The award ceremony features miniature operas, scientific demos, and the 24/7 lectures.

Curious about why geologists lick rocks or how many nose hairs there are on a human cadaver? Perhaps you'd like a snazzy dead wolf spider to use as a biodegradable robotic gripper? How about a "smart toilet" that analyzes your urine stream and fecal deposits while taking a picture of your anus for good measure? These and other unusual research endeavors were honored tonight in a virtual ceremony to announce the 2022 recipients of the annual Ig Nobel Prizes. Yes, it's that time of year again, when the serious and the silly converge—for science.

Established in 1991, the Ig Nobels are a good-natured parody of the Nobel Prizes; they honor "achievements that first make people laugh and then make them think." The unapologetically campy awards ceremony features miniature operas, scientific demos, and the 24/7 lectures whereby experts must explain their work twice: once in 24 seconds and the second in just seven words. Acceptance speeches are limited to 60 seconds. And as the motto implies, the research being honored might seem ridiculous at first glance, but that doesn't mean it's devoid of scientific merit.

Viewers can tune in for the usual 24/7 lectures, as well as the premiere of a "non-opera" featuring various songs about water, in keeping with the evening's theme. In the weeks following the ceremony, the winners will also give free public talks, which will be posted on the Improbable Research website.

Without further ado, here are the winners of the 2023 Ig Nobel prizes.

Chemistry/Geology Prize

Citation: "Jan Zalasiewicz, for explaining why many scientists like to lick rocks."

Anyone who knows a geologist or paleontologist has likely learned of a peculiar habit: licking rocks. Those scientists will tell youthat it's a pretty good way to test if a rock is a rock or a piece of fossilized bone since the latter will stick to the tongue, and grinding said rock between the teeth for a moment can help ascertain the size of the grains—and thus whether the rock contains clay or silt. Zalasiewicz is a paleontologist at the University of Leicester in the UK, and he addressed the colourful history of the rock-licking practice, among other peculiarities, in an entertaining 2017 essay published in The Paleontological Association Newsletter.

"Wetting the surface allows fossil and mineral textures to stand out sharply rather than being lost in the blur of intersecting micro-reflections and micro-refractions that come out of a dry surface," Zalasiewicz wrote, recalling the time he licked a roadside rock that turned out to be a well-preserved Nummulites foraminifera. According to Zalasiewicz, this "taste for stratigraphy" might date back to an 18th-century mining engineer, surveyor, and self-professed mineralogist named Giovanni Arduino, who came up with categories for strata that eventually morphed into today's Geological Time Scale.

Arduino wrote a letter to Antonio Vallisneri, a professor at the University of Padua, in which he describes all the local rocks, minerals, and fossils in the valley of the Agno, including helpful tasting notes. For example, burnt fossil shells and bits of coal are "equally bitter and urinous." Water from springs flowing out of a stratum rich in marcasite and coal "have an acid spicy flavor" that Arduino likened to "the acidity of wine." One likes to think that Arduino would be pleased to learn that his "taxonomy of taste" remains a common analytical tool among modern-day rock lovers.

Literature Prize

Citation: "Chris Moulin, Nicole Bell, Merita Turunen, Arina Baharin, and Akira O’Connor, for studying the sensations people feel when they repeat a single word many, many, many, many, many, many, many times."

Most of us are familiar with the phenomenon of déjà vu: the sense that we've experienced something before, even though we haven't—an illusion of memory, if you will. The opposite of that is jamais vu, a fleeting sensation of novelty or unfamiliarity concerning something we have seen or experienced before: usually a word, but sometimes also people or places. Jamais vu is often a symptom of epilepsy or migraine. Moulin et al. had a hunch that jamais vu could be produced with so-called word alienation tasks and set out to test that hypothesis, conducting experiments with student volunteers from the University of Leeds.

The study participants dutifully copied the same selection of words over and over (and over) and were told to stop if they started feeling "peculiar," which usually occurred (in two-thirds of the participants) after 30 repetitions, or about one minute—the point of "semantic satiation." For instance, there were sensations of words losing their meaning the more one looked at them ("They just seem like a string of letters instead of a whole word"), or a familiar word suddenly seemed strange ("It doesn't seem right, almost looks like it's not really a word but someone's tricked me into thinking it is"). Those who reported experiencing déjà vu in their daily lives were much more likely to report experiencing jamais vu, suggesting a correlation between the two.

