Visual change could be a powerful tool to communicate about how humans are changing the world

Following days of torrential rain, more than a dozen rivers in Vermont overflowed in early July, causing catastrophic flooding. Some parts of Vermont saw up to 23 centimeters of rain, or 9 inches, an amount exceeding even the rainfalls from Hurricane Irene in 2011. Once considered 1-in-100-year events, such floods are set to become more frequent as climate change warms the region, scientists say. That’s because warmer air can hold more moisture.

This time, my hometown of Burlington was largely spared. But Lake Champlain, which runs the length of the city, was not. As the water from the Winooski — a 145-kilometer river that swamped the state capital, Montpelier — flows into the lake near where I live, so too does the garbage, gasoline and other pollutants that it swallowed up.

I glimpsed this pollution firsthand while biking with friends on a path along the lake shortly after the worst of the flooding. The south end of the lake, where we started, remained surprisingly clean and free of debris, appearing light blue. But as we biked north, past the junction of river and lake, the water turned murky and brown.

That color shift reminded me of something I’d recently read about deep-sea divers in Estero Salado, a fishing town in the Dominican Republic. The divers describe similar changes to ocean hues where they fish, and their color vocabulary is intricate. They speak of blue, black, yellow, green, purple and chocolate to describe the seawater’s appearance at different times and under different circumstances, writes medical anthropologist Kyrstin Mallon Andrews in July in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. These colors tell the divers about the state of the water and possible impacts on the behavior and visibility of sea life, such as depth, turbulence and influx of runoff from storms.

Divers also speak of drastic changes to those colors over the years. Purple water, which “surpasses clean,” has become increasingly rare. Yellow water, caused by flooding in the nearby river and toxic runoff from the region’s rice fields, wreaks havoc on once fertile fishing grounds. Longer hurricane seasons turn the waters chocolate brown — a color too dangerous for diving — for months rather than weeks.

My own experience and that of the deep-sea divers made me wonder if using color to describe climate change could work as a communication tool. When I pose the idea to Tim Edensor, a social and cultural geographer at Manchester Metropolitan University in England, he concurs.

Historically, the colors of a person’s world would have stayed fairly constant, he says. But climate change is rapidly altering our visual environment. And those changes can be hard to ignore. “This transformation of the color of the water, I think this is really quite perturbing and it’s also disorienting,” he says.

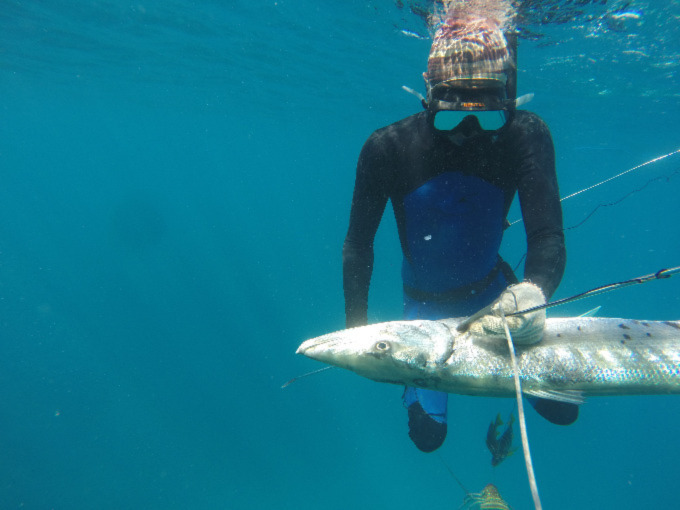

Deep-sea divers in the Dominican Republic say that clean water colors, such as blue (shown) and an even purer “purple,” are becoming increasingly rare as climate change alters the coastal ecosystem where they fish.

KYRSTIN MALLON ANDREWS

Such color changes are not limited to our waterways. Scientists have been talking about changes to the world’s color palette for several years. Here in New England, autumn’s vibrant leaves could become duller due, in part, to warmer nighttime temperatures that slow chlorophyll’s degradation process, researchers say. And satellite images show that while much of the Arctic is getting greener, some parts are turning brown, a sign that the vegetation could be dying (SN: 4/11/19).

Many flowers, meanwhile, have increased the amount of their ultraviolet pigments, a natural sunscreen to protect against rising temperatures and a thinning ozone layer, researchers reported in 2020 in Current Biology. While these changes are invisible to the human eye — we can’t see UV radiation — the flowers appear darker to pollinators. That change in hue could reduce a pollinator’s attraction to affected flowers, the researchers wrote.

When it comes to the world’s waterways, satellite images taken over the past 20 years show that over half the world’s oceans have become greener, researchers reported in July in Nature. Dissolved organic material in the water or changes to the type or quantity of phytoplankton are the most likely culprits, says Emmanuel Boss, an aquatic physicist at the University of Maine in Orono. “The bacteria are very happy. There is a whole microbial community that I think is having a blast.”

Another study of satellite images found that lakes in areas where average summer temperatures were once moderate and the waters froze come winter are also likely to switch from blue to green or even brown as the climate warms in coming years (SN: 10/3/22). Hot spots for this shift include northern Europe and northeastern North America.

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.