Spoiler alert: The company still has a massive amount of work to do to reach the Moon.

The stupefying and stupendous capture of a Starship rocket earlier this month by two mechanical arms marked a significant step forward in SpaceX’s efforts to forever alter humanity’s relationship with the heavens.

Yet as remarkable as the rocket catch was, it represents but a single step on a long path. SpaceX seeks to make launch cheap, frequent, and reliable with Starship, and the company is working toward a day when rockets are routinely caught by the launch tower, set back on a launch mount, refueled, and flown again within hours. SpaceX says these efforts will one day culminate in Starships landing on the Moon and Mars.

Critics of the Starship architecture say it is inefficient because of the mass refueling that must occur in low-Earth orbit for the spacecraft to travel anywhere. For example, fully topping off a Starship that can land humans on the Moon and return them to lunar orbit may take a dozen or more tanker flights. But this only seems stupidly impractical under the old space paradigm, in which launch is expensive, scarce, and unreliable. Such criticism seems less salient if we imagine SpaceX reaching the point of launching a dozen Starships a week or more in a few years.

The capture of a Super Heavy booster on October 13 at the company’s Starbase facility in South Texas brings us closer to such a higher flight rate. It validated the wild concept of a launch tower that not only supports a rocket before liftoff but then has the wherewithal to grab it minutes later. Even two years ago, this idea sounded outlandish, but no longer. SpaceX proved its titanic booster does not need cumbersome landing legs and can eliminate days of processing time otherwise needed to move a landed rocket back to the launch site. Less mass and shorter turnarounds are huge wins for Starship.

So what’s next?

Here’s our best attempt to piece together the milestones and major goals of the Starship program over the next several years before it unlocks the capability to land humans on the Moon for NASA’s Artemis Program and begins flying demonstration missions to Mars. For fun, we’ve also included some estimated dates for each of these milestones. These represent our best guesses, and they’re almost certainly wrong.

In-flight Raptor re-light (late 2024, early 2025)

To date, the Starship upper stage of the Super Heavy rocket has yet to fly an orbital trajectory. Instead, the second stage was lost during the first three flights before making a controlled reentry into the Indian Ocean on the fourth and fifth test flights of the vehicle, including the launch earlier this month.

The primary reason Starship has not gone into orbit and made multiple flights around the planet is that SpaceX (and the Federal Aviation Administration) want to be sure the vehicle is brought back to Earth safely and landed in a remote area of an ocean. Starship is very large, and chunks of the vehicle falling onto land, especially populated land, would be catastrophic. To make a controlled reentry, SpaceX must demonstrate the ability to relight the rocket’s Raptor engines in space for a precise deorbit burn.

During Starship’s third test flight in March 2024, SpaceX initially planned to conduct an in-flight relight of one or more of the Raptor engines, but this attempt was aborted as the vehicle spun out of control. On the last two test flights, SpaceX has not attempted a Raptor test as the engineering teams focused on improving the reentry capabilities of the second stage.

However, SpaceX may try to ignite one or more Raptor engines during the sixth test flight, or shortly thereafter. Successfully doing so would allow the company to begin flying orbital missions with Starship and likely open the way for Starlink launches, possibly as early as the first half of next year. These will be larger Starlink satellites that can only fit within Starship’s capacious payload and will provide direct-to-cell Internet capability.

SpaceX has already test-fired the Starship upper stage for this sixth test flight (known as Ship 31), and last week it rolled the Super Heavy first stage (Booster 13) to the launch site for a static fire test. From a hardware and regulatory standpoint, a launch of this test flight in November is very possible.

Return a Starship to terra firma (mid- to late 2025)

On the fifth test flight this month, SpaceX demonstrated the ability to land a Starship upper stage in a targeted area of the Indian Ocean. We know this because the company had a camera on a pre-positioned buoy track the rocket’s reentry and then subsequently released the footage.

The ability to precisely land Starship opens up the possibility of bringing a Starship back to land. SpaceX founder Elon Musk has mentioned “catching” a Starship in the first half of 2025, presumably with a tower in South Texas. (The company is not close to completing launch-and-catch towers anywhere else in the world). However, the regulatory issues surrounding the catch of a Starship at the Starbase facility in South Texas are, to put it mildly, interesting.

Unlike the Super Heavy booster, which flies over the Gulf of Mexico and only receives a green light to return to the coastal launch site seconds before a landing attempt, Starship would necessarily fly over Mexico (likely not far from the populous city of Monterrey) and Texas on its track to Starbase. You want to be quite sure big pieces of your spacecraft aren’t falling off when returning over land.

For this reason, SpaceX may attempt to vertically land Starship elsewhere first. There have been rumors about a partnership with Australia, and one source told Ars that SpaceX was scouting the Johnston Atoll in the Pacific Ocean earlier this year. Such locations would allow for a safer return of Starship to land. However, such an approach would also necessitate landing legs.

In the future, SpaceX will undoubtedly build multiple versions of Starship. The “tankers” used to deliver propellant to a large depot in low-Earth orbit won’t have legs because they will fly back to Texas or Florida to be caught by towers. But to land on the Moon or Mars, SpaceX will eventually need to add legs to the vehicle.