Mechanical Engineering Prize

Citation: "Te Faye Yap, Zhen Liu, Anoop Rajappan, Trevor Shimokusu, and Daniel Preston, for re-animating dead spiders to use as mechanical gripping tools."

Reanimator, arachnid version: Rice University researchers found a way to

use dead spiders for robotic grippers.

Preston Innovation Laboratory

Rice University graduate student Faye Yap noticed a dead curled-up spider in the lab hallway one day and learned that spiders curl up when they die because of internal hydraulics. She thought it might be cool to use the bodies of dead spiders as tiny air-powered grippers for picking up and maneuvering tiny electronic parts. So Yap and her colleagues—including adviser Daniel Preston—did just that. They transformed a dead wolf spider into a gripping tool with just a single assembly step, essentially launching a novel research area they have cheekily dubbed "necrobotics."

As we reported last year, a spider's prosoma, or hydraulic chamber, contains internal valves that enable the creature to control each leg individually. Once the spider dies, that control is gone, and the legs work in unison. All they needed to do was insert a needle into the prosoma of a dead spider and affix it to the spider's body with superglue to form a hermetic seal. The whole process took 10 minutes. The other end of the needle is attached to either one of the lab's test rigs or a handheld syringe. Administering tiny puffs of air pressurizes the chamber and activates the legs instantaneously, causing them to open. Depressurizing the chamber causes the legs to close up again.

The team tested their spider-gripper on a variety of objects. For example, they used it to remove a jumper wire on an electric breadboard to disconnect the LED, to pick up a block of red-dyed polyurethane foam, and even to pick up another dead spider. The spider-gripper could reliably lift objects that were more than 1.3 times the spider's body weight, exerting a peak gripping force of 0.35 millinewton. The spider-gripper also proved to be surprisingly robust, completing 1,000 open/close cycles before the wear and tear on the joints caused the body to break down after a couple of days. As a bonus, the spider bodies are fully biodegradable.

Medicine Prize

Citation: "Christine Pham, Bobak Hedayati, Kiana Hashemi, Ella Csuka, Tiana Mamaghani, Margit Juhasz, Jamie Wikenheiser, and Natasha Mesinkovska, for using cadavers to explore whether there is an equal number of hairs in each of a person's two nostrils."

This study was triggered by an interest in alopecia areata, a condition marked by hair loss on one's scalp, eyelashes, eyebrows, and nostrils. Pham et al. noted that many people who suffer from this condition are more prone to upper respiratory infections, allergies, and dryness because the condition also depletes the nose hair lining each nostril. And they realized that nobody had actually gotten around to counting the average number of nose hairs in humans, a first step in assessing what effects the lack thereof could have on patients' quality of life.

So that's what they did, using 20 cadavers (10 male and 10 female) from the medical school at the University of California, Irvine. Not only were the hairs counted in each nostril, but they used a measuring tape to determine the distance of hair growth at the upper, lateral, and lower nostril. The results: The average nose hair count per nostril is between 120 and 122 hairs, and nose hairs typically grow over a range of 0.81 to 1.035 centimeters. Trot out those statistics next time you're desperate to make small talk at a cocktail party.

Communication Prize

Citation: "María José Torres-Prioris, Diana López-Barroso, Estela Càmara, Sol Fittipaldi, Lucas Sedeño, Agustín Ibáñez, Marcelo Berthier, and Adolfo García, for studying the mental activities of people who are expert at speaking backward."

There's a group of residents of La Laguna, Spain, who are proficient in speaking backward (word inversion)—saying nasbue chesno instead of buenos noches, for example. Their efforts to have this unusual way of speaking recognized by UNESCO and the Canary Academy of Language have thus far not been successful, with the latter dismissing the phenomenon as having no scholarly value. Torres-Prioris et al. beg to differ. "Backward speech constitutes an extraordinary ability to quickly reverse words, pseudowords, and even sentences, which requires reordering phonemes while retaining their identity," they wrote in their winning 2020 paper. And they thought it provided a novel opportunity to learn more about how the brain processes phoneme sequencing.

