At a press conference shortly before NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft smashed into an asteroid, a reporter tried to get a sense of just what would happen as a bunch of metal and electronics smashed into a pile of rubble left over from the birth of the Solar System. "Give us a sense of this combat between our spacecraft and this rock," the reporter asked a scientist at the Applied Physics Lab.

"The spacecraft's going to lose," APL's Nancy Chabot quipped back.

The amazing thing about that loss is that we got to experience it in real time, as the last image from DART's onboard camera cut out after only a small fraction of it was transmitted to Earth.

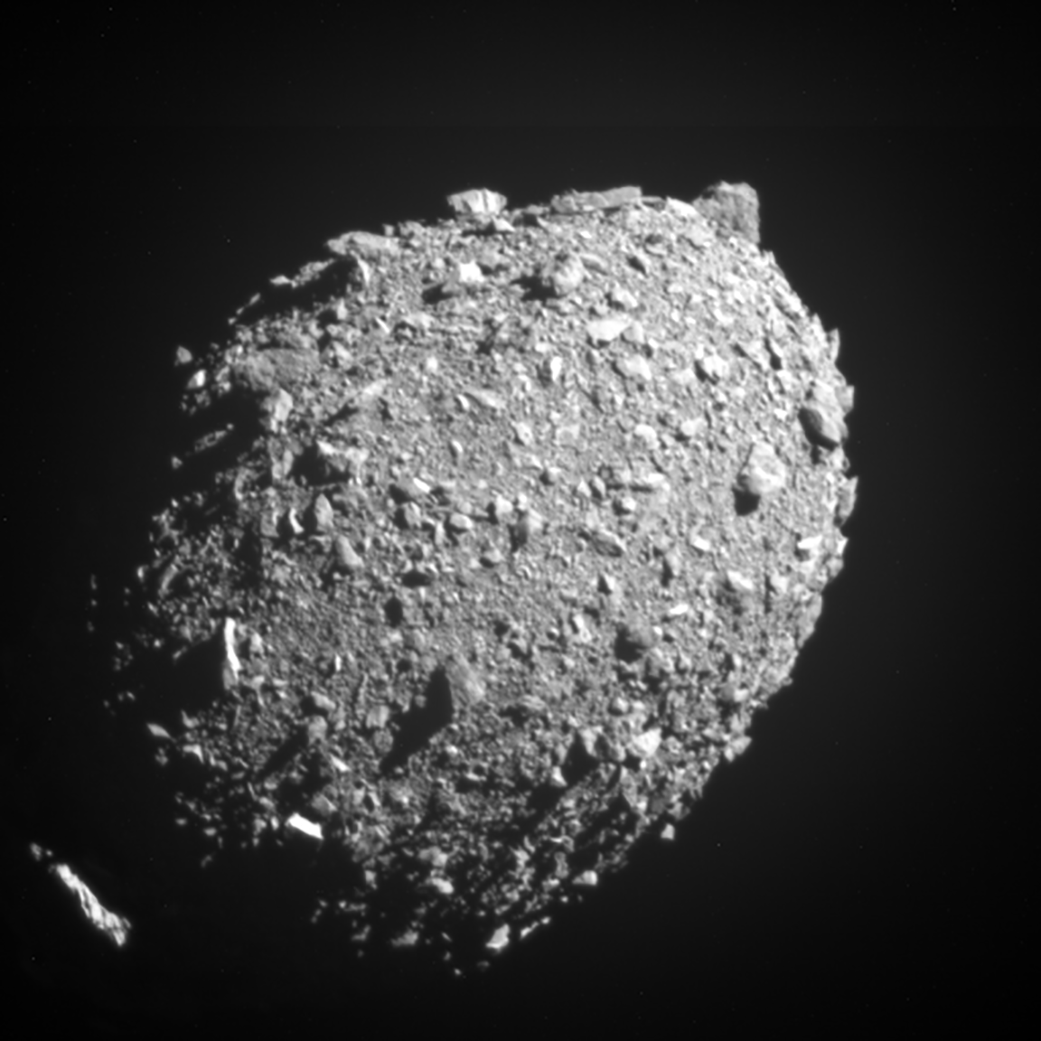

One of the last images taken that captures both objects in the Didymos system: Didymos and its smaller companion Dimorphos, the latter being DART's target

The last image where all of Dimorphos, DART's target, is visible.

The final image taken and transmitted by DART prior to its scheduled catastrophic disassembly.

The one that didn't quite make it, as transmission of the image data was disrupted by the destruction of all transmitting hardware.

Details of the spacecraft's crash landing/impact on the asteroid Dimorphos had to be captured on cameras that were quite a bit further from the point of impact. Many of those have now been made available, so we put together a collection of them and describe a bit about what you can see.