The question is whether SpaceX will undertake this leg-development project now to enable landing tests or push it back and navigate the regulatory thicket to enable Starship catches in South Texas. It’s possible that no final decision has been made yet.

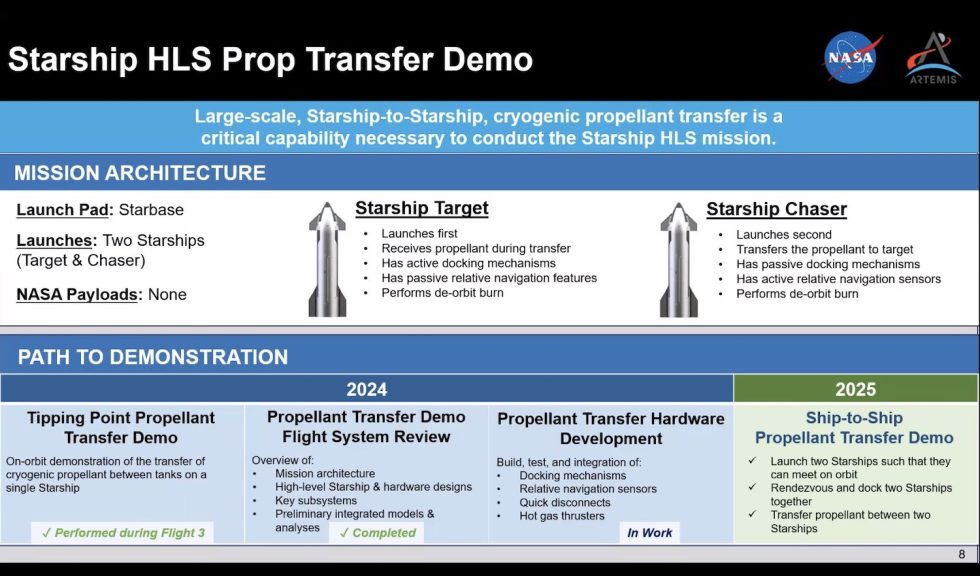

HLS prop-transfer demo (late 2025)

This is the next big milestone for NASA, which is eager to see the development of a Starship “Human Landing System” to facilitate its Artemis plan for the Moon. Publicly, the space agency is holding to a September 2026 date to land its first Artemis crew on the lunar surface. To reach that date, NASA officials have previously told Ars that SpaceX needs to fly a propellant-transfer test during the first quarter of 2025.

We don’t expect that to happen, as a lot of preparatory work needs to be completed before this test can occur.

For the propellant transfer demonstration, SpaceX will launch a Starship “target” into low-Earth orbit to be followed closely by a Starship “chaser.” The vehicles will then rendezvous in space, dock, and in an unprecedented space ballet, the chaser vehicle will transfer a significant amount of cryogenic propellant into the target vehicle. Finally, the ships will undock, and each will perform a deorbit burn.

Pulling off this demonstration mission will presumably require the completion of a second launch tower in South Texas for the chaser launch. In addition, SpaceX must build and test docking mechanisms, quick-disconnects, navigation sensors, and hot gas thrusters.

SpaceX works fast and has undoubtedly been pushing forward in many of these areas in the background. However, the company does not yet have a firm date for the test. Two sources told Ars that the company is targeting “next year” for the test, so optimistically, we're perhaps a year away from what will certainly be must-see TV. Regardless of the test outcome, it's probable that SpaceX will perform multiple versions of this test to optimize procedures.

Re-fly a Super Heavy first stage (early 2026)

SpaceX has now recovered the booster stage of its Starship rocket, and there can be no question that engineers are retrieving incredibly valuable data about the vehicle’s performance and the wear and tear on the hardware. This booster will not fly again, but one of the first stages caught in the coming months may very well fly a second time.

After this rocket catch this month, Musk commented on his social network, X, that there was a “good chance that Starship achieves full stack reusability in 2025, which is the critical breakthrough needed to make life multiplanetary.” This implies the company wants to re-fly both a booster and upper stage next year, but the timeline seems optimistic, especially for the Starship upper stage.

History may offer some better clues for what to expect. A little more than 15 months passed between the first time SpaceX landed a Falcon 9 rocket in December 2015 and the eventual reuse of a first stage in March 2017. The urgency is greater with Starship, and the company has vastly more resources to hand. At the same time, Super Heavy is a massively larger vehicle and more complex than the Falcon 9 rocket. I would expect SpaceX to take its time with fully testing a boost stage before putting it back on a launch tower, thereby limiting risks to its ground-based infrastructure.

SpaceX is also rapidly iterating on the design of its boosters, so the vehicles it lands today may not be ones it wants to re-fly, preferring to use improved models. For these reasons, a Super Heavy re-flight is probably at least a year away.

Ground systems and LOX

We're not putting a date on this one, as it will happen gradually over time. However, preparing the way for frequent Starship launches represents a significant hurdle over the next couple of years.

