Neanderthals used sleek bone projectiles to hunt big game.

Archaeologists recently unearthed a bone projectile point someone dropped on a cave floor between 70,000 and 80,000 years ago—which, based on its location, means that said someone must have been a Neanderthal.

The point (or in paleoarchaeologist Liubov V. Golovanova and colleagues’ super-technical archaeological terms, “a unique pointy bone artifact”) is the oldest bone tip from a hunting weapon ever found in Europe. It’s also evidence that Neanderthals figured out how to shape bone into smooth, aerodynamic projectiles on their own, without needing to copy those upstart Homo sapiens. Along with the bone tools, jewelry, and even rope that archaeologists have found at other Neanderthal sites, the projectile is one more clue pointing to the fact that Neanderthals were actually pretty sharp.

Getting to the point

Archaeologists found the bone point in Mezmaiskaya Cave, high in the Caucasus Mountains (Mezmaiskaya is also home to the remains of three Neanderthals who lived around 90,000 years ago; anthropologists sequenced samples of their DNA in earlier studies). Herbivore teeth from the same layer of sediment dated to around 70,000 years old, and the bone point’s position near the bottom of that layer probably makes it closer to 80,000 or 70,000 years old. That makes it the oldest bone projectile point ever found in Europe (so far).

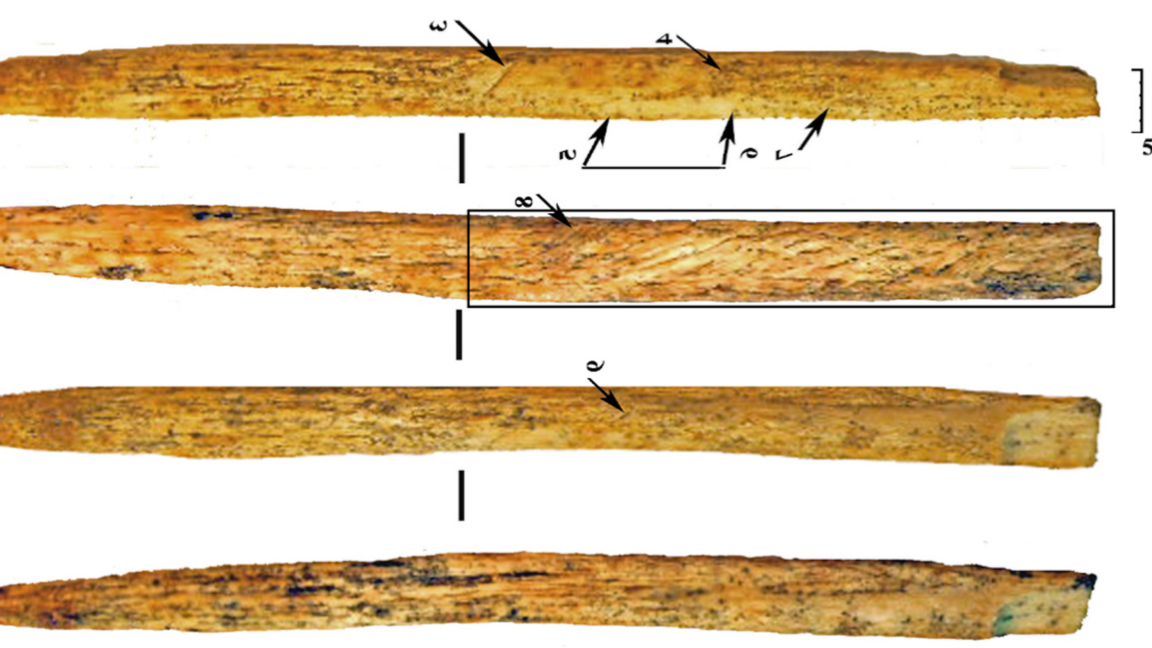

At about 9 centimeters long and just 6 millimeters wide at its base, the point is much too light to be of much use as a thrusting weapon, which means it must have been meant to strike from a distance. And it’s shaped for the purpose, sleek and straight.