The team recruited two male expert backward speakers for their experiments—both native Spanish speakers since Spanish is especially well-suited, as the phonemes always retain the same sound regardless of their position and surrounding segments. They also recruited a control group of 18 other men for comparison. All participants were subjected to general cognitive and memory tasks, as well as backward and forward language tasks. The two backward speakers also had their brains fully scanned for structural images, and those results were compared to a separate control group of 24 men.

Both backward speakers—who developed their ability naturally, with no explicit training—showed a clear behavioral advantage for reversing words, and this was not linked to their memory skills. The brain imaging for those two men showed increased gray matter volume and enhanced functional connectivity (white matter) in key parts of the brain associated with language. It's a tiny sample size, but the findings are consistent with earlier studies of expert simultaneous interpreters, suggesting that "language-related neuroplastic adaptations may emerge even from unconventional forms of language expertise, even those that are not publicly used in daily life or honed through professional training," Torres-Prioris et al. concluded.

Public Health Prize

Citation: "Seung-min Park, for inventing the Stanford Toilet, a device that uses a variety of technologies—including a urinalysis dipstick test strip, a computer vision system for defecation analysis, an anal-print sensor paired with an identification camera, and a telecommunications link—to monitor and quickly analyze the substances that humans excrete."

Schematic of a mountable toilet system for analyzing human excreta.

S. Park et al., 2020

Tired of constantly taking nasal swabs to test for COVID? How about installing a "smart toilet" that can track your health by regularly monitoring your urine streams and bowel movements, even testing for COVID (among other medical conditions)? That might be in our near future if Park has his way as inventor of the "PH Toilet for proactive healthcare." It's a smart toilet with integrated sensors capable of monitoring heart health, blood pressure, and oxygenation, as well as urine and stool samples.

There would be built-in urinalysis strips, and computer vision would function as a uroflowmeter, for instance, while deep learning would handle the stool classification. The prototype is designed for the male urine stream, but Park claims that one could add an extendable wand holding a urinalysis strip for women—or one could employ "sonouroflowmetry," analyzing the urine streams by sound. The COVID-specific version would feature a mountable attachment akin to a bidet, with modules to collect fecal samples and conduct rapid tests for the virus. Test results could be reported in minutes to the user's smartphone as well as to an anonymized tracing system using existing tracing networks. The same approach could also test for norovirus or the bacteria (like Shigella) that cause gastroenteritis, helping to control outbreaks in real time, according to Park.

It should be noted that the basic concept of a smart toilet has been around since the 1970s, and development has been slow because of privacy concerns. In addition to collecting sensitive medical information regarding one's urine and feces, Park's concept would identify each user via biometrics, namely a fingerprint and, um, the "anoderm" (skin of the anus). Yes, I am very excited about the possibility of a built-in toilet-cam taking pictures of my anus—just to ensure it's me (wink, wink). We are assured that all this sensitive data would be stored and analyzed in an encrypted cloud server, but still... we all watched Ingrid (Allegra Edwards) arguing with her indiscreet smart toilet on Upload ("Ingrid has a yeast infection). Suddenly, those nasal swabs seem far less invasive, don't they?

Nutrition Prize

Citation: "Homei Miyashita and Hiromi Nakamura, for experiments to determine how electrified chopsticks and drinking straws can change the taste of food."

Our sense of taste is pretty essential, not just for the enjoyment of our favorite foods and beverages but also to help us avoid foods that have gone bad or might otherwise be inedible. In their 2011 paper, Miyashita and Nakamura bemoan the fact we only have taste buds on our tongue, whereas the catfish has taste buds all over the surface of its body, making it a "swimming tongue." Their solution: augmenting our sense of taste with electric stimulation, producing a sour or metallic "electric taste" first noted back in 1752. (It even triggered the invention of the battery cell by Alessandro Volta.) Prior research has shown that one can alter perceived taste using electric stimulation, per the authors.

