Plumbonacrite has previously been found in later works by Rembrandt.

When Leonardo da Vinci was creating his masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, he may have experimented with lead oxide in his base layer, resulting in trace amounts of a compound called plumbonacrite. It forms when lead oxides combine with oil, a common mixture to help paint dry, used by later artists like Rembrandt. But the presence of plumbonacrite in the Mona Lisa is the first time the compound has been detected in an Italian Renaissance painting, suggesting that da Vinci could have pioneered this technique, according to the authors of a recent paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Fewer than 20 of da Vinci's paintings have survived, and the Mona Lisa is by far the most famous, inspiring a 1950s hit song by Nat King Cole and featuring prominently in last year's Glass Onion: a Knives Out Mystery, among other pop culture mentions. The painting is in remarkably good condition given its age, but art conservationists and da Vinci scholars alike are eager to learn as much as possible about the materials the Renaissance master used to create his works.

There have been some recent scientific investigations of da Vinci's works, which revealed that he varied the materials used for his paintings, especially concerning the ground layers applied between the wooden panel surface and the subsequent paint layers. For instance, for his Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1503–1519), he used a typical Italian Renaissance gesso for the ground layer, followed by a lead white priming layer. But for La Belle Ferronniere (c. 1495–1497), da Vinci used an oil-based ground layer made of white and red lead.

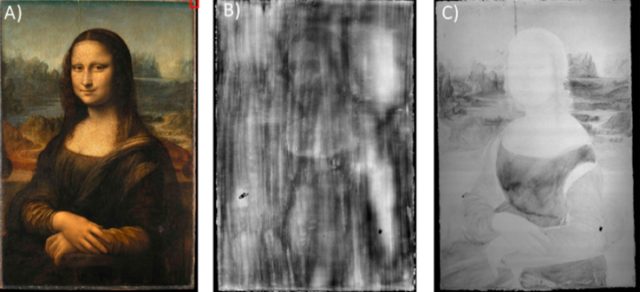

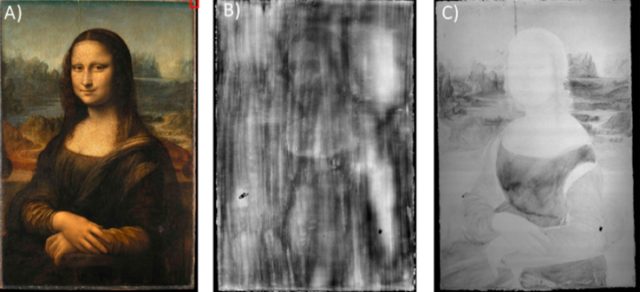

For his large wall painting, The Last Supper—his second most famous work—he used an oil-based lead white priming layer rather than the traditional fresco technique. As for the Mona Lisa, various X-ray analyses of the painting showed the presence of heavy elements within the poplar wood panel, which could mean that da Vinci used a lead-based pigment or an oil medium treated with lead during the grinding. The ground layer appears to be a single layer of lead white with no gesso.

(a) The Mona Lisa. (b) X-ray radiography revealing a radio-opaque, thick absorbing paint layer

under the painting surface. Copyright E. Ravaud. (c) Pb-Lα MA-XRF map.

V. Gonzalez et al., 2023

In other words, da Vinci was constantly experimenting with his artistic materials. "From 1485 to 1490, each known easel painting of Leonardo presents a different type of ground layer," Victor Gonzalez of Universite Paris-Salcay and his co-authors wrote in their paper. "Their only common features are that they are oil-based and that they contain the lead white pigment called biacca by Leonardo in his writings."

Gonzalez et al. decided to take a closer look at the Mona Lisa's ground layer with X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy, analyzing a tiny microsample taken from a hidden corner of the painting back in 2007. They were surprised to find plumbonacrite in the mix in addition to lead white and oil since the compound has previously been detected only in later paintings. These include a painting fragment by Vincent van Gogh—likely due to the degradation of a red lead pigment as a result of exposure to light—and in the thick lead white impasto used by Rembrandt in several of his paintings, most notably The Night Watch.

