"Initially, Congress almost treated the program as a joke."

The next year is crucial for the future of NASA and its plans to extend human activity in low-Earth orbit. For the first time in decades, the US space agency faces the not-too-distant prospect of failing to have at least one crew member spinning around the planet.

Over the next several months, NASA will finalize a strategy for its operations in low-Earth orbit after 2030. Then, toward the end of next year, the space agency will award contracts to one or more private companies to develop small space stations for which NASA and other space agencies will become customers rather than operators.

But none of this is certain, and as NASA faces a transition from its long-established operations on the International Space Station to something new, there are many questions. Foremost among these is whether NASA really needs to continue having a presence on low-Earth orbit at all, especially as the space agency's focus turns toward the Moon with its Artemis Program.

Microgravity research remains essential

The answer to that question is definitively yes, said Pam Melroy, the deputy administrator of NASA, in an interview.

“It really is on us to tell our story as well as we can," she said. "I don’t think people realize the connection between low-Earth orbit to Artemis, and Moon to Mars, and future human exploration. I hope to help people understand better why it’s so important for us to push hard on this.”

In recent years, as NASA has been able to support a crew of four astronauts at a time on the space station, the space agency has started to maximize the scientific potential of the orbiting laboratory. This is not just for basic research in microgravity but for studying the long-term health impacts of humans in space.

"We are so not done with research in microgravity," Melroy said. "We’ve gotten ourselves to the point where we kind of understand the risks of a one-year duration mission in space, but we’re going to have to keep pressing on that because we really have to get our arms around mitigations and solutions for what will likely be a two- or three-year trip to Mars."

That goes for life support as well, known in NASA jargon as ECLSS. On the space station, NASA has pushed water recycling and other critical technologies toward 95 or 97 percent efficiency. But for long-duration missions to Mars and elsewhere, these technologies need to be 100 percent or very, very close to it.

In August, the space agency published a draft version of its "Microgravity Strategy" that will formally establish its low-Earth orbit research and technology development goals in the 2030s and beyond and determine which capabilities it needs to complete them. After collecting feedback from the space community, Melroy said a final version of this document should be completed by the end of this year.

NASA's needs in low-Earth orbit will set the stage for the pivotal second phase of the space agency's commercial space station program.

Can anyone actually build a commercial space station?