Miyashita and Nakamura inserted negative and positive electrodes into two different straws and then inserted each straw into one of two cups filled with a beverage containing an electrolyte. When the user drinks, they complete the circuit, and the straw delivers an electrical stimulus to the mouth to produce the "electric taste." They did the same thing for foods, inserting positive and negative electrodes and using chopsticks as the user interface instead of straws. Apparently, the ability to perceive this electric taste depends on voltage, so the authors added a voltage-adjustment function. "The goal of our system is to obtain a new layer of tongue that can detect tastes that we could not perceive previously," they concluded.

Education Prize

Citation: "Katy Tam, Cyanea Poon, Victoria Hui, Wijnand van Tilburg, Christy Wong, Vivian Kwong, Gigi Yuen, and Christian Chan, for methodically studying the boredom of teachers and students."

Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986) provided an iconic image of student boredom in the classroom.

YouTube/Paramount Pictures

Students being bored in class—as evidenced by nodding off, staring out the window, or doodling in their notebooks—is "ubiquitous," according to Tam et al., and that doesn't bode well for education since bored students could exhibit less motivation and lower academic achievement. But teachers can get bored, too, especially if they've been teaching the same material to apathetic students year after year.

In a 2020 study, Tam et al. investigated how a teacher's boredom might influence how bored students become in class and the resulting impact on their motivation to learn. A total of 437 students and 17 of their teachers from two local secondary schools in Hong Kong were asked to keep a diary for two weeks, recording their degree of boredom; students were also asked to rate how bored they perceived the teachers to be and how motivated they felt each day in class. The researchers found that, indeed, when a teacher was bored, students were less motivated to learn. And even though students' perception of when teachers were bored was inaccurate, their perceptions also resulted in lower motivation. Boredom begets boredom, no matter if it's real or perceived.

Tam et al. followed up with a 2023 paper detailing subsequent research to determine if the mere anticipation that a lecture or class will be boring becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. The first such study concerned a lecture as part of an undergraduate psychology course at King's College London and confirmed that the more students expected the lecture to be boring, the more bored they subsequently felt. The second involved a similar lecture at the University of Hong Kong, in which the researchers also attempted to manipulate students' expectations—an attempt that failed, although the results were otherwise in keeping with the first study. The third and final study (also at the University of Hong Kong) was more successful at manipulating expectations and once again confirmed the hypothesis. If you expect a lecture is going to be boring, you are probably going to feel bored.

Psychology Prize

Citation: "Stanley Milgram, Leonard Bickman, and Lawrence Berkowitz for experiments on a city street to see how many passersby stop to look upward when they see strangers looking upward."

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram is best known for his work on six degrees of separation (the small-world experiment) and his infamous 1963 study on obedience to authority, in which one group of participants was ordered to administer increasingly higher electric shocks to a second group of participants. The result was indeed shocking: 65 percent of those administering the shocks kept following orders up to the highest levels allowed for the experiment, despite expressing reluctance as the voltages increased. But Milgram also conducted a less controversial 1969 study on crowd formation, specifically examining the drawing power of crowds of different sizes. And he used a 50-foot stretch of a busy New York City sidewalk for his laboratory.

When a signal was given from the sixth-floor window of an office building across the street, a designated "stimulus" crowd (of either 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, or 15 people) would enter the observation area, stop, look up at the window for one full minute, and then were given a signal to disperse. The experiment was repeated several times and filmed for later analysis to see how many of the 1,425 pedestrians passing by altered their behavior in response, either by stopping and looking up or looking up without breaking stride.

The results: The size of the stimulus crowd was a key factor in how many passersby stopped. If just one person was looking up, a mere 4 percent of passersby would stop and also look up, compared to 40 percent who stopped when the stimulus crowd had 15 people. The same was true for passersby who looked up without stopping: 42 percent would look up if there was one person in the stimulus crowd, compared to 86 percent when there were 15 people in the crowd. That's contrary to an existing model assuming that the number of people available to join a group (the pedestrians in this case) would be the critical factor, not the size of the stimulus crowd.

