Renaissance-era ice cream moulds, 500-year-old cookbooks, recipes meant only for popes: Rome's newest museum is a fascinating homage to Italy's history of food and cooking.

From the outside, the museum on Palatine Hill looked like just another of Rome's elegant palazzi, its entrance graced with statues of Roman soldiers and decorative urns.

Inside, however, it was clear that this wasn't your run-of-the-mill Roman mansion. Hundreds of culinary tools were displayed in glass cabinets: bulky 19th-Century pasta machines, 220-year-old Italian bowls once used by Italian monks and well-worn steel pots designed for making osso bucco, the classic northern Italian veal recipe. What at first looked like medieval plates of armour were in fact metal tray moulds up to 500 years old. Some were for baking, others for making chocolate or ice cream.

The Museo della Cucina displays instruments used for haute cuisine, pastries, chocolate, ice cream and baking (Credit: Ronan O’Connell)

Other displays held books. I stopped in front of one illustration to look at lumps of meat cooked over an open flame on a 16th-Century rotisserie; in the picture next to it, Italian men sat at a banquet table, eating. These sketches decorate the cover of one of the oldest cookbooks displayed in the museum, Il Trinciante, written in 1593 by Vincenzo Cervio. The author was a trinciante, or carver, for Italian Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. Cervio's 74-chapter opus reveals how to precisely cut fish, pies, fruits and vegetables and, above all, meat and fowl like pork, chicken, turkey, pheasant and peacock. Detailed drawings specify Cervio's preferred carving points to ensure juicy and flavourful cuts.

Il Trinciante is one of 120 cookbooks at the Museo della Cucina, a museum opening in May 2022 that will be the city's first focusing on the history of food and cooking. Since the first mass-printed cookbook was published almost 550 years ago, many Italian recipes have been all but lost, hibernating in old texts hidden in repositories, said the museum's director, Matteo Ghirighini. The Museo della Cucina aims to rectify that. Its collection is based on that of Italian chef Rosso Boscolo and includes many of the oldest and rarest cookbooks in existence – including some originally meant only for popes. Boscolo's Tuscan cooking school Campus Etoile Academy, meanwhile, will help the museum grow rare ingredients and perfect neglected recipes once reserved only for royalty.

When I got a sneak peek at the museum in November 2021, it was preparing for its launch. I came across it by accident. Rome is so awash with extraordinary sites that it's easy to overlook monumental churches and remains of 2,000-year-old palaces, let alone a yet-to-open cooking museum.

But already the Museo della Cucina had been included on Google Maps. And as I used my phone's GPS, I noticed its listing. What initially piqued my interest was its remarkable location. The museum is wedged between two of Rome's most important historic sites – the 2,600-year-old stadium Circus Maximus, and Palatine Hill, where Rome was founded and which is cloaked in the remains of ancient palaces and temples.

The Museo della Cucina is tucked between the Circus Maximus and Palatine Hill (Credit: Ronan O’Connell)

As it turns out, the museum isn't just on the Palatine but on the specific location where Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, were breastfed by the Roman wolf goddess Lupa more than 2,700 years ago. Myth has it that Romulus later established Rome on the same spot.

It is fitting the museum sits on such a historic location, said Ghirighini. "Cooking as a way of reading contemporary history has often been underrated," he said. "Cooking is a product of its time and it can tell us a lot about customs, ways of thinking, specific economic and political situations. So, a cookbook is often much more than it seems."

These sentiments were shared by Laila Tentoni, president of Italy's renowned Casa Artusi centre for gastronomy in Forlimpopoli, northern Italy. She said Italy's food revealed an enormous amount about the country's passions. And cookbooks, in turn, had greatly shaped the history and direction of Italian cuisine.

