We've now cataloged thousands of planets that orbit distant stars. For most of them, our knowledge is limited to basic statistics: their size, mass, and orbital distance from their host star. And, due to the difficult-to-comprehend distances within our galaxy, it's likely that this will remain the sum of our knowledge about them for generations.

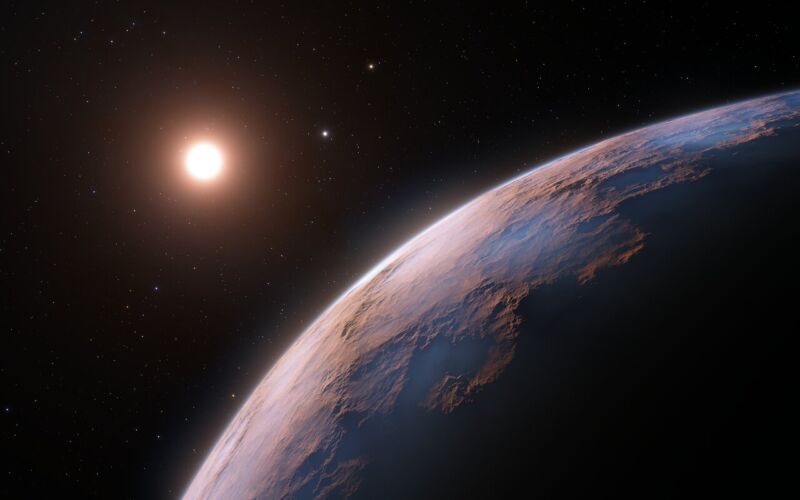

For the small number of planets closer to Earth, however, there's the chance to learn much more. Plans are already underway to study the atmospheres of planets within about 30 light years of Earth over the next few decades, and improvements in existing technologies have the potential to reveal even more. So the discovery of an Earth-sized planet orbiting Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun, was exciting news. We now have the potential to learn much more about this rare planet.

And now, scientists have confirmed that this planet isn't alone; at least one more planet orbits Proxima Centauri. And it turns out to be an unusually light one, with only about double the mass of Mars.

Previous hints

The original discovery of Proxima Centauri b, an Earth-sized planet within its star's habitable zone, was made using of what's known as the radial velocity method. This method relies on the fact that, if a planet's orbit is oriented in the right way, traversing the orbit can take the planet nearer or closer to Earth. And, because gravitational attraction is mutual, it will tug the star it orbits closer to or farther from Earth, as well.

The motion of the star can be read from the light we receive from it. As it moves toward Earth, its light will be shifted toward the bluer end of the spectrum; when it's pulled away from Earth, the light becomes a bit redder. If these shift show a regular pattern, that can be an indication of a planet's orbit, with the magnitude of the shift telling us the planet's relative mass compared to the mass of the star. Since many planets are in multi-planet systems, however, interpreting the changing red and blue shifts can be challenging.

In the case of Proxima Centauri, there was a clear signal of planet b, which takes about 11 days to complete an orbit. That short orbit means it's very close to the star. Since Proxima Centauri is a dim red dwarf star, however, its habitable zone is quite close as well, with Proxima Centauri b being solidly within it.

Beyond that, there's strong indication of a planet (Proxima Centauri c) much farther out, with an orbit of roughly five years. We haven't, however, been doing the right sort of observations of Proxima Centauri for long enough to have data on more than a single orbit. As a result, this is still considered a candidate.

Finally, follow-up observations have hinted at the possibility of a Proxima Centauri d, orbiting close to its host star. But the signal had never reached the point of statistical significance. Until now, that is.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.