Sometime between 200 and 500 CE, someone crossing a high mountain pass in Norway discarded a shoe. More than 1,500 years later, an unusually warm summer melted centuries of accumulated snow and ice, revealing the ancient shoe—and an assortment of other objects left behind by ancient and medieval travelers on the snowy mountain trails. Archaeologists with the Secrets of the Ice project recovered the shoe in 2019, finished conserving it in 2021, and recently published a report about the site and the finds.

The report “is for internal archiving only and [is] not published,” Secrets of the Ice co-director Lars Holger Pilø told Ars in an email. “In addition, it is in Norwegian.”

But Pilø and his colleagues recently shared some highlights via the project’s social media and in a conversation with Ars.

High-altitude high fashion

The shoe isn’t what you’d expect to find in a high mountain pass. It looks more like a sandal than a hiking boot, with its decorative cutouts and an open, lace-up top that barely reaches the ankle. Far to the south and east, in the Roman Empire, it would have been fashionable footwear; conservator Vegard Vike at the Museum of Culture and History in Oslo, Norway, matched it to a type popular in Roman cities during the 400s and 500s CE (also known as the Iron Age in most of Europe).

“The similarity to footwear within the Roman Empire is striking,” Pilø told Ars in an email. “It tells us that the people living in these geographically remote mountains had a connection to the continent. Roman imports have been found in South Norway previously (especially weapons), but the shoe tells us that ideas and fashion traveled as well.”

This particular piece of Roman fashion traveled to a mountain pass called Horse Ice Patch, 2,000 meters above sea level in the mountains of Western Norway—far beyond the boundaries of the Roman Empire even at its peak, but apparently not beyond Rome’s influence. Pilø and his colleagues used the shoe and centuries’ worth of other lost or abandoned items to trace the trails that traders and farmers once trekked through the cold, inhospitable landscape to reach markets or seasonal grazing pastures.

Today, if you just look around Horse Ice Patch, it’s almost impossible to spot the ancient and medieval trails that once converged there. But a closer look reveals objects that still mark the routes people walked long ago.

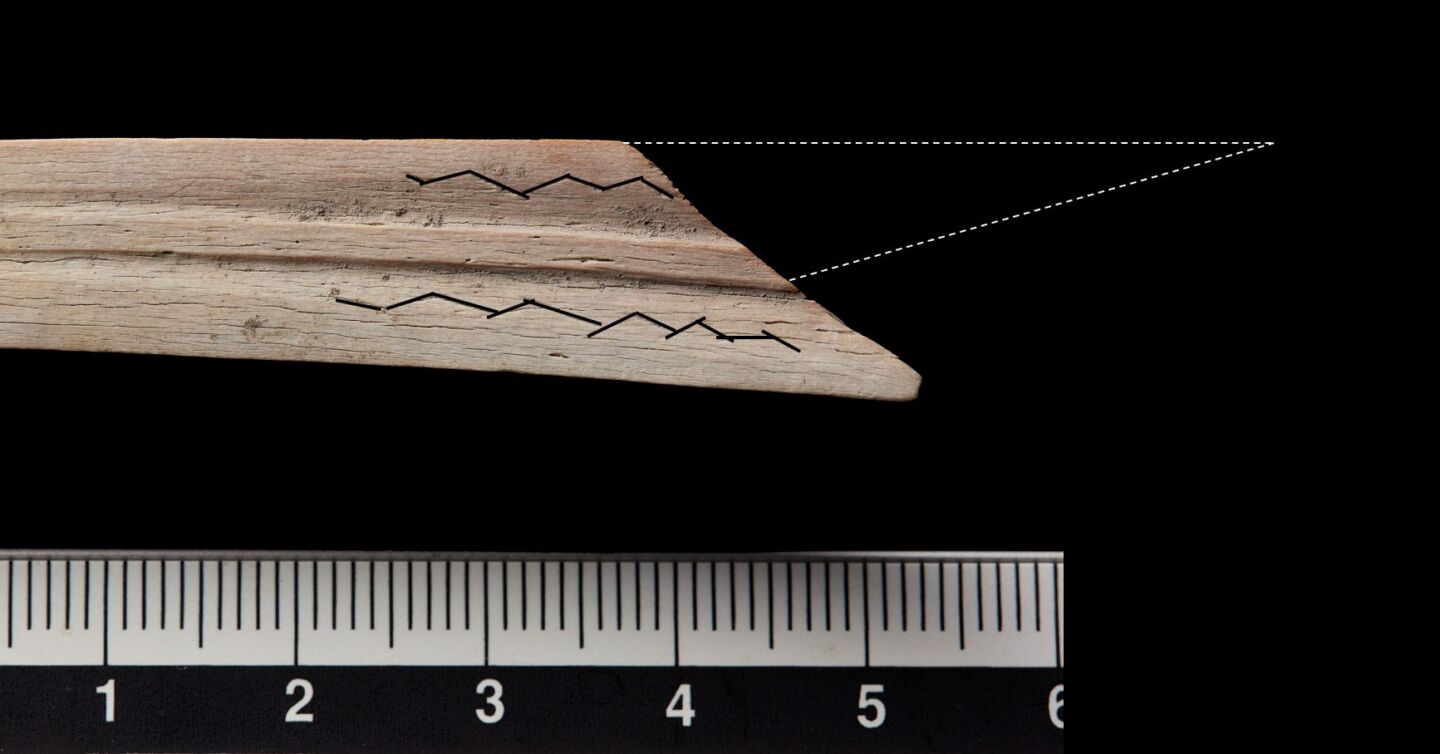

Near the Iron Age shoe and along the trails in and out of the pass, Pilø and his colleagues found a 2,000-year-old arrowhead made of reindeer antler and etched with a pair of zigzag lines. They’ve also recovered horse manure dating back to the Viking Age (about 800 to 1100 CE), as well as a horseshoe and a horse leg bone from the late Middle Ages. It’s clear that people used the pass for centuries.