The point lay near an ancient hearth, which the Neanderthals had built “in a natural hollow on top of a large limestone block.” A few stone tools, along with debris from flint-knapping, lay scattered nearby, hinting that the Neanderthals probably sat near the hearth to make and retouch their tools. Ten thousand years before them, other Neanderthals had lived and died here. And thousands of years later, still others would leave behind more traces of their lives and handiwork.

But the bone spear tip, as Golovanova and colleagues point out, is unique (and pointy).

Paleolithic weaponsmithing 101

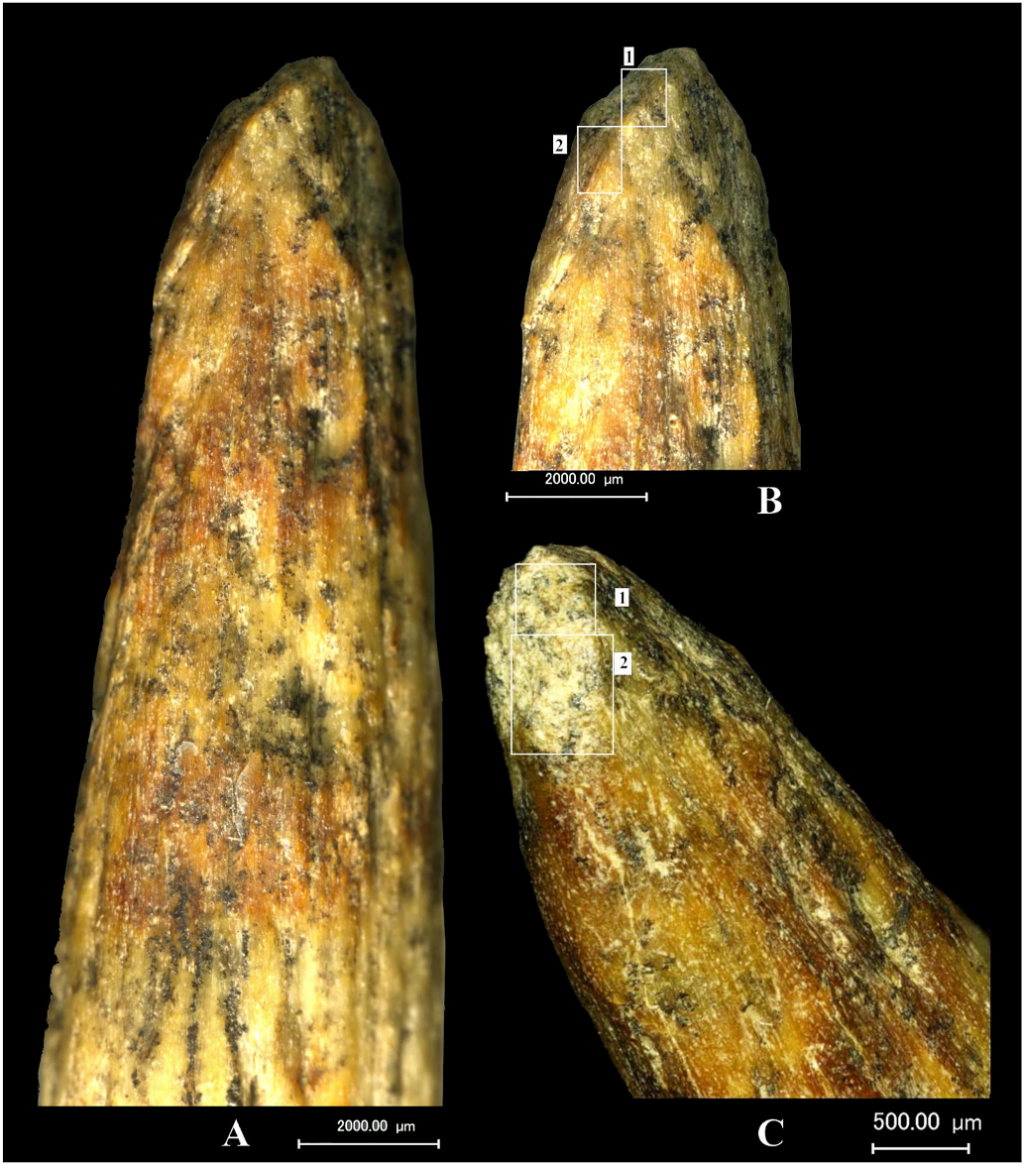

The point is shaped from the hard outer layer of bone (called cortical bone), probably from one of the massive leg bones of a bison. Under the microscope, Golovanova and colleagues could still see the grain pattern that marked where muscle once attached to the bone, even though the original knob of bone that formed the attachment had been ground flat and smooth by the Neanderthal who made the point.

