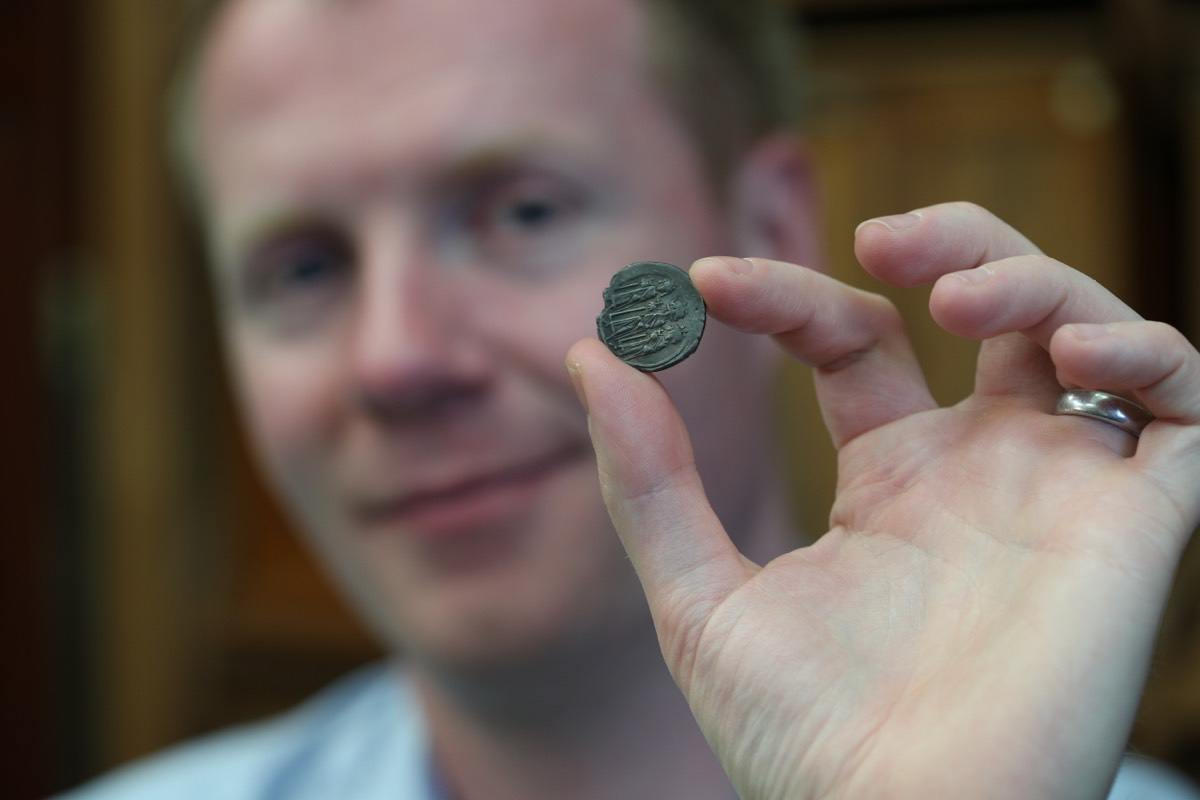

A selection of the Fitzwilliam Museum coins that were studied, including coins of Charlemagne and Offa.

The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Sometime around 660 CE, silver coinage replaced gold as the dominant form of currency in northwest Europe. But what was the source of all that silver? According to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity, silver for the earlier post-Roman coins during this period came from Byzantine silver plate, while silver for the later coins most likely came from mines located in Melle, Aquitaine.

“This was such an exciting discovery," said co-author Rory Naismith, a medieval historian at the University of Cambridge. "I proposed Byzantine origins a decade ago but couldn’t prove it. Now we have the first archaeometric confirmation that Byzantine silver was the dominant source behind the great seventh-century surge in minting and trade around the North Sea.”

There are a number of high-tech tools that can be used to learn more about historic currencies. For instance, Michael Wiescher, a nuclear physicist at the University of Notre Dame, has combined XRF scaling with PIXE mapping of Roman denarii to test the currency's quality and learn more about the production techniques. Working with his undergraduate students, he has also used electron spectroscopy to measure the silver content of each coin and learn about how the impurities were distributed.

