You can consider this the start of NASA's Falcon Heavy era. The launch of the Psyche asteroid mission this week is the opening act among five launches the space agency has directly reserved on SpaceX's heavy-lift rocket over the next few years.

These Falcon Heavy flights will cut across NASA's portfolio of robotic space missions, dispatching probes deep into the Solar System, deploying a flagship-class astronomical observatory, sending up a weather satellite, and launching the keystone to NASA's Gateway mini-space station around the Moon.

The launch of the Psyche asteroid explorer, scheduled for Thursday from Launch Complex 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, kicks it off. "We’ve been preparing for this for several years, and we’ve benefited from SpaceX's manifest. They’ve launched four Falcon Heavies since last November," said Tim Dunn, a NASA launch director based at the Florida spaceport.

All told, we know of up to 10 Falcon Heavy missions on contract with SpaceX. Five of those are firm contracts with NASA's Launch Services Program, an office that procures launch services for the agency's robotic space missions, matching payloads with commercial rockets. Notable on this list is Europa Clipper, a $5 billion mission led by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to explore Jupiter's icy moon Europa, an ocean world that may harbor environments conducive to life.

One of the Falcon Heavy rockets set to fly soon is for the US Space Force, and Astrobotic has booked two Falcon Heavy flights for commercial Moon landers that will carry NASA experiments to the lunar surface. There are two more Falcon Heavy bookings that SpaceX could use to launch resupply ships to the Gateway lunar station, perhaps in the late 2020s, although the status of those missions is unclear.

So it's fair to say NASA is involved—directly or indirectly—in driving demand for nine of the 10 Falcon Heavy missions currently in SpaceX's backlog.

“It’s an incredible capability for our nation. We’re fortunate to have it," Dunn told Ars in a recent interview. "If you look at the manifest, this is our first of a series of Falcon Heavies."

NASA's fearless commitment

Despite being overtaken by the recent debuts of NASA's Space Launch System and SpaceX's Starship mega-rocket, the Falcon Heavy is still the world's most powerful operational commercial rocket, capable of hauling nearly 64 metric tons (more than 140,000 pounds) of cargo into low-Earth orbit a couple hundred miles up if SpaceX expended all three of the rocket's first-stage boosters.

Setting aside propellant to recover the rocket's two side boosters eats into the Falcon Heavy's payload capacity, but the SpaceX heavy-lifter still outmatches any other rocket currently available to NASA. New rockets, like United Launch Alliance's Vulcan and Blue Origin's New Glenn, will come closer to Falcon Heavy's lift capability, but both launchers are unproven. ULA says it still has a chance to launch the first Vulcan test flight in December, and Blue Origin officials have said the New Glenn could debut next year. Those schedules could be generously described as optimistic.

The Falcon Heavy, meanwhile, is seven-for-seven since its inaugural launch in February 2018. It has launched commercial communications satellites and military payloads. The launch of NASA's Psyche mission will mark the eighth flight of a Falcon Heavy rocket. If schedules hold, SpaceX could launch a ninth Falcon Heavy mission at the end of November with a classified payload for the Space Force.

SpaceX usually recovers the side boosters from its Falcon Heavy rockets for reuse. But this won't be possible on at least two upcoming Falcon Heavy launches for NASA.

SpaceX

As of Monday, SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket, which uses a single first-stage booster, has flown 68 times this year. Now SpaceX is falling into a rhythm with launching the larger Falcon Heavy, which combines three modified Falcon 9 boosters into a single rocket.

"I’ve come to really appreciate a lot of what they have brought to the industry, continuing to push the envelope in a number of different ways," Dunn said of SpaceX. "I would hope that they would say something along the lines that they have appreciated the engagement, the analytical and engineering rigor that NASA brings to the equation. I know, on the analytical side, software reviews, some of the hardware issues we’ve worked with them over the years, there have been a lot of times where we’ve arrived at a mutual agreeable solution that both parties brought value to."

Earlier this year, NASA engineers formally certified the Falcon Heavy rocket to launch the agency's most expensive robotic missions, according to Dunn. This level of certification is known as Category 3 in NASA parlance, requiring a minimum of three successful flights of a common launch vehicle configuration in addition to deep insight by NASA engineers into a rocket's design and a launch contractor's quality control processes. If a launch company eschewed this extensive government involvement, they would need to fly their launcher on 14 consecutive successful missions.

You can read more about NASA's launch vehicle certification requirements in this procurement document.

NASA previously certified ULA's Delta IV, Atlas V, and SpaceX's Falcon 9 rockets at the Category 3 level. ULA's Vulcan and Blue Origin's New Glenn launchers will need to fly successfully at least three times before becoming eligible to launch NASA's most critical science payloads (the Space Force and ULA agreed on a plan to certify Vulcan for national security missions after two successful missions).