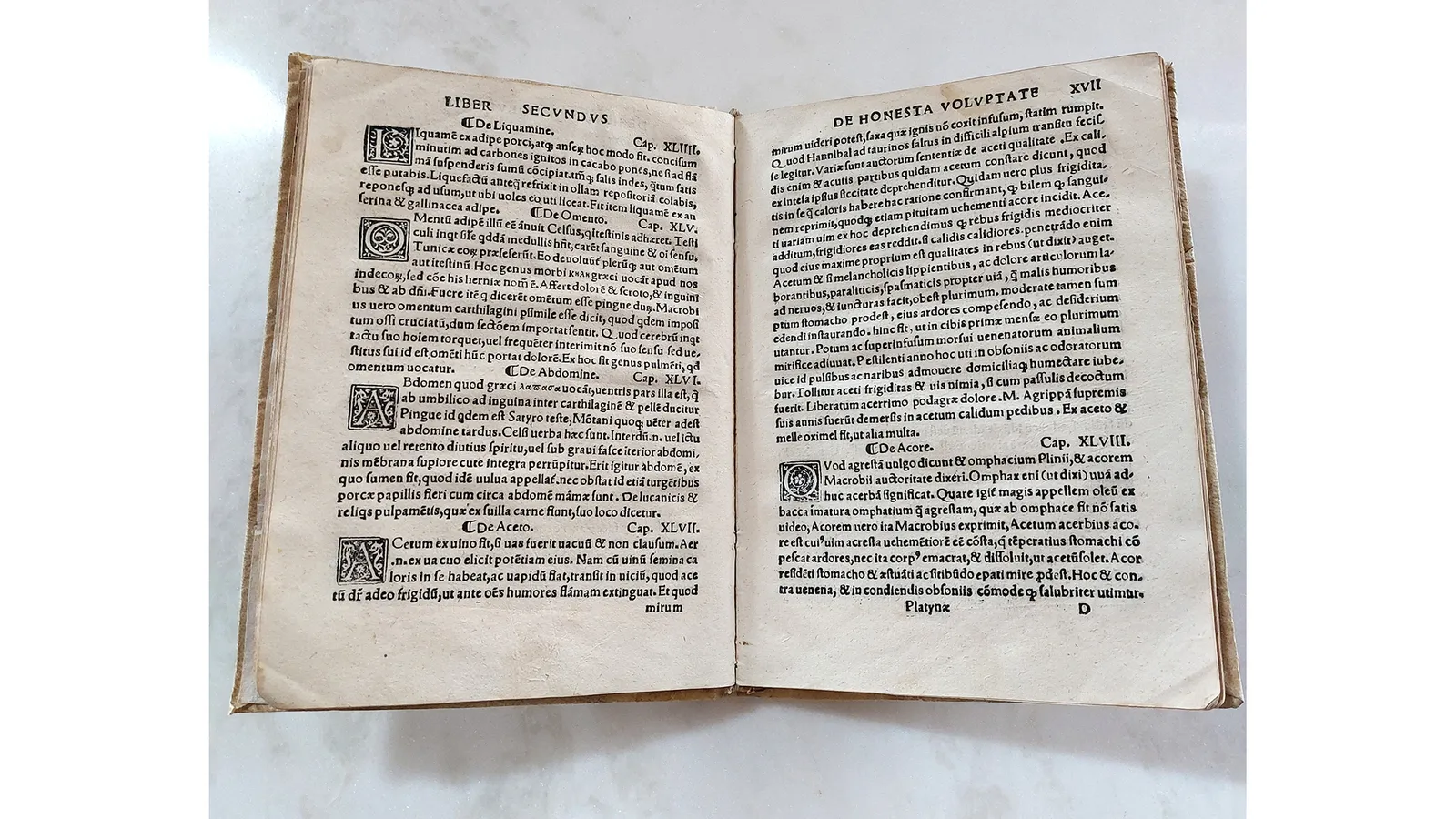

The museum displays the oldest mass-printed cookbook, Platina’s On Honourable Pleasure and Health (Credit: Museo della Cucina)

Casa Artusi is dedicated to one of the country's most revered cookbook authors, Pellegrino Artusi. Tentoni said Artusi's 1891 book, Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, aimed to demystify Italian cuisine that had previously been reserved for the country's elite.

"Artusi was like the first food blogger," Tentoni said. "Artusi suggests to be simple, to use local, seasonal and quality products. Always you must choose the finest ingredients as your raw materials, for these will make you shine, Artusi wrote."

