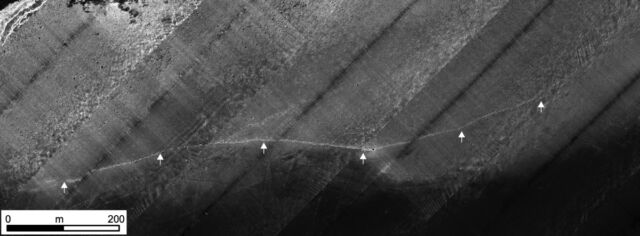

In 2021, Jacob Geersen, a geophysicist with the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research in the German port town of Warnemünde, took his students on a training exercise along the Baltic coast. They used a multibeam sonar system to map the seafloor about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) offshore. Analyzing the resulting images back in the lab, Geersen noticed a strange structure that did not seem like it would have occurred naturally.

Further investigation led to the conclusion that this was a manmade megastructure built some 11,000 years ago to channel reindeer herds as a hunting strategy. Dubbed the "Blinkerwall," it's quite possibly the oldest such megastructure yet discovered, according to a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—although precisely dating these kinds of archaeological structures is notoriously challenging.

As previously reported, during the 1920s, aerial photographs revealed the presence of large kite-shaped stone wall mega-structures in deserts in Asia and the Middle East that most archaeologists believe were used to herd and trap wild animals. More than 6,000 of these "desert kites" have been identified as of 2018, although very few have been excavated. Last year, archaeologists found two stone engravings—one in Jordan, the other in Saudi Arabia—that they believe represent the oldest architectural plans for these desert kites.

However, these kinds of megastructures are almost unknown in Europe, according to Geersen et al., because they simply didn't survive the ensuing millennia. But the Baltic Sea basins, which incorporate the Bay of Mecklenburg where Geersen made his momentous discovery, are known to harbor a dense population of submerged archaeological sites that are remarkably well-preserved—like the Blinkerwall.

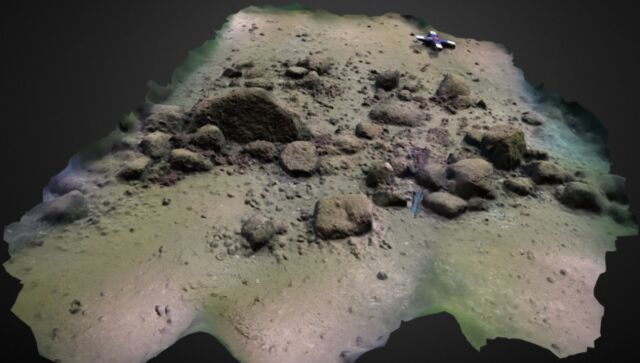

After they first spotted the underwater wall, Geeren enlisted several colleagues to lower a camera down to the structure. The images revealed a neat row of stones forming a wall under 1 meter (3.2 feet) in height. There are 10 large stones weighing several tons, spaced at intervals, and connected by more than 1,600 smaller stones (less than 100 kilograms or 220 pounds). "Overall, the ten heaviest stones are all located within regions where the stonewall changes is strike direction," the authors wrote. The length of the wall is 971 meters (a little over half a mile).

They concluded that the wall didn't form through natural processes like a moving glacier or a tsunami, especially given the careful placement of the larger stones wherever the wall zigs or zags. It is more likely the structure is manmade and built over 10,000 years ago, although the lack of other archaeological evidence like stone tools or other artifacts makes dating the site difficult. They reasoned that before then, the region would have been covered in a sheet of ice. The immediate vicinity would have had plenty of stones laying about to build the Blinkerwall. Rising sea levels then submerged the structure until it was rediscovered in the 21st century. This would make the Blinkerwall among the oldest and largest Stone Age megastructures in Europe.

As for why the wall was built, Geeren et al. suggest that it was used as a desert kite similar to those found in Asia and the Middle East. There are usually two walls in a desert kite, forming a V shape, but the Blinkerwall happens to run along what was once a lake. Herding reindeer into the lake would have slowed the animals, making them easier to hunt. It's also possible that there is a second wall hidden underneath the sediment on the seafloor. “When you chase the animals, they follow these structures, they don’t attempt to jump over them,” Geersen told The Guardian. “The idea would be to create an artificial bottleneck with a second wall or with the lake shore.”

A similar submerged stone-walled drive lane, known as "Drop 45," is located in Lake Huron in the US; divers found various lithic artifacts around the drive lane, usually in circular spots that could have served as hunting blinds. The authors suggest that the larger blocks of the Blinkerwall could also have been hunting blinds, although further archaeological surveys will be needed to test this hypothesis.

“I think the case is well made for the wall as an artificial structure built to channel movements of migratory reindeer,” archaeologist Geoff Bailey of the University of York, who is not a co-author on the paper, told New Scientist. Vincent Gaffney of the University of Bradford concurred. "Such a find suggests that extensive prehistoric hunting landscapes may survive in a manner previously only seen in the Great Lakes,” he said. “This has very great implications for areas of the coastal shelves which were previously habitable.”

PNAS, 2024. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2312008121 (About DOIs).

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.