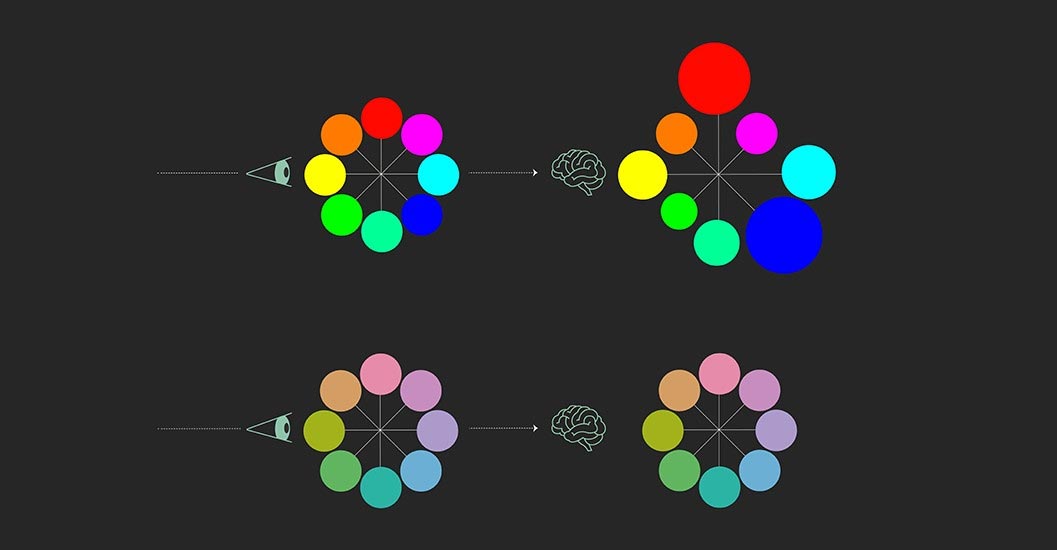

Humans perceive color when photoreceptor cells, the so-called cones, are activated in the retina. They respond to light stimuli by converting them into electrical signals, which are then transmitted to the brain. If maximally colored colors are selected in the RGB color space, the brain reacts with gamma oscillations to different degrees (upper row). The bottom row shows colors that activate the retinal cones to the same extent and create equally strong gamma oscillations in the brain. Credit: © ESI/C. Kernberger

Red has a signaling and warning effect. How is this color specificity reflected in the brain?

Scientists at the Ernst Strüngmann Institute for Neuroscience have now investigated the question of whether red triggers brain waves more strongly than other colors.

A red traffic light makes us stop. Because of their color, we immediately spot ripe cherries on a tree. The color red is attributed a signaling and warning effect. However, is this also reflected in the brain? Researchers at the Ernst Strüngmann Institute (ESI) for Neuroscience have now investigated this question. They wanted to know whether red triggers brain waves more strongly than other colors.

The new research focuses on the early visual cortex, also known as V1. It is the largest visual area in the brain and the first to receive input from the retina. When this area is stimulated by strong and spatially homogeneous images, brain waves (oscillations) arise at a specific frequency called the gamma band (30-80 Hz). But not all images generate this effect to the same extent. The study, by Benjamin J. Stauch, Alina Peter, Isabelle Ehrlich, Zora Nolte, and ESI director Pascal Fries was published earlier this year in the journal eLife.

Brain anatomy illustration.

Color is hard to define

“Recently, a lot of research has attempted to explore which specific input drives gamma waves,” explains Benjamin J. Stauch, first author of the study. “One visual input seems to be colored surfaces. Especially if they are red. Researchers interpreted this to mean that red is evolutionarily special to the visual system because, for example, fruits are often red.”

But how can the effect of color be scientifically proven? Or refuted? After all, it is difficult to define a color objectively, and it is equally difficult to compare colors between different studies. Every computer monitor reproduces a color differently, so red on one screen is not the same as on another. Additionally, there are a variety of ways to define colors: based on a single monitor, perceptual judgments, or based on what their input does to the human retina.

