People tend to associate intelligence with brain size. And as a general guideline, this makes sense: more brain cells, more mental capabilities. Humans, and many of the other animals we’ve come to think of as unusually bright, such as chimpanzees and dolphins, all have large brains. And it’s long been assumed that the smallest brains simply don’t have the capacity to support complex mental processes. But what if they do?

The vast majority of Earth’s animal species are rather small, and a vanishingly small portion of them have been studied at all, much less by cognition researchers. But the profile of one group of diminutive animals is rapidly rising as scientists discover surprisingly sophisticated behaviors among them.

“There is this general idea that probably spiders are too small, that you need some kind of a critical mass of brain tissue to be able to perform complex behaviors,” says arachnologist and evolutionary biologist Dimitar Dimitrov of the University Museum of Bergen in Norway. “But I think spiders are one case where this general idea is challenged. Some small things are actually capable of doing very complex stuff.”

Behaviors that can be described as “cognitive,” as opposed to automatic responses, could be fairly common among spiders, says Dimitrov, coauthor of a study on spider diversity published in the 2021 Annual Review of Entomology. From orb weavers that adjust the way they build their webs based on the type of prey they are catching to ghost spiders that can learn to associate a reward with the smell of vanilla, there’s more going on in spider brains than they commonly get credit for.

“It’s not so much the size of the brain that matters, but what the animal can do with what it’s got,” says arachnologist Fiona Cross of the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Cross studies the behavior of jumping spiders, the undisputed champs of cognition among spiders. Although these tiny arachnids have brains that could literally fit on the head of a pin, the work of Cross and other scientists suggests that they have capabilities we’d have no problem hailing as signs of intelligence if exhibited by animals with much larger brains, like dogs or human toddlers.

“Jumping spiders are remarkably clever animals,” says visual ecologist Nathan Morehouse, who studies the spiders at the University of Cincinnati. “I always find it delightful when something like a humble jumping spider punctures our sense of biological superiority.”

One possible reason jumping spiders are so behaviorally advanced is that they have the sharpest vision known for animals their size, which is typically just 1 millimeter to 2.3 centimeters in length. They use this visual prowess to find, stalk, and pounce on their prey, rather than the better-known spider strategy of building a web and waiting for a meal to arrive.

“Their vision has emancipated them, leading them to be able to explore an environment,” says animal behavior researcher Ximena Nelson, who also studies jumping spiders, in her lab at the University of Canterbury. Being out and about in the world, they need to be able to see things—predators, prey, mates—from afar and make decisions before approaching them. “In my view, that’s what has led to their pretty remarkable cognition.”

Spiders play mind games

The jumping spiders shown to have the sharpest eyesight and the most impressive smarts belong to the genus Portia, found in Africa, Asia, and Australia. These spiders prefer to hunt other spiders and have strategies tailored to each species they prey upon. Renowned University of Canterbury jumping spider researcher Robert Jackson has discovered that many of Portia’s tactics are quite devious.

When hunting another group of jumping spiders called Euryattus, Jackson reports, Portia employs a clever trick. Euryattus females build nests in curled-up dead leaves suspended in air by silk attached to rocks or vegetation. Courting males crawl down the silk suspension ropes, stand on top of the nest, and shake it in a specific way. The signal draws the female out of the nest. Portia appears to take advantage of this system by mimicking the male’s shake and luring the female into an ambush.

For Portia, finding the right strategy is especially important when pursuing spiders that also eat jumping spiders. To attack a web-building spider, for example, Portia deceives the spider into moving closer by plucking some of the silk strands of its web. If the target spider is relatively small, Portia plucks the web to mimic a trapped insect, prompting the spider to rush over and think it’s about to have a meal—only to become one instead. But if the resident spider is bigger and potentially more dangerous, Portia may instead create a gentle disturbance similar to a fruit fly contacting a single strand at the edge of the web that the spider will slowly wander over to inspect. As soon as the target is close enough, Portia pounces and strikes with venomous fangs.

If these strategies don’t work on a particular web spider, another of Portia’s tricks is to shake the whole web so it moves as if a gust of wind had hit it. This acts as a smokescreen for the vibration Portia makes as it crawls into the target spider’s web. In laboratory experiments, Jackson found that Portia will try different plucking methods, speeds, and patterns until it finds just the right combination to fool each individual web spider it hunts—essentially learning on the job.

“Even amongst this surprisingly intelligent group, Portia stand out as being oddly brilliant,” Morehouse says. “They are, after all, hunting very dangerous prey, so caution and cleverness are useful tools.”

