Solid-state batteries have been hailed as the Holy Grail for electric vehicles. While that might be an overstatement, they do promise to boost range and slash charging times, bringing zero-emissions vehicles that much closer to parity with their fossil fuel competition.

Yet solid-state batteries, which use a solid electrolyte as opposed to a liquid or gel, remain just over the horizon. Recently, they’ve started to look less like vaporware and more like a real product, and they will probably make their way into cars and trucks by the end of the decade. Still, that’s a timeline that gives competitors an opening.

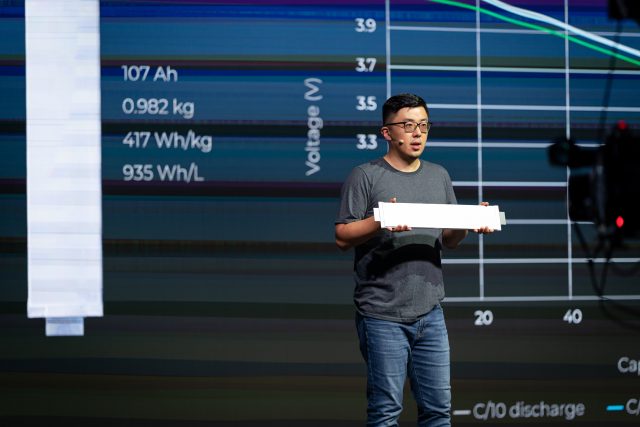

One of those competitors is a company called SES, which last week announced a new battery that promises to nearly double the energy density of today’s lithium-ion cells. The key was eliminating a piece of the battery that added weight and thickness—but to do so without introducing dangerous conditions that could lead to a fire.

SES eliminated graphite from the anode, which is the part of the battery that accepts lithium ions during charging. Instead, the new battery has a pure metal lithium anode. By dropping graphite from the anode, SES saved on weight and space, but it also had to figure out how to manage pure lithium, a highly reactive metal. When used as an anode, pure lithium often led batteries to premature deaths.

To make lithium-metal anodes safe and long-lived, the company managed the formation of dendrites using a three-prong approach. Dendrites are spiky structures that can form within lithium-ion batteries, particularly when the cells are charged or discharged quickly. If they grow too large, they can bridge the gap between the anode and cathode, causing a short circuit that can light the electrolyte on fire (many of today’s electrolytes are highly flammable).

Other companies are trying to eliminate the dendrite problem by replacing the liquid electrolyte with a solid one, creating a physical barrier to prevent the growth of dendrites. But mass producing lithium-metal batteries with solid electrolytes has been challenging, and perfecting the process will take several more years, which is why other companies have been researching hybrid approaches.

Salty solution

SES’s hybrid approach begins by coating the anode with a proprietary compound that allows the company to use pure lithium instead of graphite, which most of today’s lithium-ion batteries use. Then SES uses a liquid electrolyte saturated with a salt that CEO Qichao Hu told Ars is much safer to use.

“It’s actually mostly salt,” Hu said. “This new liquid is essentially very stable on lithium metal, very safe, nonflammable, non-volatile, non-organic.” A third-party evaluator was able to put a nail through a cell without causing a fire, something that you can’t do with today’s lithium-ion batteries.

The company monitors its batteries with artificial intelligence models trained on data gleaned from previous cells, looking for defects or variations that may eventually lead to problems. Right now, all this is happening in the lab, but SES is investigating ways to bring the same monitoring capabilities to vehicles on the road. Such a system might rely on basic parameters like temperature or voltage, or it may require additional sensors, Hu said. “All those are still in negotiation” with automakers, he added.

Should the sensors determine that a cell is not behaving properly, Hu said there are two possible ways to fix the problem. One might be to use a special charging protocol to replate the lithium on the anode, essentially attempting to undo the dendrite. But if that fails, or if special charging protocols aren’t available because a charger doesn’t support them, the battery pack could report a predicted cell failure so that the cell can be replaced before it causes a short.

Tight timeline

Tests of the new SES cells have been going well enough that automakers have been evaluating initial samples, and Hu hopes the company will have optimized samples by the end of next year. Currently, SES is partnering with GM, Hyundai, Geely, SAIC, and Foxconn, and it’s building a factory in Shanghai that’s scheduled to be finished in 2023.

“We’re targeting putting this in a car on the road, maybe 2025,” Hu said. Though years away, this would still put them ahead of solid-state competitors like Solid Power, whose realistic timeline targets the latter half of the decade. “Yes, it is tight,” he said. Hu said that the company’s work so far “gives us confidence that it’s doable. Aggressive, but doable.”

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.