I admired a rare first edition of Artusi's influential text on the second floor of the Museo della Cucina. While Artusi's cookbook is not as vibrantly illustrated as some others, it makes up for that with his colourful writing style. "Many people will read this recipe and cry out: 'Oh what a ridiculous pasta!'," he wrote about his curious Lentin Spaghetti, in an English language version of his publication I read online. Made from ground walnuts, breadcrumbs, confectioner's sugar and allspice – also known as Jamaican pepper or pimento – this sweet spaghetti was unfailingly popular with children, Artusi said.

Some of Artusi's recipes have since fallen out of favour – such as his recipe for eel pie. Not only is that long, slender fish difficult to prepare and cook – so much so that Japan has many specialist eel chefs – but Artusi's recipe pairs it with raisins, rosewater and almond milk.

Dozens of old cooking utensils are displayed at the Museo della Cucina (Credit: Ronan O’Connell)

Having long ago forgotten my high school Italian, I was unable to decipher the open pages of the library's books. But Ghirighini told me I could eventually read each one in English once the museum's comprehensive website is completed. "Basically, you have access to a full virtual, illustrated, guided tour through five centuries of gastronomy," he said.

From among that trove he singled out several texts I should examine. In addition to Artusi's classic, there was the first cookbook ever mass printed, On Honourable Pleasure and Health, by Italian author Bartolomeo Platina in 1474. That text, which focused on the preparation of single meals rather than decadent banquets, earned a huge following in Italy before its popularity saw it translated into French and German.