The Roman silver denarius was the backbone currency of the Roman Empire between 200 BCE and 300 CE. During Nero's reign, the coins were required to be 92.5 percent silver to protect the currency against inflation and devaluation. But the analysis of coins from 250 to 350 CE showed declining percentages of silver because the Roman mints gradually debased the denarius to increase their profits. By 295 CE, the silver content was just about 5 percent. Wiescher's analysis revealed that most of the coins are composed of silver and copper and that sulfur and iron impurities led to corrosion in some of them.

The same trick of replacing some of the silver in coins with copper showed up again thousands of years later in Spain's Latin American colonies. Wiescher analyzed 91 silver rials dated between the 16th and 18th centuries, from Mexico and Potosi, Bolivia.

Between 1645 and 1648, the silver content dropped from 92.5 percent sterling to just 70–80 percent; the rest was a copper admixture. When this was discovered in the 17th century, the silver market in Spain crashed and the coins were devalued, with devastating effects on the colonial Spanish economy. Some of that silver from Spain and Mexico eventually made its way to the early American colonies. The Boston Mint used Spanish silver between 1653 and 1686 for minting coins, once again adding a little copper or iron to increase their profits.

In 2022, scientists used a variety of physics-based methods—classic light microscopy, ultraviolet imaging, scanning electron microscopy, and reflection mode Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy—to analyze a cache of Roman coins that was discovered in Transylvania in 1713. Several bore the portrait of a Roman emperor named Sponsian and hence were thought to be forgeries, since there are no historical records of a Roman emperor with that name.

The 2022 analysis suggested the coins were probably genuine, speculating that Sponsian may have been an obscure Roman military commander in the Roman province of Dacia, an isolated gold mining outpost that overlaps with modern-day Romania. Given their mining resources, Dacia could have minted their own coins with Sponsian's image, which would have helped cement his authority and maintain economic stability and social order until the area was finally evacuated between 271 and 275 CE.

For this latest study, the coinage in question is the silver currency that came on the scene around 660 CE, which marked "a major transformation in the early medieval economy," according to the authors. Historians have long debated where the silver for that coinage came from. Did people melt down Roman plate and/or recycle Roman scrap metal? Was it imported from the Byzantine, as Naismith argued in 2012? Or was there a revival in silver mining around this time in medieval Europe, particularly in Melle in western France?

“There has been speculation that the silver came from Melle in France, or from an unknown mine, or that it could have been melted down church silver," said Naismith. "But there wasn't any hard evidence to tell us one way or the other, so we set out to find it.”

