We have no explanations for this sort of slow repeat.

On Wednesday, researchers announced the discovery of a new astronomical enigma. The new object, GPM J1839–10, behaves a bit like a pulsar, sending out regular bursts of radio energy. But the physics that drives pulsars means that they'd stop emitting if they slowed down too much, and almost every pulsar we know of blinks at least once per minute.

GPM J1839–10 takes 22 minutes between pulses. We have no idea what kind of physics or what kind of objects can power that.

A persistent transient

GPM J1839–10 was discovered in a search of the galactic plane for transient objects—something that's not there when you first look, but appears the next time you check. The typical explanation for a transient object is something like a supernova, where a major event gives something an immense boost in brightness. They're found at the radio end of the spectrum, fast radio bursts, but are also very brief and, so, fairly difficult to spot.

In any case, GPM J1839–10 showed up in the search in a rather unusual way: It showed up as a transient item twice in the same night of observation. Rather than delivering a short burst of immense energy, such as a fast radio burst, GPM J1839–10 was much lower energy and spread out over a 30-second-long burst.

Follow-on observations showed that the object repeated pretty regularly, with a periodicity of about 1,320 seconds (more commonly known as 22 minutes). There's a window of about 400 seconds centered on that periodicity, and a burst can appear anywhere within the window and will last anywhere from 30 to 300 seconds. While active, the intensity of GPM J1839–10 can vary, with lots of sub-bursts within the main signal. Occasionally, a window will also go by without any bursts.

A search through archival data showed that signals had been detected at the site as far back as 1988. So, whatever is producing this signal is not really a transient, in the sense that the phenomenon that's producing these bursts isn't a one-time-only event.

The list of known objects that can produce this sort of behavior is short and consists of precisely zero items.

A bad fit for anything

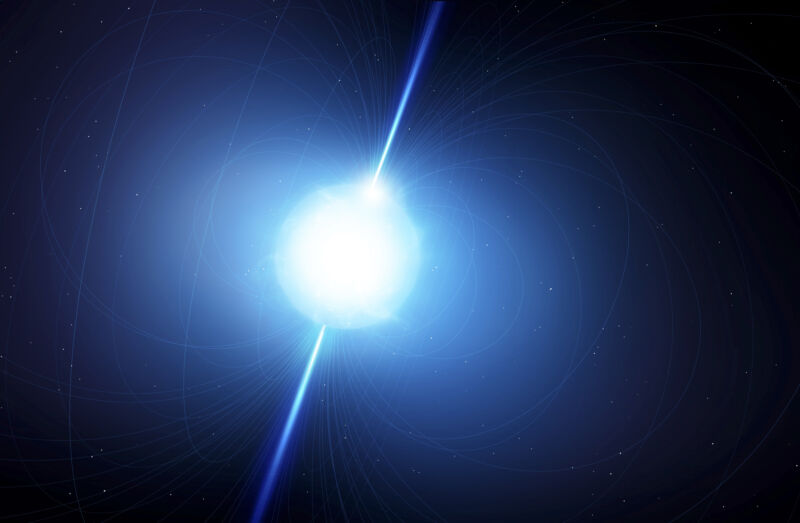

The most obvious analog for GPM J1839–10 is a pulsar, a rapidly spinning, magnetized neutron star. These objects release radio energy at their magnetic poles, which may not be lined up with their axis of rotation. As a result, the star's rotation can sweep the poles across the line of sight to Earth, creating the perception of a flash of radio waves each time one of the magnetic poles aligns with Earth.

But the flashes of pulsars repeat quickly, with a gap between them of anywhere from around a minute down to milliseconds. And, more significantly, physics dictates the gap has to be quick. The magnetic field that powers the production of radio waves is generated through the star's rotation. If it starts rotating too slowly, then the magnetic field will drop to a point where it can no longer generate significant radio emissions. In other words, if it slows down, it goes dark, which is why we don't see any that take much more than a minute between pulses.

That doesn't rule out neutron stars, though. Another option involving them is the magnetar, a neutron star with an intense magnetic field that's prone to energetic outbursts. But those outbursts also generate more energetic photons, and the researchers checked the site of GPM J1839–10 with an X-ray telescope and saw nothing. Plus, magnetars are thought to rotate more quickly than the 22-minute gap implies, so they're probably out as well.

Another alternative is a white dwarf with an unusually strong magnetic field. These are much larger objects, and so take a lot longer than a neutron star to rotate. But we've observed thousands of them within the Milky Way and haven't seen anything like this. There's only one with periodic emissions, and it outputs far less energy than GPM J1839–10.

Even if we expand the list of potential sources to include other objects we don't understand, we still come up short. The same team had identified another slow-repeating radio transient, GLEAM-X J162759.5-523504.3, a few years earlier. But it was only active for about two months before fading from sight—a far cry from the 35 years that GPM J1839–10 has been bursting.

What now?

So, given that every possible explanation is terrible, where do we go from here? The good news is that these objects will be so difficult to spot that it's possible there are a lot more out there that we've overlooked. The bad news is that they're still hard to spot. The length of the burst—up to 300 seconds—and the gap between bursts mean short-cadence observations will likely either see something there the whole time or miss it entirely.

We'd really need to have hardware stare at a single area of space for a half-hour or more, and to have its staring divided up into multiple exposures, to be sure we catch it in both its on and off states. And that involves a major commitment of hardware.

In the meantime, we can potentially narrow down the location of GPM J1839–10 to try to see if there's anything interesting in other wavelengths. Since this is located within the galactic plane, however, that's going to be challenging as well.

Nature, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06202-5 (About DOIs).

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.