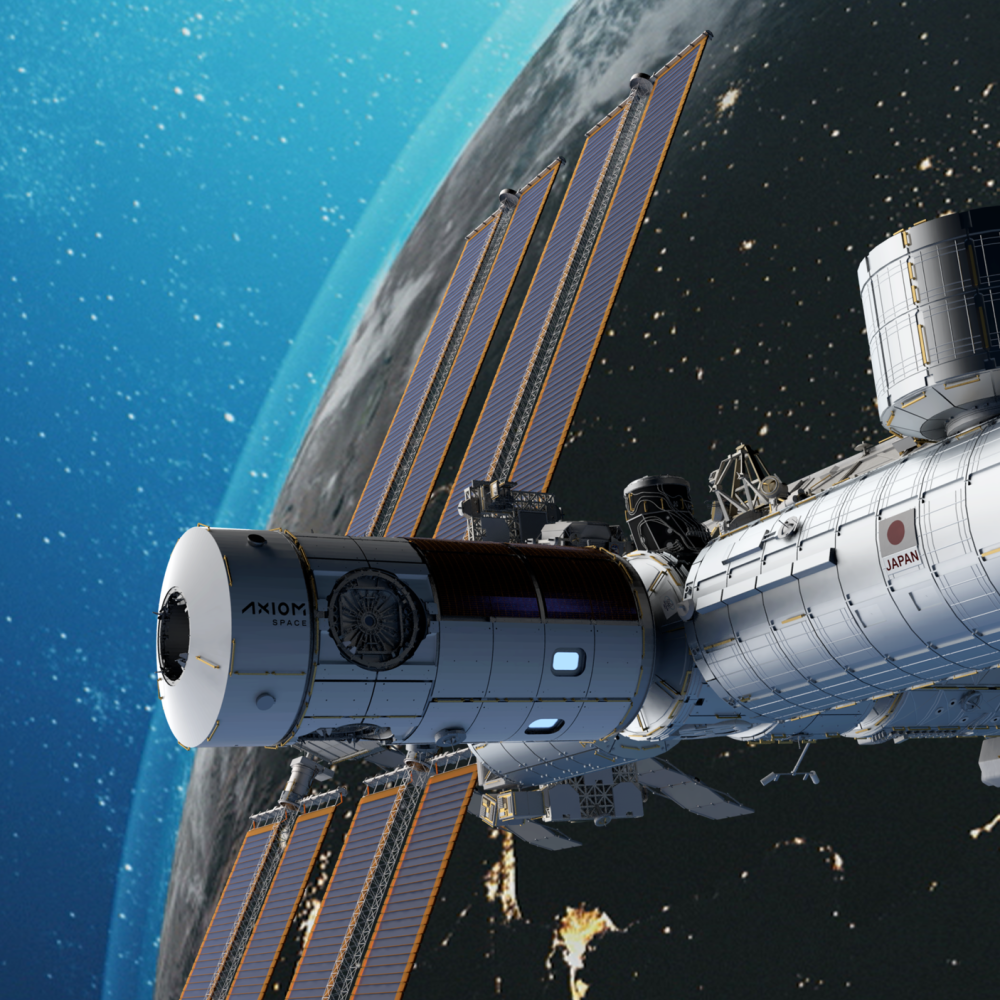

Three years ago, NASA awarded contracts to three companies—Blue Origin, Nanoracks, and Northrop Grumman—valued at between $125 million and $160 million—to begin preliminary work on commercial space stations. A fourth firm, Axiom Space, had received $140 million a year earlier. But the road has not been easy for these companies as they embarked on NASA's CLD program, which stands for "Commercial LEO Destinations."

Some of the CLD bidders have already hit roadblocks. Axiom Space is facing significant financial headwinds and has repeatedly delayed its timelines for module launches. Northrop Grumman dropped out, essentially saying its business case could not close. Northrop later joined a team led by Voyager Space, which had acquired Nanoracks.

Much will depend on how NASA structures the "request for proposals" for the second phase of the CLD program, which is expected to be issued next year. The commercial companies want to see how much funding is on offer—and specifically what the space agency's requirements are. There are also likely to be new entrants, including Vast Space and SpaceX, and potentially other vendors. NASA would like to award two contracts to create competition, but this is not certain.

One problem for NASA is that none of these companies are sure bets. Axiom had been considered a favorite, but its funding challenges are pretty grim. Although it has met its contractual milestones, Blue Origin does not seem overly committed to the program, and it may be waiting to see how much money is available in the next phase of CLDs. Voyager Space has some good international partnerships, but the company is unproven. Vast Space is intriguing, but it's not clear that the company's station concept will meet NASA's requirements. And SpaceX, with its Starship vehicle, is a wildcard. However, sources indicate the CLD program is not a priority for SpaceX, which already has so much else on its plate with Starship.

For NASA's part, Melroy acknowledged that the space agency is asking a lot of commercial providers. She said it's likely that NASA will ask for basic operations in 2030 before seeking a broader array of services from private space stations later on.

“One of the things we realize is that this might take longer to get to the ultimate destination," Melroy said. "Maybe we’ll get a minimum viable product by 2030, but all of our requirements or desires will probably take some time. We could take a phased approach."

Does NASA really care about this?

One way to assess NASA's prioritization of CLDs, and the support for the program in Congress, is to look at budgets requested by the White House and funding allocated by Congress. This is what the program has asked for and received since its inception in fiscal year 2019, according to data from The Planetary Society:

- FY 2019: $150 million requested, $40 million allocated

- FY 2020: $150 million requested, $15 million allocated

- FY 2021: $150 million requested, $18.1 million allocated

- FY 2022: $101 million requested, $102.1 million allocated

- FY 2023: $224 million requested, $224.3 million allocated

- FY 2024: $228.4 million requested, $228.4 million allocated

- FY 2025: $169.6 million requested

- FY 2026: $403.4 million requested

For the first three years, the program was virtually unfunded. "Initially, Congress almost treated the program as a joke," said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at The Planetary Society. However, in recent years, as it has sunk in that the International Space Station really is likely to reach its end of life in 2030, Congress has become more amenable to funding the program.

But it remains to be seen, Dreier said, whether NASA is truly committed. The space agency has repeatedly stated that it wants to maintain a presence in low-Earth orbit, but it has yet to fully make the case for why that is necessary. (This is one reason for the work on the Microgravity Strategy discussed above). Geopolitics plays a major role, of course. If the United States were to deorbit the International Space Station in 2030, it would be "grounded," whereas China would still be flying a fairly large orbiting space station. US space agency officials are understandably sensitive to being perceived to be falling behind China.