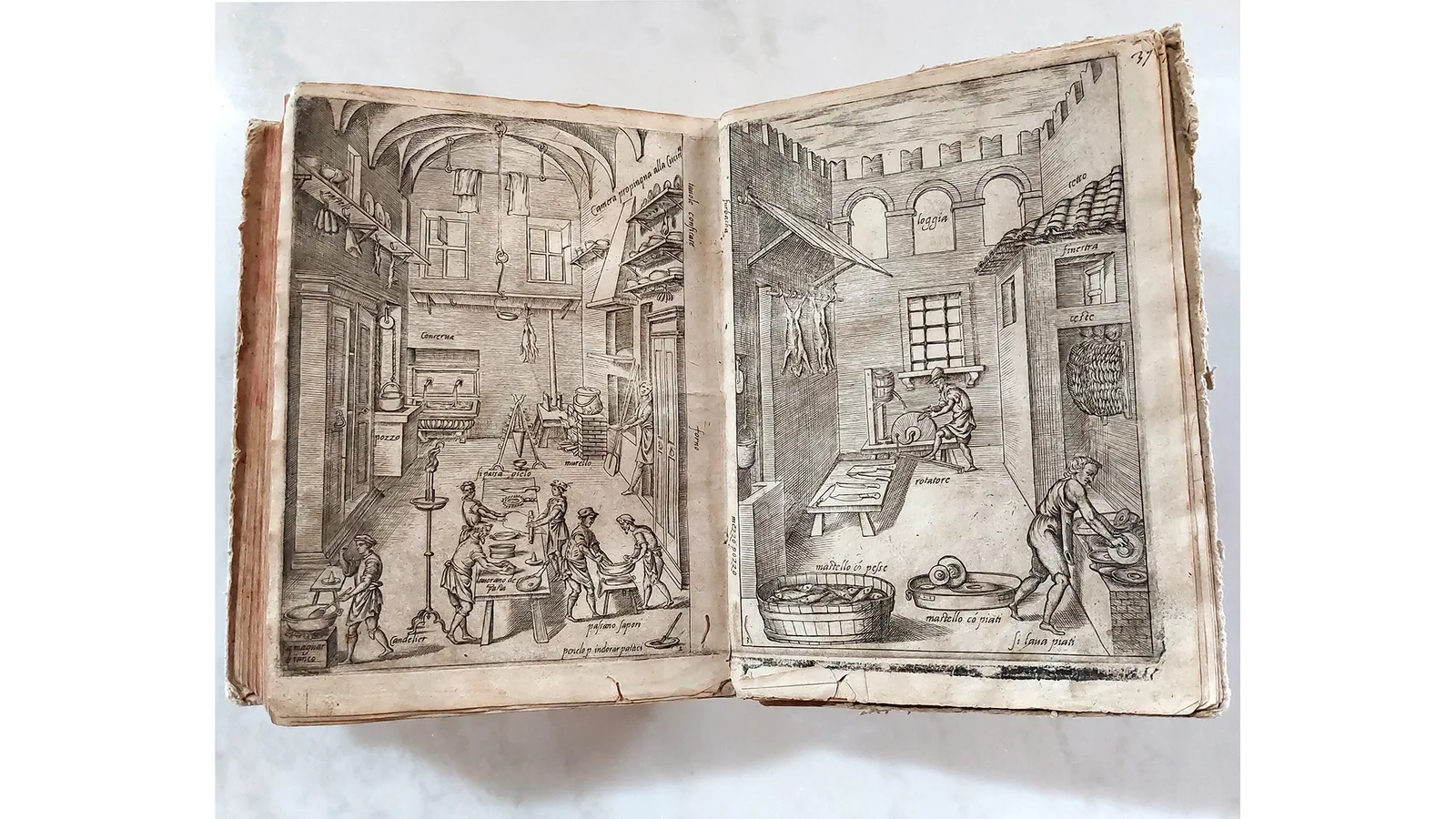

A similarly important cookbook, Ghirighini said, was The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi from 1570. That was written by and named after the revered Scappi, the private chef of Pope Pius V. This cookbook, which brims with sketches of meals being prepared in grand kitchens, was extraordinary because, for the first time, it gave the Italian public access to recipes previously untasted outside of the Vatican.

The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi, published in 1570, was written by the private chef of Pope Pius V (Credit: Museo della Cucina)

In particular, Scappi wrote of how Pope Pius IV was a fan of frog. Not just any frog, mind you, but those from the city of Bologna, which were especially plump and delicious. For the Pope, Scappi would remove the frogs' surprisingly large livers, coat them in egg, flour and milk and then fry them into crispy fritters. That was a snack.

The remainder of this amphibian was prepared as a heartier meal for His Holiness. Scappi would discard the head and the tips of the frog's feet, and fry what was left only in flour. Then he'd soak it in verjuice sauce made from unripened grapes, which was once a popular ingredient among Italian chefs but has largely been superseded by vinegar.

Because French cuisine had significant influences on northern Italian gastronomy – due to sharing both a border and mutual admiration for each other's continent-leading culinary prowess – the museum also displays many of France's finest cookbooks, written by the likes of Marie-Antoine Careme, Francois Massialot and Urbane Francois Dubois.

"The books in the museum contain the first printed recipes of all the most iconic dishes of the gastronomic culture of [Italy and France], from tomato sauce to supplì (rice croquettes) and panettone, from macarons to meringues," Ghirighini said.

As the owner of a sweet tooth, my mouth watered as I admired evocative drawings of towering cakes in Careme's book Le Patissier Royal Parisien. He pioneered a grandiose approach to cooking that leaned on spectacle as much as technique. From pastry, sugar and marzipan, Careme created giant replicas of famous buildings.

The museum exhibits an array of pudding moulds dating back to the 1700s (Credit: Ronan O’Connell)

Aside from books and artefacts, Ghirighini said the museum plans to bring historical dishes alive with tastings, such as the first-ever recipe for Italian tomato sauce, from the late 1600s. Taken from Antonio Latini's 1692 cookbook, this recipe has more in common with spicy salsa than the mild tomato sauce of the modern day thanks to its generous helping of fresh chillies.

There will also be on-site banquets featuring ancient recipes from the museum's cookbooks, some of which have been dormant for generations, although Ghirighini did not yet want to reveal yet what they may be.

"A cookbook and food museum in Rome is absolutely something new," said Flaminia Belloni, a Rome tour guide for 20 years. "It's a good chance to learn how the food and the cooking traditions were a real part of the lifestyle and state of mind for all Italians."

Ghirighini hopes others will agree. After all, few feats could be more difficult than attempting to crystallise, within one building, more than 500 years of Italian cooking – and doing justice to one of the most globally renowned, and fascinating, aspects of Italian culture.

- Karlston

-

1

1

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.