Gigantic extinct sharks have something to tell us from millions of years ago, and paleontologists are only just beginning to unravel that message. In a series of firsts, paleontologists have identified a growing number of paleo-nurseries, ancient sanctuaries where young sharks may have been born and where they grew until they were big enough to survive on their own in the larger sea. It’s a strategy some sharks continue to employ today, meaning it has been a successful evolutionary tactic for at least 23 million years.

The most abundant remnants we have of these apex predators are the teeth they shed over their lifetime. Cartilage, the major component of internal shark structure, doesn’t tend to survive fossilization. Given the considerable dearth of fossils, how can paleontologists ascertain the types and ages of extinct sharks? And how are paleontologists able to determine the site of a paleo-nursery from tens of millions of years ago in areas that are no longer underwater?

Answers with teeth

The answers lie with fossil teeth, from which paleontologists can determine species and estimate sizes—and, remarkably, the temperature and salinity of the water where the sharks lived. Although scientists aren’t yet able to establish the precise age of a shark from a fossil tooth, they can narrow it down to whether the shark was a neonate, juvenile, or adult, according to Matthew Gibson, the natural history curator at The Charleston Museum.

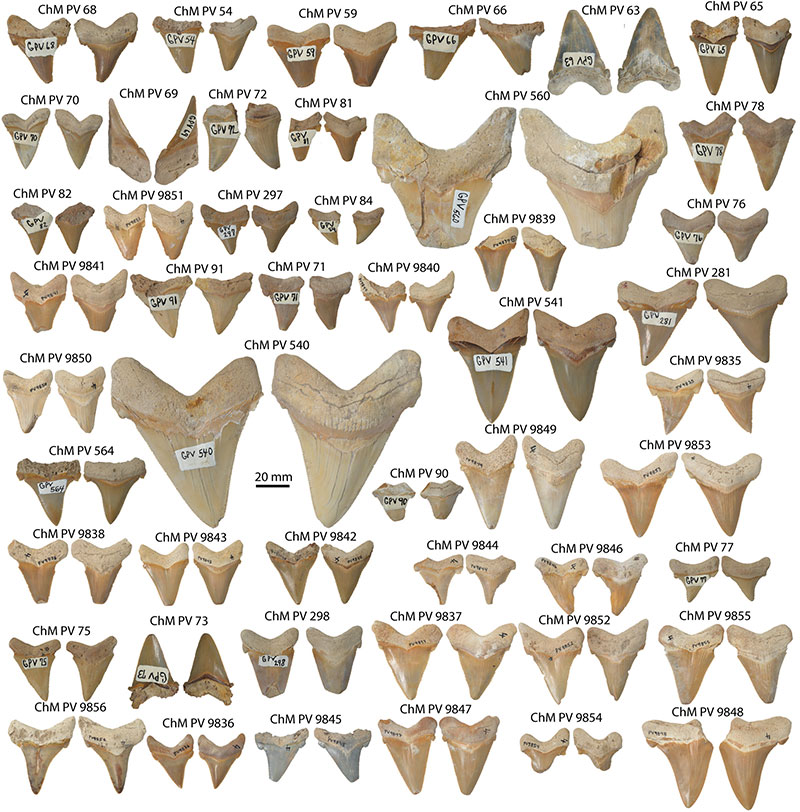

That’s critical because the most important clue to determining whether an area was once a paleo-nursery is a preponderance of teeth from young sharks. And it takes a lot of individual measurements and analysis on every single tooth from a site to determine what species, what age group, and what size of shark each tooth represents.

Despite the effort required, the work is being done. The first known megalodon paleo-nursery was found in Panama and described in a paper published in 2010. Megalodon (Otodus megalodon) tends to be the only terrifying, toothy leviathan in our collective imagination when it comes to extinct sharks. But there were a number of enormous ancient shark species over the past million years, all of which are known as megatoothed sharks. Since that discovery 12 years ago, more paleo-nurseries from other megatoothed sharks have been found throughout the world in countries like Peru, Chile, Spain, and the East Coast of the US. In 2020, the first paleo-nursery for ancient great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) was discovered in Chile. And in 2021, the first paleo-nursery for another megatoothed species, Carcharocles angustidens, was confirmed in South Carolina.

The three teams who discovered these new paleo-nurseries looked at significant numbers of fossil teeth: 28 megalodon teeth from Panama, 136 Carcharocles angustidens teeth from two sites in South Carolina, and a staggering 234 ancient great white shark teeth from three separate sites in Chile and Peru, 69 of which were from the paleo-nursery in Chile.

Dr. Jaime Villafaña is a paleontologist at the Center for Advanced Studies in Arid Zones (CEAZA) in Coquimbo, Chile, and the lead author of the ancient great white shark paper. He admitted that studying 234 teeth “was an incredible amount of work. The measurements were taken by Alonso Alvarado and supervised by me... This process and the associated tasks (database and images preparation) were performed in four months.”

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.