Also, like Rembrandt's impasto, Mona Lisa's ground layer has a low level of cerussite, which is not present in either the Virgin and Child with St. Anne or Belle Ferroniere. The authors view this as evidence of a possible common signature of the processes both artists used.

The authors hypothesized that da Vinci might have used plumbonacrite as the ground layer for the Mona Lisa and turned to his writings to see if they could find any mention of terms that might relate to lead oxide—specifically litharge (an orange-red form stable at room temperature) and massicot (a yellow form stable at higher temperatures). For the first, the most relevant mention was found in the Codex Ardundel as letargiro di pionbo, part of a recipe for a remedy to treat skin and hair. (People were unaware of the compound's toxicity at the time.) Their findings for massicot were less conclusive. Several French and English translations mention "macicot" or "masticot," but da Vinci used the word gialorino, which could refer to a lead-tin yellow pigment rather than lead oxide.

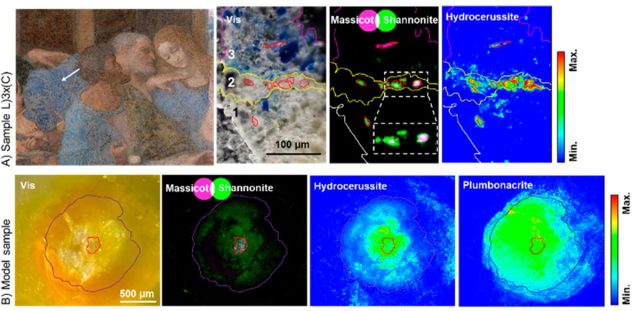

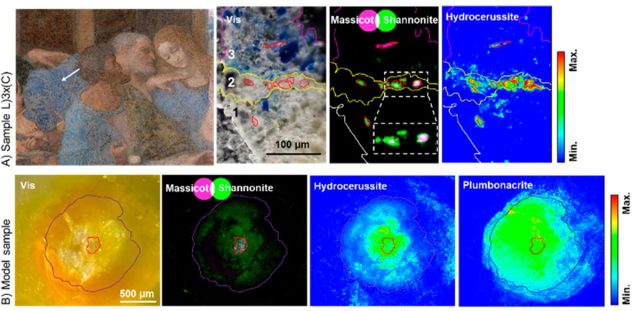

Visible OM images and SR-μ-XRPD maps of samples from The Last Supper.

V. Gonzalez et al., 2023

Gonzalez et al. next conducted similar analyses on 17 microsamples from da Vinci's The Last Supper. This revealed three types of layers: a translucent white ground layer, an opaque white priming layer, and at least one colored layer. They also found plumbonacrite grains in the priming layer of 12 of the 17 samples, in both litharge and massicot forms, as well as throughout the colored paint layers. They also detected a lead oxycarbonate called shannonite surrounding the plumbonacrite crystals in the priming layer—the first time shannonite has been detected in a historical painting, according to the authors.

Because plumbonacrite is only stable under alkaline conditions, the authors concluded that da Vinci did not include the compound in his mixtures for the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper as a primary goal. Rather, it was likely "a simple consequence of the strong alkalinity of the medium," they wrote, adding that it may have been a means of getting the paints to dry more quickly, although there is no hard evidence in da Vinci's recipes.

“We have long known that Leonardo was an inveterate experimenter,” William Wallace of Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study, told CNN. “Therefore, it is not all surprising that we see him experimenting in other media, especially given his dedicated search for the best painterly techniques (often untraditional) to create his ‘living’ works of art.”

The authors next plan to experiment on model paints to take a closer look at the interactions between the oil medium, lead oxide, and the lead white pigment, hoping to identify the chemical reaction pathways likely to yield unusual lead-based mineral phases like plumbonacrite.

Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2023. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.3c07000 (About DOIs).

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.