“The high mountain passes went out of use mainly because better roads were built in the lowlands from the mid-19th century,” Pilø told Ars.

Before that, trails like the ones that converge at Horse Ice Patch were the only way a farmer in a valley like Skjåk could reach a port town on the Sognefjord, Norway’s longest and deepest fjord. The narrow, uneven trails had to be traversed on foot, leading pack horses; the terrain was too rough and steep for riding, let alone the comforts of sledges or carts.

Clues on ice

Pilø and his colleagues at Secrets of the Ice have spent the last 15 years mapping the network of routes across and through the mountains. They’ve had some help from hundreds of stone cairns that people in the past built as trail markers, but many of those ancient and medieval cairns are now gone, or the trails themselves are so long-neglected (and so rough to begin with) that it can be hard to see where the trail goes, even when you’re standing next to a cairn.

And, Pilø told Ars, “The cairns are difficult to place in time, as they do not contain material that can be dated by radiocarbon. So we date them by their association with the route. It is also likely that the large, well-built cairns (or 'trail markers' is perhaps a better word) are the most recent.”

For the most part, Pilø and his colleagues have traced and dated the trails by finding the objects ancient travelers dropped or threw away. At other sites in the mountains, those objects have included a surprising number of shoes, some dating back 3,000 years to the Bronze Age.

According to Pilø, most of the shoes, including the Roman-era one from Horse Ice Patch, wore out during the trip, and people simply tossed them to the side of the trail and carried on with a fresh pair. In other words, even in a seemingly remote mountain pass that just skirts the edge of a glacier, people have been littering for centuries. But at least here, the old saying holds true: one person’s trash is another person’s archaeological evidence.

“You have this vast wilderness with no traces of humans, but then you realize it’s actually brimming with clues,” Secrets of the Ice co-director Espen Finstad told ScienceNorway. “It gives the landscape an entirely new story, another context than just an item you found in the ice.”

Archaeologists have found hundreds of cairns like this one in Norway's mountains, marking ancient routes to and from the passes.

This is Horse Ice Patch; the branch and leaves in the foreground are from grazing pastures in the valley below, probably carried through the pass as fodder for horses or other livestock.

A hiker found the remains of the ancient shoe melting out of the ice in 2019 after an unusually warm summer and alerted archaeologists.

The remains of the shoe, mid-conservation.

Conservation efforts for the shoe included careful reshaping and freeze-drying.

Conservator Vegard Vike made a replica of the shoe. This is what it looks like when it's unlaced and not wrapped around a foot.

The original shoe would probably have had animal hair on the outside, which would have helped it grip the snow better.

This shelter once offered travelers in the pass a break from the wind and snow.

This arrowhead, made of reindeer antler and probably also used to hunt reindeer, radiocarbon-dates to 2,000-3,000 years ago. One barb has broken off.

From farm to fjord

From farming settlements in the inland valley of Skjåk, a trail winds its way south and up toward Horse Ice Patch, eventually climbing from the valley floor to a windswept pass 2,000 meters above sea level. The trail forks at the pass; one route leads west through the mountains before descending to Sognefjord on the coast. Along this western route, Pilø and his colleagues found the stone foundation of a shelter that would once have been topped with wooden beams covered in hides to block the wind and snow.

“At the fjord, the travelers from Innlandet would have been able to acquire salt, barley, and dried fish in exchange for outfield products such as reindeer antler and pelts and probably also farm produce such as butter,” explained Pilø.

Meanwhile, the second route out of Horse Ice Patch leads east to the site of a 16th-century summer farm called Neto. Along this route, all of the artifacts found so far date to the late Middle Ages or early Renaissance—no earlier. That tells archaeologists that people probably weren’t using the eastern route before the start of Neto Summer Farm. (At the time, most farmers kept a permanent, "main" farm in a place like Skjåk, along with at least one "summer farm" at a higher altitude.)

“The basic idea was to move the farm animals to pastures in the mountains during summer so that the grass on the meadows of the main farm could be harvested and stored for winter fodder," Pilø told Ars. "It appears that leaf fodder was cut at the summer farms as well—we have found such leaf fodder melting out of the ice both at the Lendbreen Ice Patch and the Horse Ice Patch pass.”

Cold feet? No worries

The Iron Age shoe is a remarkable find, but 2,000 meters above sea level in the cold, rugged landscape of Norway’s mountains, it looks completely out of place.

However, Pilø says we should give ancient people more credit.

“In its current state, with just the rawhide preserved and the hair gone, it certainly looks like something we would not have used during glacier crossings today,” he told Ars. But the rawhide (untanned leather, which is usually stiff and strong) material of the shoe would originally have been covered with animal hair.

Pilø and his colleagues have found much older shoes, dating back 3,300 years, at other sites. These shoes were made with the hair on the outside of the shoe, probably with traction on the snow and ice in mind. To help keep feet warm and dry, the shoe's former owner probably stuffed the shoe with grass or fabric or wore the shoe over fabric foot wrappings. A 5,300-year-old hunter now known as Ötzi, whose mummified remains were recovered from a glacier in the Italian Alps, wore grass stuffing inside his shoes. And Pilø and his colleagues found several scraps of woven fabric not far from their discarded shoe in Norway.

“Obviously, they cannot compare to modern hiking boots, but they were considered functional enough and used for thousands of years,” Pilø told Ars. And in case you’re wondering, it’s a European men’s size 43, according to Vike, who made a leather replica of the shoe and tried it on. “With wool wrappings/socks, it would probably fit a size 42,” Vike said in a tweet.

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.