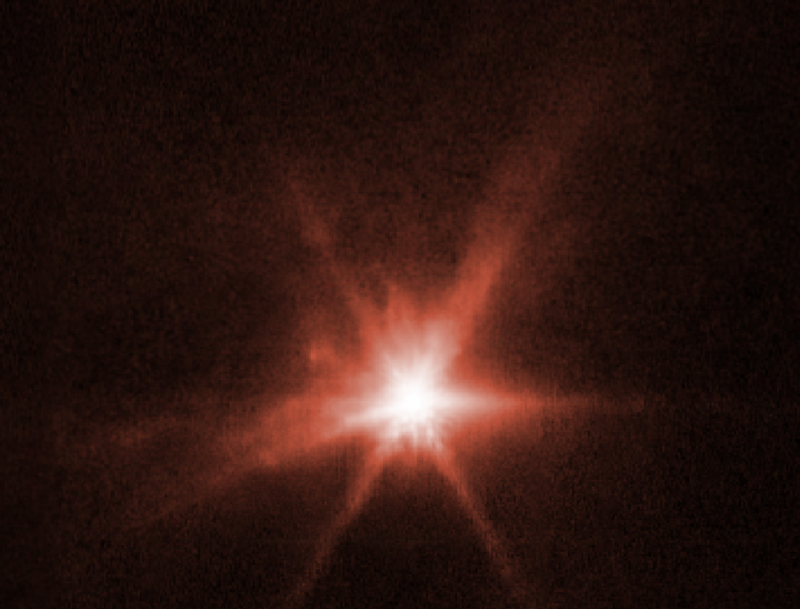

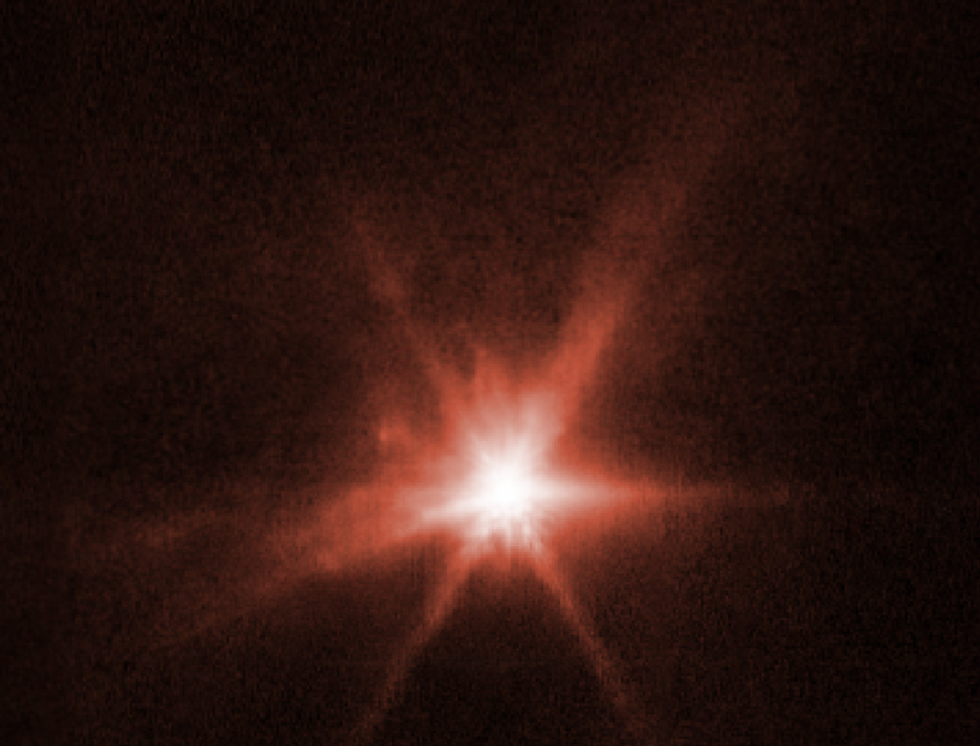

The closest cameras we had were on board LICIACube, a cubesat that was carried to space on board DART, and then separated a few weeks before impact. LICIACube had two onboard cameras (named Luke and Leia), one that does wide-field imaging, and one that can focus on details better. The Italian Space Agency, which ran the LICIACube mission, hasn't indicated which camera produced which picture, but it released a number of them, including a distant view of the collision, close-ups taken shortly after, and an animation showing the sudden brightening after the collision scattered material into space.

For those uncertain, the collision didn't produce enough light on its own to be visible in these images. Instead, the debris ejected from the asteroid by DART reflected a lot more sunlight than the asteroid could on its own.

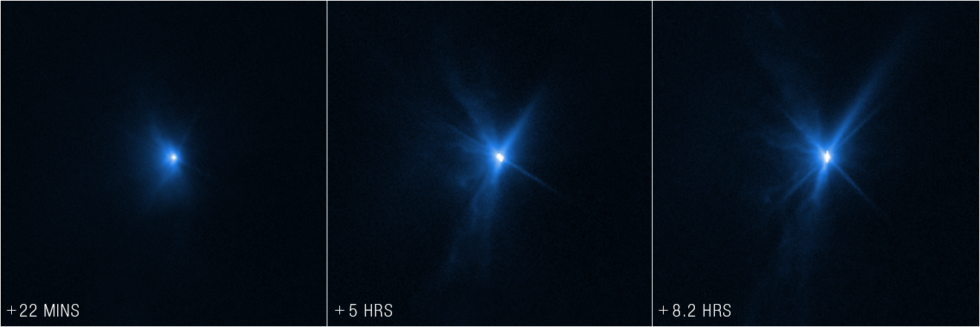

The brightening was large enough that Earth-bound telescopes also caught the brightening; in a few cases, their operators put the images online as they became available. Both of the ones I've found show the Didymos/Dimorphos system moving peacefully past background stars from Earth's perspective (with most of the light reflected off the far larger Didymos). Suddenly, the object brightens significantly, with the debris gradually moving off to one side of the asteroids.

There are two big differences between the images. One image taken by the ATLAS project, which is based in Hawaii but has telescopes there, South America, and South Africa—the collision was only visible from the last of those. In its image, the asteroid is moving right to left against the background stars.

In contrast, the Las Cumbres observatory's data from a telescope in South Africa shows the Didymos system moving across the star field in the opposite orientation. But it also has some rather significant information: time stamps for each exposure in the animation, which makes it clear that most of the action took place over roughly a half hour.

The ESA has also produced a video of the collision that covers the same time period, and posted it online.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.