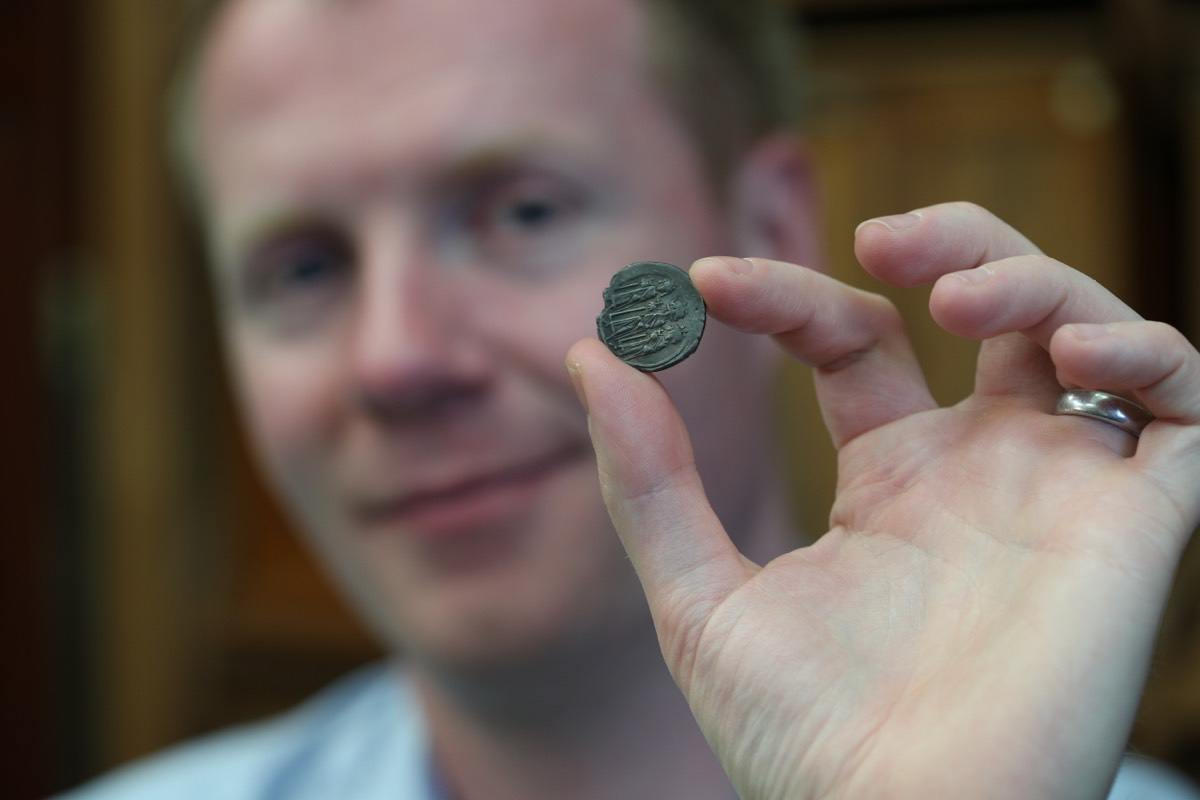

Rory Naismith holding a Byzantine silver coin in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Adam Page

Prior work had tested coins and artifacts from Melle silver mines, but less attention had been paid to coins minted in England, the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France. Naismith et al. used a combination of lead isotope and trace element analysis to study 49 medieval silver pennies and denarii from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. For the lead isotope analysis, they relied on a new technique called "portable laser ablation" to collect microscopic samples onto Teflon filters—a less invasive approach than traditional methods while maintaining high precision.

As one might expect, most of the coins contained silver. It was the respective amounts of gold, bismuth, and other elements that provided clues to the origin of the silver used in the coins. Per Naismith et al., 29 of the earlier coins (dated between 660 and 750 CE) showed chemical and isotopic signatures consistent with Byzantine silver from the third and early seventh centuries, including between 0.6 and 2 percent gold. There is no known European ore source matching those signatures, which are also not consistent with late Western Roman silver coins. This provides evidence of international trade relations between modern-day France, the Netherlands, and England.

Naismith points out that high-ranking people in England and Francia at this time possessed a great deal of silver artifacts, as evidenced by the significant cache of Byzantine discovered at Sutton Hoo. He estimates that this cache alone, had it been melted down, would have produced some 10,000 early pennies.

“These beautiful prestige objects would only have been melted down when a king or lord urgently needed lots of cash," said co-author Jane Kershaw of the University of Oxford. "Something big would have been happening, a big social change. This was quantitative easing, elites were liquidating resources and pouring more and more money into circulation. It would have had a big impact on people’s lives. There would have been more thinking about money and more activity with money involving a far larger portion of society than before.”

The remaining 20 coins analyzed for the study dated to a later period between 750 and 820 CE. This silver had substantially lower amounts of gold (in some cases, less than 0.01 percent), consistent with silver mined at Melle. The older, now debased silver was likely captured and refined for re-minting, combined with newer silver from Melle.

Naismith et al. suggest that Charlemagne was behind the shift to silver from Melle, citing records from the 860s in which King Charles the Bald (grandson of Charlemagne) decided to reform his kingdom's coinage and provided the mints with some silver to get the process going. Charlemagne may have done something similar, providing silver sourced from Melle to his mints. "It was only following the major reform of coinage by Charlemagne in 792–793 that coins from all surveyed mints showed a strong shift toward Melle-like silver," the authors concluded.

Antiquity, 2024. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.33 (About DOIs).

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.