An airborne lidar survey recently revealed the long-hidden ruins of 11 pre-Columbian Indigenous towns in what is now northern Bolivia. The survey also revealed previously unseen details of defensive walls and complex ceremonial buildings at 17 other settlements in the area, built by a culture about which archaeologists still know very little: the Casarabe.

In the last few years, lidar—which uses infrared beams to see what lies beneath dense foliage—has helped archaeologists map a long-hidden, long-forgotten landscape of towns, fortresses, causeways, canals, terraced fields, and ceremonial sites left behind by the Maya and Olmec civilizations across a huge swath of modern Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico. Those cultures are fairly well-known to archaeologists and historians, but lidar surveys have still revealed some huge surprises. And we know far less about the Casarabe culture, as it hasn’t been the subject of as many surveys and excavations as bigger, more famous civilizations like the Maya.

But a recent lidar survey, led by Heiko Prümers of the German Archaeological Institute, shed more light (infrared, specifically) on the Casarabe culture’s network of towns and cities, linked by hundreds of kilometers of causeways and canals. The survey also revealed a thriving urban culture in an area where historians once assumed very few people lived before Spanish colonization.

A nearly forgotten culture

Previous surveys in the Llanos de Mojos, a region of northern Bolivia, had spotted the ruins of several hundred pre-Columbian monuments scattered across about 4,500 square kilometers of the plains—an area centered on the modern Bolivian town of Casarabe. Archaeologists don’t know what the people who built those earthen mounds and pyramids called themselves, so they called the culture Casarabe, after the nearby town.

Based on radiocarbon dating at a few sites, we know that the Casarabe culture had taken off by around 500 CE. And we know that by the time Europeans arrived more than a thousand years later, the Casarabe were part of a diverse patchwork of ethnic groups who lived on the Llanos de Mojos. Many of those groups spoke different languages, and modern linguists say that’s probably because some of the groups in the Llanos had lived there for a very long time (the oldest sites on the plains date to at least 8000 BCE). Sometime in the past, other groups had moved south from what’s now Brazil; those groups brought Arawak languages and cassava farming with them. Still, other groups may have arrived just a few generations before the Spaniards.

Most of those different ethnic groups had some basic things in common, despite their differences in language: They farmed for a living (mostly maize and cassava), and they transformed the often swampy, flood-prone Llanos with earthen causeways, canals, and “forest islands” that rose above the surrounding wetlands. They built huge ceremonial mounds in a variety of shapes, and they surrounded their communities with fortifications of wooden palisades, earthen banks, and moats.

The Casarabe people lived in what’s probably the best farming land on the Llanos because it’s better drained and has generally more fertile soil than other areas of the plains. And there, they built a complex network of cities and towns linked by nearly a thousand kilometers of causeways and canals. Prümers’ recent survey uncovered the fortifications and the ceremonial districts of the Casarabe’s two largest cities, and it also revealed 11 smaller communities with ruins that have been hidden beneath foliage for centuries.

A tale of two cities

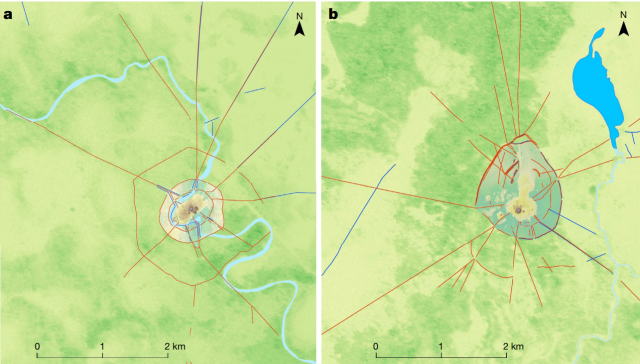

At the heart of the Casarabe’s landscape are two fortified cities, each with its own network of smaller communities spanning hundreds of square kilometers of the Llanos. Today, archaeologists know the cities as Landivar and Cotoca.

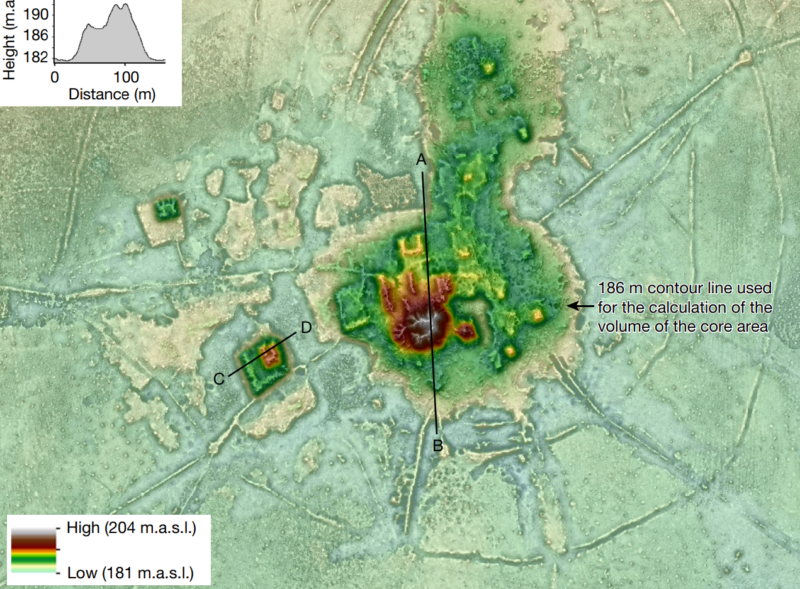

“These two large settlement sites were already known, but their massive size and architectural elaboration became apparent only through the lidar survey,” wrote Prümers and his colleagues in their recent paper. Landivar, it turns out, encompassed 315 hectares within its three sets of moats and ramparts (that’s just slightly smaller than Central Park). Cotoca’s three-layered defenses protected a smaller area: 147 hectares (that’s just slightly larger than the National Mall).

And the Casarabe were apparently serious about their security; the authors noticed raised platforms at "strategic points" along the causeways and at the entrances to each city. “Access to these large settlement sites may have been restricted and controlled,” wrote Prümers and his colleagues.

Both cities had a central district that boasted big, imposing structures. The 22 hectares of Cotoca’s urban core are built up six meters higher than the rest of the city atop a massive earthen terrace, and it features towering 22-meter-tall conical pyramids, as well as rectangular and U-shaped platforms. This terraced district was probably the ceremonial and political center of the city.

All roads lead to... Cotoca?

From each city, earthen causeways radiate out like spokes, connecting the city with surrounding towns and villages even during the rainy season, when the Llanos might be flooded or a swampy mess. Casarabe towns had just a single layer of defensive ramparts that enclosed an area about the size of Cotoca’s central terrace; each town had its own smaller terrace with a few earthen platforms on top. Even smaller towns—about 2.5 hectares or so—had only a circular ditch for protection and a small central platform.

The hierarchy is clear, even from the air 1,500 years later; causeways linked the cities to the towns and the towns to the villages but didn’t link the smaller communities to each other. All roads led to the city. If you wanted to travel between lesser places, you were on your own.

Each city was apparently the hub of its own network of communities; archaeologists haven’t found any causeways linking Cotoca to Landivar. Some of the larger towns also appear to have been the centers of their own clusters of smaller communities. This suggests that instead of a big, centrally organized state like the Inca in Peru, the Casarabe culture may have been a group of independent city-states that happened to share a culture and an architectural style. But we don’t really know, and we probably won’t find out without a lot of digging.

Nature, 2022 DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04780-4 (About DOIs).

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.