For more than three years, NASA has been intensely focused on the Artemis Moon program. This high-profile international effort, spearheaded by the US space agency at a cost of nearly $7.5 billion per year, seeks to return humans to the lunar surface in the mid-2020s and establish a sustainable presence in deep space.

But in recent years, NASA has been funding a second, much smaller-scale Moon program, at just 3 percent of the cost of Artemis. This is the "Commercial Lunar Payload Services" program, which seeks to use private companies to send small- and medium-size landers to the Moon's surface for primarily science-based missions. Its budget is about $250 million per year.

This program, known as CLPS, is showing some promising signs and will beat the Artemis program to the Moon by at least a couple of years. Moreover, it represents a bold new effort by NASA's Science division, which is seeking to leverage the emerging commercial space sector to radically increase scientific and exploration capabilities. If successful, the CLPS model of exploration could be extended to Mars and beyond.

But will it be successful? We're about to find out.

Origin of CLPS

Like the Artemis program, the origin of CLPS can be traced to the middle of the Trump administration, when White House officials sought to refocus NASA's exploration programs on the Moon in 2018 after a long period of heavy focus on Mars. This shift resonated with the associate administrator in charge of NASA's science programs, Thomas Zurbuchen, who came into office in late 2016.

Since the end of the Apollo program in the 1970s, NASA had sent a handful of orbiters to the Moon but had not made a soft landing there in more than four decades. In the meantime, the space agency had landed half a dozen times on Mars and explored the rest of the Solar System.

"I had felt for quite a while that we had not focused enough on the Moon," Zurbuchen said in an interview with Ars. "It seemed odd that every celestial body in the Solar System was interesting except the one that is in the sky every night.”

Other scientists were starting to become very engaged in lunar research, too, especially with NASA's interest in the potential to harvest water ice at the poles of the Moon. The commercial space industry, spurred in part by the Google Lunar XPrize, had also started working on innovative lander concepts. And there was one other data point; NASA's successful program to have commercial companies deliver food and supplies to the International Space Station had started to work well.

Zurbuchen wondered whether this public-private model might be extended to science missions. In other words, were commercial companies up to the task of building small landers, hiring private launch companies, and delivering experiments for NASA and other customers to the lunar surface?

Working with key allies inside NASA, including David Schurr of the Planetary Science Division and Steven Clarke, a deputy associate administrator, Zurbuchen established the CLPS program. After selecting a pool of a dozen US companies eligible to bid, NASA started to competitively award contracts valued at between $80 million and $100 million in May 2019 for lunar delivery missions. These costs were far less than NASA would have paid as part of a traditional procurement process.

Not all of these landers will be successful, at least initially. It represents a huge technological leap for a private company to build a spacecraft and lander and operate the craft at nearly 400,000 km from Earth. Zurbuchen used the phrase "shots on goal" to characterize this risk, consistently telling policymakers there was a 50-50 chance of success for early CLPS missions.

"You have to buy in on the risk," Zurbuchen said. "If the chance of success needs to be 80 percent, I need to put a safety and mission assurance program onto it. And I don’t want to do that because then I’m squeezing some of the entrepreneurial energy. I just really believe that the entrepreneurial ecosystem is one of the core strengths of the United States. We’re second to none. And if we’re not using that as part of our leadership paradigm, we’re missing out.”