Nevertheless, Dreier said, NASA appears to be treating the CLD program as more of an experiment than fully committing to the strategy. Commercial space stations will likely require billions in funding and a commitment from NASA to be an anchor customer for years. NASA has not been acting that way in its budget requests so far.

“It’s an experiment that’s been worth running, with only $650 million spent over the last five years on this," he said. "That's a single-year budget overrun on some projects. So it’s interesting to try it. But is there really a national priority to maintain a presence in low-Earth orbit? Because if it is, we’re not treating it that way."

Is a gap really that bad?

When you talk to knowledgeable people at NASA and within the commercial space industry, there is a general sense that we will be lucky to have a single commercial space station option by the end of 2030, when an uncrewed SpaceX Dragon vehicle is due to pilot the International Space Station into the Pacific Ocean.

Some people have suggested that NASA keep flying the space station longer, but there are issues with this. First, there is a problematic partnership with Russia, which is increasingly difficult to maintain as the war in Ukraine drags on. Additionally, by then, parts of the station will be more than 30 years old, and cracking problems may only worsen. There is also the budget. Flying, operating, and supporting the station costs NASA about $3 billion a year, and it likely could cut that by two-thirds with a private station alternative.

But perhaps most importantly, stalling on ending the International Space Station's life only further weakens the business case for private space station operators. Particularly for companies like Axiom and Voyager, uncertainty in the end of life for the station makes fundraising that much more difficult. Investors want to know that NASA really will need their private stations.

For all of these reasons, NASA will likely end the space station's life about six years from now. Is it the end of days if NASA goes without a low-Earth orbit space station for several months or even years? One key commercial space official at the space agency, Phil McAlister, suggested that maybe it wouldn't be.

"That would be bad, and I don't want a gap," McAlister said in November 2023. "But if the CLDs are not ready, we might have one. Personally, I don't think that would be the end of the world. It would not be unrecoverable, especially if it's relatively short-term. It might impact some research somewhat, but we could leverage Crew Dragon and Starliner to lessen the impact of a gap."

McAlister led the CLD program until this past summer, at which time he was moved within the agency to a senior advisory position. Needless to say, the acceptability of a gap is not NASA's official position.

If you build it, will they come?

There are other uncertainties hanging over the CLD program and its long-term viability. One is whether there really is any market demand beyond government astronauts. An influential report completed in 2017 found that the answer to that is "maybe not." The problem then, as now, is that there is no killer app that makes it profitable for humans to live and work in space.

"Venture capitalists whom we interviewed noted that the projections of revenues and costs are so uncertain that they would have no interest in financing a space station until projected revenues from these activities show signs of materializing," the report stated, highlighting this concern.

Eventually, NASA would like to transition from being an anchor customer to becoming one of many customers. But who would these other customers be? Certainly governments of some nations will want to send individuals to these stations for prestige purposes. There will probably be at least a trickle of space tourists. But no one is sure of the overall demand, where it will come from, and how much people will be willing to pay.

There is also a concern that automated manufacturing in low-Earth orbit might cannibalize some of the potential human activity in space. For example, Varda has already demonstrated the ability to do pharmaceutical research in orbit, with its first mission landing earlier this year after spending eight months in space. Varda and others are working to develop automated spacecraft that could do manufacturing and research work in microgravity for far less money than a worker on a private space station.

Then there is SpaceX, with Starship. Although the company may not be ready to bid for NASA's formal CLD program, if Starship begins flying regularly, it is not too difficult to see the potential for short-duration orbital flights for dozens of customers in the 2030s. This may offer a more appealing, lower-cost option for space tourists who might otherwise be interested in time on one of the private space stations.

Ultimately, if NASA decides it needs private space stations to succeed, it must commit to supporting the private companies. Space stations are big, difficult, and expensive problems. NASA isn't seeking another International Space Station, which took more than a decade and $100 billion to construct, but it needs safe and functional habitats. That won't come cheap, and the clock is ticking.

RIP Matrix | Farewell my friend ![]()

Hope you enjoyed this news post.

Thank you for appreciating my time and effort posting news every day for many years.

2023: Over 5,800 news posts | 2024 (till end of September): 4,292 news posts

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.