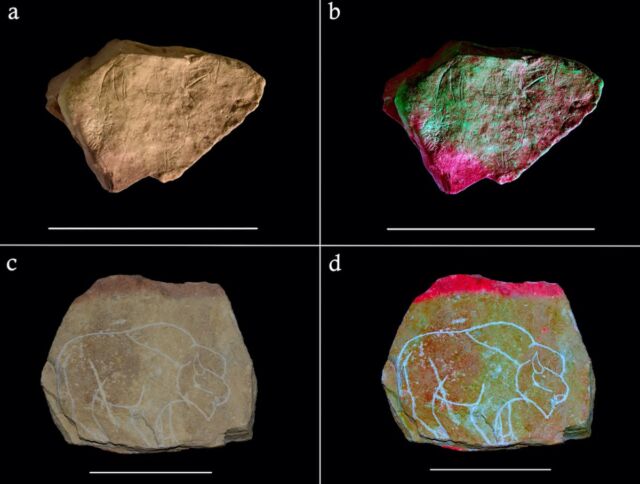

Archaeologists don't know much about how these plaquettes may have been used, but Needham et al. were intrigued by the evidence of exposure to heat, such as bands of pink discoloration (rubefaction), cracking, thermal fractures, and pot lids on the 50 planquettes made of limestone. The four non-limestone plaquettes showed no such traces. They also noted that the engravings were placed in such a way as to incorporate the block's shape and natural cracks and undulations.

Furthermore, "Where engravings on plaquettes were super-imposed, a similar approach was adopted," the authors wrote. "Rather than ignoring or engraving over previous depictions, animals were often melded together or fitted around each other, and sometimes body parts were recycled." For instance, in one sample, the abdomen and neck of a horse engraving form the back and neck of a cow, with the horse's head forming the ear of the cow.

Experimenting with heat

The heating traces suggested that the limestone plaquettes may have been uniquely associated with fireside hearths. The rubefaction is due to the reaction of iron impurities in the limestone during heating; this kind of dramatic color change has also been observed in the limestone walls of the Chauvet cave. So Needham and his colleagues hypothesized that the limestone plaquettes had been subjected to relatively high temperatures between 250-300 degrees Celsius. (When heated above 350 degrees Celsius, the pink coloration changes to a grayish hue.)

Limestone plaquettes would be well-suited for lining a hearth, given how effectively the material transfers and radiates heat. To test their hypotheses, Needham et al. created replica limestone plaquettes and conducted several experiments under varying conditions involving heat. They took high-resolution photographs of these experiments and used digital imaging software to better visualize the rubefaction and gray discoloration.

Virtual reality supports conclusions

The replicas were not an exact match for the original artifacts, but the authors said their findings were primarily used to develop virtual reality models to simulate Paleolithic conditions, in order to capture the visual effects of how flickering firelight from a virtual hearth might have interacted with the engravings. They surmised that the heating of the limestone plaquettes may have been deliberate, but not intended for any functional purpose. Rather, it was meant to animate the engravings as a form of Paleolithic entertainment.

The VR simulations supported that hypothesis, and the animation effects were particularly strong with those plaquettes with superimposed engravings. For instance, with plaquette 691, "The flickering light source draws focus of one engraved horse form and then another, giving the impression that the figures are moving across the plaquette's surface," the authors wrote.

So that superposition may have been intentional on the part of the artists, who sought to capture those animating effects. "Hearths can be social settings, and the presence of plaquettes alongside objects used in daily life at Montastruc indicates they may have been used in these social contexts by the fireside," the authors concluded. The results suggest that these stones "were engraved and positioned by hearths where properties of the limestone material, the engraved forms, and firelight entwine to create visceral visual experience within what may have been a rich and active nighttime socio-cultural setting."

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0266146 (About DOIs).

Listing image by Needham et al., 2022, PLOS ONE/CC-BY 4.0

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.