Musk has said that, initially, SpaceX plans to build two launch towers in South Texas and two in Florida. Presumably, this is the baseline ground infrastructure needed to support the Artemis Program and the multiple refueling flights needed to enable lunar touchdowns. SpaceX still has plenty of paperwork to process for this, in the form of working with the US Space Force in Florida and clearing environmental reviews with the Federal Aviation Administration to construct these four towers and reach a high cadence of launches.

Another major but unappreciated issue is commodities. At liftoff, the Super Heavy booster alone carries a mass of 7.5 million pounds (3,400 metric tons) of cryogenic propellant. Starship requires about a third as much. That sounds like a lot because it is. Liquid oxygen comprises a significant majority of this, and each launch puts a serious dent into the US production of liquid oxygen, which is used by various customers, including hospitals.

Put another way, launching four Starship rockets in a single day would consume all of the nation’s liquid oxygen capacity for that day. Accordingly, SpaceX must find a way to scale production of liquid oxygen, and ensure a tremendous supply to both South Texas and its future Starship launch facilities in Florida.

Long-duration flight test (late 2026)

NASA has consistently had this milestone on its Human Landing System schedule since the first versions of the timeline were released in August 2021. (At the time, the propellant transfer test was due to occur in the fourth quarter of 2022 and the long-duration flight test about six months later, so we’re running about three years behind).

Although the space agency has provided few details, this long-duration test is probably intended to demonstrate the ability of a Starship vehicle to loiter near the Moon.

This is necessary because, as part of the initial Artemis missions, NASA’s astronauts will launch inside an Orion spacecraft and rendezvous with Starship in lunar orbit days later. Due to potential weather and technical launch delays for NASA’s Space Launch System rocket, Starship is required to be able to loiter in lunar orbit for up to 100 days while waiting for the arrival of a crew. During this time, the ship must autonomously remain in a habitable condition and prevent significant boil-off of its liquid oxygen and methane propellants.

NASA and SpaceX will likely finalize the design of the “lunar” Starship vehicle after this flight test.

Uncrewed lunar landing (early-to-mid 2027)

This will be the most critical test of Starship before a lunar landing can take place. During this flight, a fully fueled Starship will depart from low-Earth orbit and travel to the Moon. There, after a certain period of time, it will be cleared to attempt a vertical landing near the South Pole of the Moon.

There are multiple challenges with such a landing, but one of the most significant is the potential for tipping. Starship needs a fairly flat surface to ensure that the vehicle does not topple over. (One source indicated to Ars that the lunar surface must be within 1.5 degrees of being perfectly flat). This mission will likely carry cargo that will be offloaded to test the “elevator” that astronauts will ride inside down to the surface of the Moon.

After a few days on the surface, Starship will enter the most critical part of its mission, the ascent off the lunar surface. The Apollo Lunar Module used storable, hypergolic propellants, Aerozine 50 and Nitrogen tetroxide, that did not need to be kept at cryogenic temperatures like methane and liquid oxygen. The challenge for Starship is that it must launch from the surface of the Moon without a tower or any ground support equipment. This will be the acid test for Starship’s viability as a lunar lander.

Depending on the level of success enjoyed by this test flight, SpaceX and NASA may feel the need to repeat it before the Artemis III lunar landing mission.

Crewed landing (September 2028)

If all goes well, it should be possible for NASA to fulfill the initial promise of the Artemis Program and land two astronauts on the surface of the Moon in 2028. This is two years later than NASA’s current goal of September 2026 but would still represent a herculean task by SpaceX and the space agency. If there are significant setbacks, such as failed tower catches or mishaps during fueling in space, the program will doubtlessly face more delays.

Naturally, some people might wonder why SpaceX and NASA are putting so much effort into a complex lunar lander when the Lunar Module developed and used in the 1960s was much simpler. It’s a fair question. The answer is this: Like the rest of the hardware used during the Apollo program, the mighty Saturn V rocket and the Apollo spacecraft, the Lunar Module was expended after a single use. It quickly became unaffordable for the United States to fly Apollo missions.

A top-level goal for NASA is to return to the Moon sustainably. Reuse of key elements of the architecture is essential for this. Moreover, the Apollo program lacked the capacity to deliver large pieces of hardware to the Moon. Even if the Lunar Module had been repurposed for cargo only, its maximum capacity was about 5 tons. An expendable Starship could carry an astonishing 200 tons inside its payload fairing to the lunar surface.

If we get this right, the United States really could have an amazing lunar program. But it will require a lot of hard work up front. Fortunately, Musk has turned all of the resources at SpaceX loose on this project. For the first time in the company’s history—during the entirety of which Musk has been ruthlessly cost-efficient—SpaceX is no longer constrained by funding. There is a long path yet to unlock the potential of Starship, but the engineers at SpaceX are going as fast as anyone can.

Hope you enjoyed this news post.

Thank you for appreciating my time and effort posting news every day for many years.

2023: Over 5,800 news posts | 2024 (till end of September): 4,292 news posts

RIP Matrix | Farewell my friend ![]()

- lurch234 and dabourzannan

-

2

2

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.