Golovanova and colleagues’ microscopes also revealed shallow, parallel grooves where Neanderthal crafters had used stone tools and carefully scraped, ground, and polished the bone into exactly the right shape without breaking or splintering it. A couple of discolored spots also reveal that the point’s maker hardened its tip in a fire.

And if the tip doesn't seem as sharp as you'd expect, Golovanova and colleagues say it's sharp enough.

"To be an effective hunting weapon," write the archaeologists, "the bone point does not need to have a sharply pointed (needle-like) distal end (in contrast to bone awls), but it needs to have a strong, conical tip, symmetrical outlines, and a straight profile."

Traces of bitumen, or tar, on the point—which Golovanova and colleagues identified using spectroscopy—show that it must have been secured to its wooden haft with the sticky substance. That’s also how Neanderthals mounted many of their stone tools, so it’s not surprising that they’d do the same with a bone point. But making and using tar or resin requires a fair amount of technical know-how, and it’s easy to get it wrong and end up with an unusable mess.

Earlier hominins made bone tools, too; archaeologists have found a hippo femur hand ax made by Homo erectus and even some knapped bone dating back 1.5 million years. But those tools were roughly shaped, using the same chipping and flaking methods their makers would have used on stone. For some things, that works, but for something like the streamlined spear point from Mezmaiskaya, working bone takes different techniques: less flaking, more grinding.

Working bone into a streamlined, aerodynamic spear point, then hafting it onto a shaft with tar that had to be extracted and refined before use takes some sophisticated knowledge and skill. And it’s clear that the Neanderthals developed that skill on their own, instead of acquiring it from our species through some sort of prehistoric ITAR violation. Even so, Golovanova and colleagues note in their paper that “the production technology of bone-tipped hunting weapons used by Neanderthals was in the nascent level in comparison to those used and introduced by modern humans.” (Which seems a bit rude.)

Slightly damaged, use at own risk

A small crack at the tip of the spear point shows that some Neanderthal hunter used it at least once and managed to hit something. Golovanova and colleagues examined the crack and the finer network of cracks (visible in micro-CT images) that spread back and out from the original break. Those cracks closely resembled damage from a head-on impact, which archaeologists have seen in bone tools from other sites and in experimental studies (also called “archaeologists made some bone-tipped spears and threw them at things to see what would happen,” which is an excellent approach to science).

And apparently a bone spear point was worth trying to fix up and reuse, because traces of grinding show that someone tried to smooth out the crack, probably with a stone tool.

What kinds of prey were the Neanderthals of Mezmaiskaya Cave hunting? Based on the bones found in the cave, many of which show marks from cutting and scraping, the local menu included some birds and small mammals, but also bigger game like bison, deer, relatives of modern horses, and wild sheep and goats.

The point is, interspecies interactions are complicated

Archaeologists have found plenty of evidence that Neanderthals used bone tools for all sorts of things, from shaping and retouching stone to softening animal hides. The projectile point, though, is the first evidence that Neanderthals knew how to carefully work bone into a particular shape, instead of just picking up a conveniently shaped rib to smooth out some hides.

Using specific processes to sculpt bone, combined with using ocher to decorate things and using tar and resin to stick things together, is part of what anthropologists have defined as “modern” human behavior. And it looks like Homo sapiens and Neanderthals each worked most of it out on their own, separately, long before the two species met.

There’s good reason to think that the two groups eventually traded some key bits of technology here and there, but that exchange wasn’t the one-way street that anthropologists once expected.

Journal of Archaeological Science, 2023 DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106223; (About DOIs).

Hope you enjoyed this news post.

Thank you for appreciating my time and effort posting news every day for many years.

News posts... 2023: 5,800+ | 2024: 5,700+ | 2025 (till end of March): 1,357

RIP Matrix | Farewell my friend ![]()

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.