In this 2021 presentation, a manager in NASA's Launch Services Program suggested that, on average, the third successful launch of a common launch vehicle configuration is delayed nearly three years from a contractor's prediction a year ahead of the rocket's first flight. That's about where Blue Origin says it is right now with New Glenn, while ULA's Vulcan rocket appears significantly closer to its first flight.

The bottom line is that NASA is likely several years away from certifying Vulcan or New Glenn to launch missions in the same class as Psyche or Europa Clipper.

This leaves SpaceX as the only option to launch many of NASA's science missions. United Launch Alliance's Atlas V and Delta IV rockets are nearing retirement, with all of ULA's remaining inventory sold to other customers. With Vulcan still years away from NASA certification, ULA has temporarily stopped bidding on NASA launch service procurements.

For nearly a decade, ULA was the sole launch provider for NASA's medium and large science missions, from the company's formation in 2006 until the launch of a NASA-sponsored oceanography satellite on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket in 2016. This period without competition resulted in higher launch prices for NASA, which had to direct a higher percentage of each mission's budget toward buying a rocket instead of adding to a spacecraft's scientific capability.

Rising prices evermore?

The arrival of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets helped reverse the upward trend in NASA launch prices. In 2020, NASA awarded a $117 million launch contract to SpaceX for a Falcon Heavy launch of Psyche. Then, in 2021, NASA selected a Falcon Heavy rocket to launch Europa Clipper, a contract valued at $178 million. Later in 2021, NASA purchased a Falcon Heavy launch at $152 million for a large, new NOAA weather satellite.

For the Europa Clipper launch, SpaceX will need to dispose of all three Falcon Heavy boosters to give the spacecraft enough of a boost away from Earth. This is something for which SpaceX typically charges an additional fee.

The 27 Merlin engines on SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket as it completes preparations for launch of NASA's Psyche asteroid mission.

SpaceX

SpaceX's dominant position in the global launch market has concerned some industry officials and analysts, who worry a SpaceX launch failure might disrupt the business plans of a wide range of customers. Some officials also worry SpaceX might raise launch prices as it surveys the launch market and sees a lack of competition.

Commercial customers usually don't disclose how much they pay for launch services, but the monetary value of NASA's launch contracts is part of the public record. While we've seen little change in how much SpaceX is charging NASA for Falcon 9 launch services, the NASA price for Falcon Heavy has gone up.

It's important to note that launch prices for NASA and military payloads run higher than SpaceX's base commercial price. Government satellites often require special handling, and NASA and the Space Force pay for bells and whistles like engineering insight, unique cleanliness specifications, and in some cases, schedule priority over other commercial missions.

Two of NASA's missions on Falcon Heavy come with especially stringent requirements. One of those is the launch of the first two elements of NASA's Gateway lunar outpost on a single Falcon Heavy rocket. These two modules, a power and propulsion element and a pressurized habitat for astronauts, are projected to weigh in at about 18 metric tons (nearly 40,000 pounds). That would make this spacecraft the heaviest payload SpaceX has ever launched.