The VIPER pushback

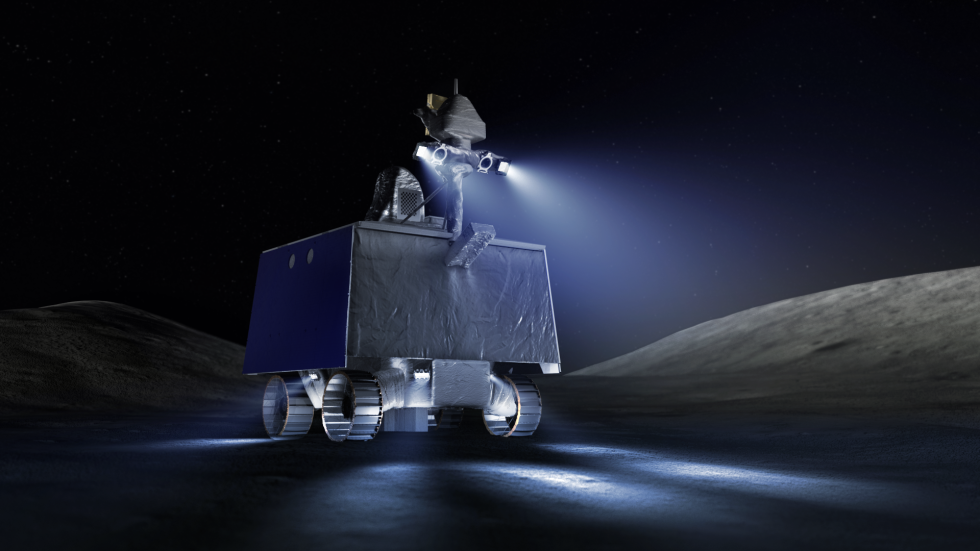

It's one thing to take a chance with relatively modest scientific experiments; it's another thing to put major NASA missions on CLPS. But that's what Zurbuchen decided to do in June 2020 by awarding the VIPER mission to a CLPS provider, Astrobotic. The company received a $199.5 million contract to deliver VIPER—the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover—to the south pole as early as late 2023. It is scheduled to fly there on the company's still-in-development Griffin lander.

This is an important scientific mission tasked with searching for ice at the south pole and using a one-meter drill to prospect for subsurface samples. The total value of the mission is $660 million, and it matters to scientists and NASA's human exploration division, which hopes to send astronauts to the south pole in the 2020s.

Because there was so much riding on VIPER, Zurbuchen has received pressure from within and outside of NASA, from scientists and politicians alike, to move to a more "traditional" delivery for VIPER. For a typical NASA science mission, this would mean that NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory would design the lander and then contract out its construction to a traditional contractor, most commonly Lockheed Martin.

In response to concerns about VIPER, Zurbuchen asked for an independent assessment of the top risks for the delivery of VIPER to the Moon. Astrobotic willingly cooperated in this process, he said, because they welcomed the technical assistance with their program.

Zurbuchen then asked his team to consider other options for putting the rover safely in Nobile Crater at the south pole of the Moon. When the costs and timelines came in, he realized that bypassing CLPS for VIPER would effectively kill the entire commercial lunar program by eating up its funding—not just for VIPER but for the next several deliveries after that. "It was clear to me that if we went with a traditional delivery, we would be abandoning all of CLPS," Zurbuchen said.

He was not willing to accept this. And after receiving buy-in from NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy and Associate Administrator Bob Cabana, Zurbuchen made the decision to keep VIPER on Astrobotic's Griffin lander. As part of this move, Astrobotic agreed to subject Griffin's propulsion system to more rigorous testing. Additionally, NASA decided to build a second set of instruments as a backup plan.

"With the other CLPS missions, I’m perfectly fine with a 50-50 chance," Zurbuchen said. "But with VIPER, the cost is higher, and as a taxpayer, I would like the government to put more effort in to increase its chance of success."

Betting on commercial

Zurbuchen is betting on these private companies because he understands that Astrobotic and other CLPS contractors, such as Intuitive Machines and Masten Space, must be successful in landing on the Moon or their businesses will dry up.

To date, NASA has awarded seven CLPS missions and will likely award two or three more later this year. For now, Zurbuchen has support from the White House and Congress for this approach. But will support last if the first couple of landing attempts create new craters on the Moon?

We should know soon. Both Astrobotic (with its smaller Peregrine lander) and Intuitive Machines (with its Nova-C spacecraft) are scheduled to make their first attempts later this year, although those schedules may slip. Both companies have faced technical problems and had supply chain issues that have slowed them down. But each is getting close. In fact, later today, Astrobotic will publicly reveal its lander for the first time.

Zurbuchen and other supporters of CLPS at NASA are adamant in their support because they think it's healthy for the space agency to accept some risk in return for much faster and less expensive development programs. Traditionally, NASA has not been able to afford to fail because of political pressure. So the agency has primarily used "linear" design for new programs, during which years are spent designing and testing small pieces of a project. Only after considerable analysis are the components put together and tested. This is the safest way to build a vehicle and gives the greatest chance of succeeding the first time out. But it is also a costly and drawn-out process.

Commercial companies, such as SpaceX and Rocket Lab in the launch industry, have adopted an iterative design methodology, in which the goal is to fly faster and learn from mistakes and failures in flight. In this sense, each subsequent vehicle improves upon the earlier design and has a higher chance of success.

Should CLPS be successful, it will almost certainly mean that NASA will get more bang for its buck, with lower-cost science done more quickly. While there may be some painful learning experiences, once this industry matures, it could apply to not just the Moon but other destinations in the Solar System. The planetary scientists who authored the "decadal survey" of Solar System research priorities, published Tuesday, recognized this.

"NASA should continue to support commercial innovation in lunar exploration," the report recommended. "Following demonstrated success in reaching the lunar surface, NASA should develop a plan to maximize science return from CLPS by, for example, allowing investigators to propose instrument suites coupled to specific landing sites. NASA should evaluate the future prospects for commercial delivery systems within other mission programs and consider extending approaches and lessons learned from CLPS to other destinations, e.g., Mars and asteroids."

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.