Milgram and his co-authors emphasized, however, that the nature of the stimulus—what the stimulus crowd was looking at—also has an effect on those numbers. Their experimental scene wasn't especially interesting and hence didn't have much holding power; the passersby soon went on their way. But had there been, say, an acrobat performing on the ledge, it likely would have held their interest longer, causing the crowd to swell quickly before reaching a maximal size.

Physics prize

Citation: "Bieito Fernández Castro, Marian Peña, Enrique Nogueira, Miguel Gilcoto, Esperanza Broullón, Antonio Comesaña, Damien Bouffard, Alberto C. Naveira Garabato, and Beatriz Mouriño-Carballido, for measuring the extent to which ocean-water mixing is affected by the sexual activity of anchovies."

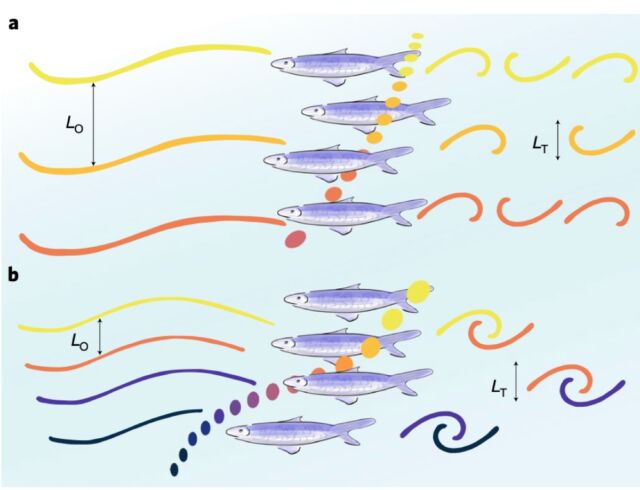

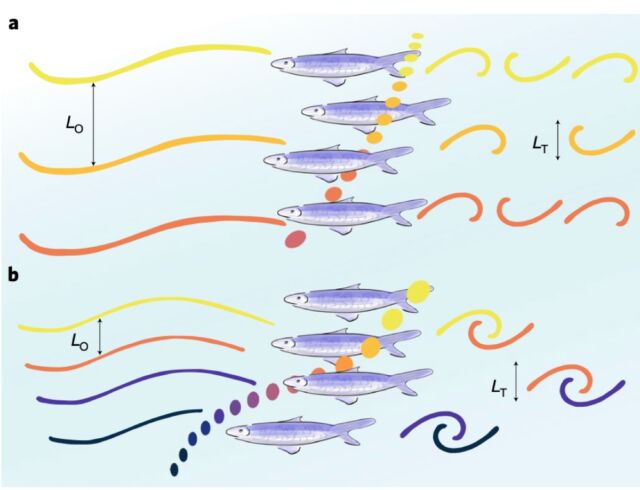

Schematic representation of biophysical turbulence caused by the sexual activity of anchovies.

B. Fernandez Castro et al., 2022

Ocean mixing is a critical area of research for climate science since it plays such a pivotal role in influencing the climate, affecting such water properties as temperature, salt, gas, and nutrients. Winds and tides are the major energy sources for ocean mixing on a global scale, but some scientists have suggested that certain swimming organisms—zooplankton, fish, or marine mammals—might also be a significant energy source for mixing on a more regional scale. But this type of biophysical turbulence is quite difficult to capture in lakes and oceans, and prior studies suggested the mixing efficiency of that activity would be too low to be significant.

Fernández Castro et al. contest that biomixing can serve as a highly effective ocean mixing agent, as demonstrated by their 2022 study analyzing data collected over two weeks in the summer of 2018, which revealed "intense biophysical turbulence" at night. The culprit: spawning anchovies. While the team didn't directly detect the presence of the fish, acoustic backscatter data was consistent with fish aggregations, and the plankton net hauls every morning had high concentrations of anchovy eggs. Those eggs were between four and 14 hours old, based on their stage of development, compared to fresher eggs gathered at night that were less than four hours old. So the spawning anchovies were clearly quite active at night. Their results provide "compelling evidence that fish can generate intense turbulence over prolonged periods," the authors concluded.

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.