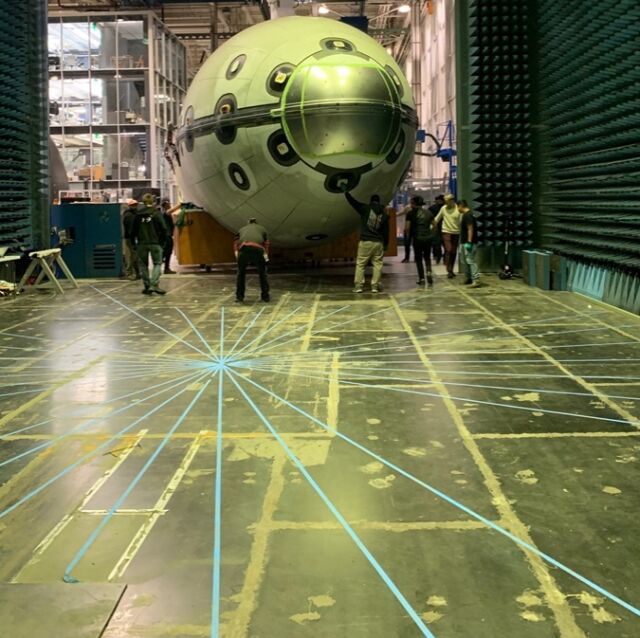

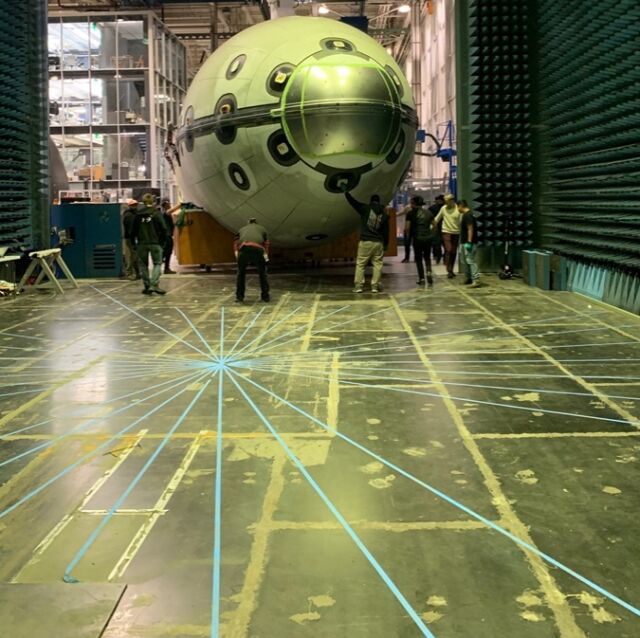

SpaceX is developing an extended payload shroud to accommodate the large size of the Gateway modules, which won't fit into a standard SpaceX fairing. A test unit of the extended payload fairing is undergoing tests this year inside the world's largest vacuum chamber at a NASA facility in Ohio to ensure it's ready for the Gateway launch, now scheduled for the end of 2025.

NASA's $332 million Falcon Heavy launch contract for the first two Gateway modules is more than double what SpaceX charged NASA for the launch of Psyche. But it covers more than the Falcon Heavy launch itself. It includes SpaceX's fee to dispose of the Falcon Heavy boosters and also pays for some of the development costs for the new fairing design. “We’ve got a lot of engineering and analytical effort devoted to that extended fairing right now," Dunn said.

SpaceX's extended payload fairing undergoing tests at NASA's Neil Armstrong Test Facility in Ohio.

NASA/SpaceX

Last year, NASA announced a $255 million launch order for a Falcon Heavy mission to haul the agency's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope into space. This wide-view observatory is the next in NASA's most exclusive family of space-based telescopes, following up on Hubble and Webb.

The price for the launch of the Roman telescope is also significantly higher than SpaceX's rate for Psyche and Europa Clipper. At the time of the contract award, a NASA spokesperson said the Roman telescope would launch inside SpaceX's standard payload fairing, not the extended shroud designed for the Gateway modules. However, Roman will require strict cleanliness protocols to ensure its sensitive optics remain unblemished during pre-launch preparations, provisions that would at least partially explain the higher launch price.

If you want a Falcon Heavy, speak now

NASA and the Space Force will surely buy more Falcon Heavy launches from SpaceX. The military and the US government's spy satellite agency see the Falcon Heavy as a partial replacement—alongside ULA's yet-to-debut Vulcan—for the Delta IV Heavy rocket, which has lofted top-secret surveillance missions into orbit for the better part of two decades.

But traditional commercial satellite operators, the types of companies who regularly buy Falcon 9 launches, haven't been as gung-ho about Falcon Heavy. Three of the seven Falcon Heavy missions to date have carried large commercial communications satellites toward positions in geostationary orbit, a location favored by many conventional satellite operators working in the video and television broadcast markets.

But there are no such missions currently in SpaceX's Falcon Heavy backlog. In fact, the London-based commercial communications satellite company Inmarsat had a contract option to launch one of its payloads on a Falcon Heavy rocket but decided instead to launch the spacecraft on a Falcon 9 earlier this year.

One reason commercial customers (outside of lunar landers) have not signed up for many Falcon Heavy launches appears to be that the Falcon 9 is just so damn good. SpaceX may be a victim of its own success here. With a predictable launch cadence and a fleet of reusable boosters on the shelf, the Falcon 9 flies multiple times per week and can take off from three different launch pads, while the triple-body Falcon Heavy is currently limited to one launch site.

"I will always remember my first time actually seeing the Falcon 9 up close," Dunn said. "In my mind, I had thought Falcon 9 was going to be a nice cute replacement for Delta II (a now-retired medium-lift rocket from ULA), until you see it, and you realize how large the rocket is. Then you put three of those cores side by side, and it’s very impressive."

SpaceX has introduced upgraded versions of the Falcon 9 rocket and experimented with higher throttle settings to eke out more performance. The owners of commercial communications satellites have also been willing to load more fuel on their spacecraft to allow them to launch into a lower orbit on a cheaper Falcon 9, instead of deploying into a more optimized orbit on a more costly Falcon Heavy. The extra fuel on the satellite can overcome the difference with additional orbit-raising maneuvers, a process that can add several weeks or months to the time until the spacecraft begins operational service.

Eventually, SpaceX wants to retire the entire Falcon rocket family in favor of the even larger Starship rocket. But Starship is still a long way from achieving NASA certification.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.