Spiders make plans

One of the most fascinating aspects of Portia’s hunting strategy is that it often involves spotting prey from a distance and then planning out an elaborate route to get to it. Jackson first observed this in the wild when Portia encountered a species of orb weaver that defends its web by violently shaking it, tossing any invading jumping spiders to the forest floor. Instead of entering the web, Portia navigated a roundabout path to find a better position from which to attack. “In that context, it was better for Portia to take the detour, go around the tree trunk, go up above the spider, go down on a line of silk, and swing in, grab the spider in its web without even touching the silk,” Cross says.

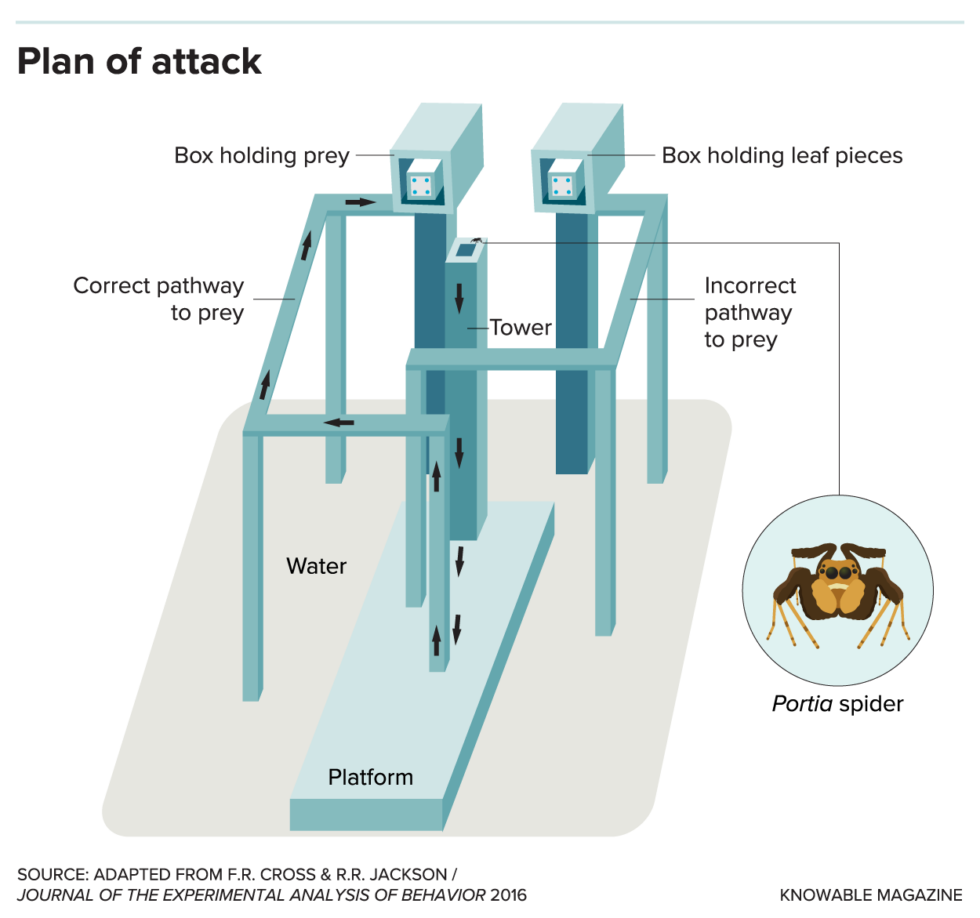

To find out how these itsy-bitsy spiders map out such complicated routes, Cross and Jackson put Portia’s mental abilities to the test in the laboratory. They built an apparatus with a central viewing tower on a platform, surrounded by water, from which a spider can see two other towers topped with boxes: one containing dead spiders that Portia likes to prey on, and one with dead leaves. The only way to reach the prey without getting wet, which jumping spiders loathe, is to climb down onto the platform and then choose the correct one of two separate walkways leading to the boxes.

From the perch atop the viewing tower, the spiders carefully surveyed the scene before descending the tower and climbing up a walkway. Most spiders chose the path that led to the meal, even if this meant moving away from the prey and passing the incorrect walkway on the way. Cross and Jackson argue that the spiders planned the route from the viewing tower and then followed it, possibly by forming a mental “representation” of the scene—an impressive cognitive feat for a brain barely bigger than a poppy-seed.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.