Scientists are alarmed as sea surface temperatures stubbornly maintain record-breaking highs for more than a month, pushing the state of Earth's oceans into uncharted territory.

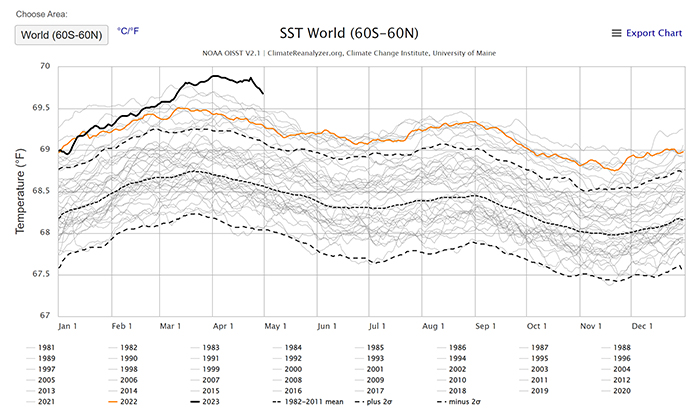

Starting in mid-March, data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) leaps dramatically from earlier recordings, following lows of both Arctic and Antarctic sea ice this year.

Dark line shows the current year. (climatereanalyzer.org)

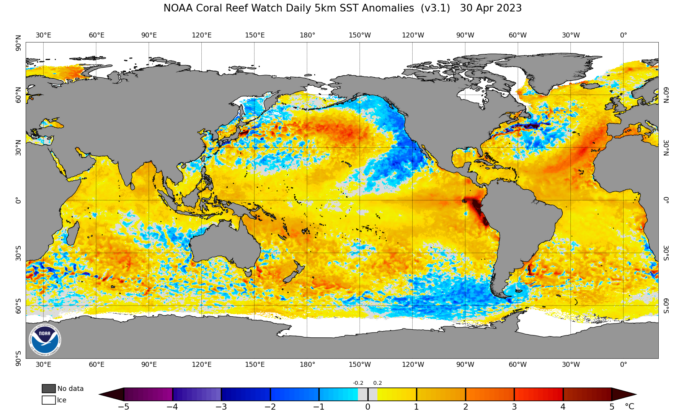

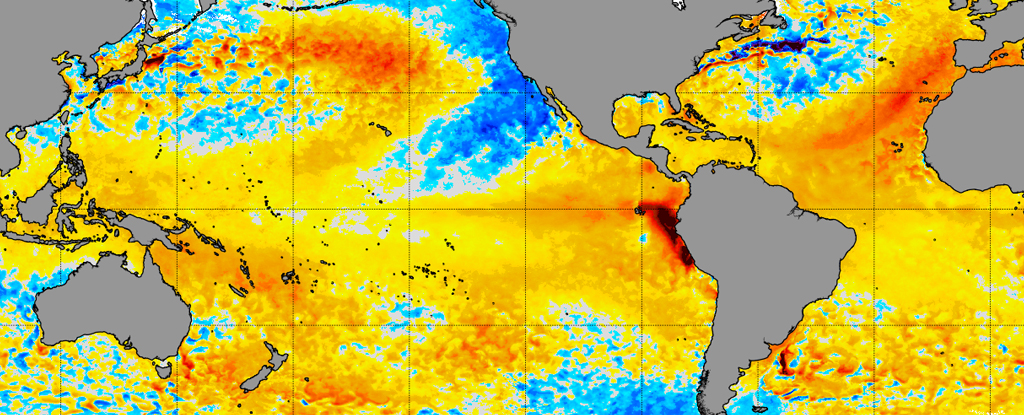

As a consequence, a large number of ocean heat waves are emerging around the globe, putting untold pressure on wildlife.

The events are alarming, but sadly not unexpected for those working in climate sciences.

"While it is comforting to see that the models work, it is terrifying, of course, to see climate change happening in real life," explains WHOI biogeochemist Jens Terhaar. "We are in it and it is just the beginning."

The previous temperature record was in 2016, during an El Niño – a climate pattern that further warms the oceans. While there's growing evidence that we'll soon be entering just such an event, we're not there quite yet, making it likely that sea surface temperatures may rise even further over the next year.

Heat gathering off the east coast of Chile tends to predict El Niños and that's exactly what we're witnessing at the moment.

Chart of sea surface temperature anomalies. (NOAA)

"If a new El Niño comes on top of it, we will probably have additional global warming of 0.2 to 0.25 °C," Potsdam Institute for Climate Research Earth systems scientist Josef Ludescher told the BBC.

The extra heat from an El Niño event would nudge some areas of our planet past 1.5 °C of warming for the first time, oceanographer Moninya Roughan explains for The Conversation.

Roughan believes what we're seeing is the easing of La Niña, which has brought brings cooler conditions that mask the extra heat in our planet's systems. However, some scientists are so worried and stressed by the possible implications they're reluctant to speak out.

As retired mathematician Eliot Jacobson explains on Twitter, the certainty of the shifted ocean temperature signal is unsettling.

Sigma probabilities are used to calculate the likelihood that the data in question is the result of something other than the hypothesis. We often report on this statistic in our physics and astrophysics articles, and 5 sigma is the threshold at which researchers are really confident that what they're seeing isn't merely the chaos of the Universe at work.

To put it another way, five sigma means there's a 99.99972 percent likelihood that the numbers are a measure of a predicted phenomenon, even if it happens to be a highly anomalous one.

Researchers fear that such a certain, anomalously large deviation from previous temperatures would indicate our oceans have reached the limits of their heat-absorbing capacity. This would be extremely bad news given our oceans have so far absorbed over 90 percent of the excess heat we've pumped into our climate systems.

"The cause for concern is that if it carries on, this will be well ahead of the climate curve [predicted] for the ocean," oceanographer Mike Meredith of the British Antarctic Survey told The Guardian. "But we don't know yet if that is going to happen."

So we're not quite there yet, but the trend follows last week's forecasts that we're currently on track for 3 °C of warming by 2100.

Still, it's important to remember that even if the ocean's heat storage limits are reached, everything we can do to reduce our harmful fossil fuel addiction still matters, perhaps even more so than ever.

As climate scientist Katharin Hayhoe has said in the past: "It's true some impacts are already here. Others are unavoidable. But my research, and that of hundreds of other scientists, clearly shows that our choices matter. It is not too late to avoid the worst impacts."

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.