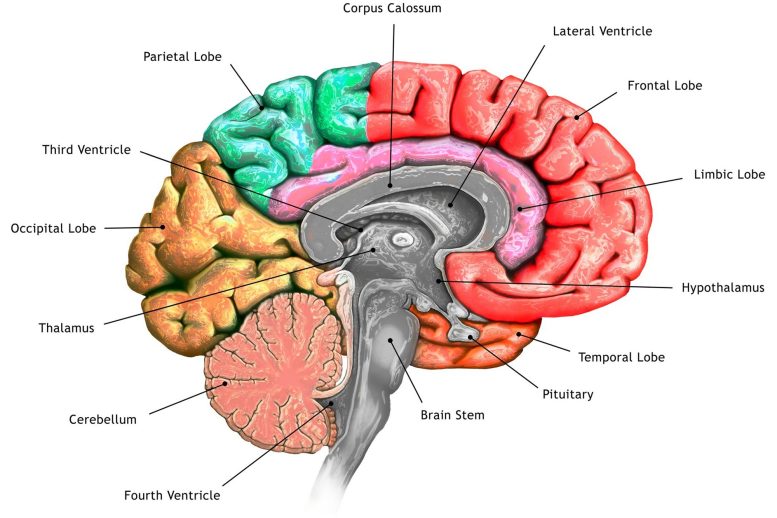

The visual cortex is the primary cortical region of the brain that receives, integrates, and processes visual information relayed from the retinas. It is located in the occipital lobe of the primary cerebral cortex, which is in the most posterior region of the brain.

The visual cortex is divided into five different areas, called V1 to V5, based on function and structure. Visual information from the retinas that are traveling to the visual cortex first passes through the thalamus, where it synapses in a nucleus called the lateral geniculate. This information then leaves the lateral geniculate and travels to V1, the first area of the visual cortex. V1, which centers around the calcarine sulcus, is also known as the primary visual cortex.

Colors activate photoreceptor cells

Humans perceive color when photoreceptor cells, the so-called cones, are activated in the retina. They respond to light stimuli by converting them into electrical signals, which are then transmitted to the brain. To recognize colors, we need several types of cones. Each type is particularly receptive to a specific range of wavelengths: red (L cones), green (M cones), or blue (S cones). The brain then compares how strongly the respective cones have reacted and deduces a color impression.

It works similarly for all human beings. It would therefore be possible to define colors objectively by measuring how strongly they activate the different retinal cones. Scientific studies with macaques have shown that the early primate visual system has two color axes based on these cones: the L-M axis compares red to green, and the S – (L+M) axis is yellow to violet. “We believe that a color coordinate system based on these two axes is the right one to define colors when researchers want to explore the strength of gamma oscillations. It defines colors according to how strongly and in what way they activate the early visual system,” Benjamin J. Stauch says. Because previous work on color-related gamma oscillations has mostly been run with small samples of a few primates or human participants, but the spectra of cone activation can vary genetically from individual to individual, he and his team wanted to measure a larger sample of individuals (N = 30).

Red and green have equal effect

In doing so, Benjamin J. Stauch and his team investigated whether the color red is something special and whether this color causes stronger gamma oscillations than green of comparable color intensity (i.e., cone contrast). And a side question was: Can color-induced gamma oscillations also be detected by magnetoencephalography, a method for measuring the magnetic activities of the brain?

They conclude that the color red is not particularly strong in terms of the strength of the gamma oscillations it induces. Rather, red and green produce equally strong gamma oscillations in the early visual cortex at the same absolute L-M cone contrast. Moreover, color-induced gamma waves can be measured in human magnetoencephalography when treated carefully, so future research could follow the 3R principles for animal experiments (Reduce, Replace, Refine) by using humans rather than nonhuman primates.

Colors that activate only the S-cone (blue) generally appear to elicit only weak neuronal responses in the early visual cortex. To some extent, this is to be expected, since the S-cone is less common in the primate retina, evolutionarily older, and more sluggish.

Development of visual prostheses

The results of this study led by ESI scientists, understanding how the early human visual cortex encodes images, may one day be used to help develop visual prostheses. These prostheses may attempt to activate the visual cortex to induce vision-like perceptual effects in people with damaged retinas. However, this goal is still a long way off. Before, much more needs to be understood about the specific responses of the visual cortex to visual input.

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.