Details of a potential US-Indian partnership in human spaceflight remain murky.

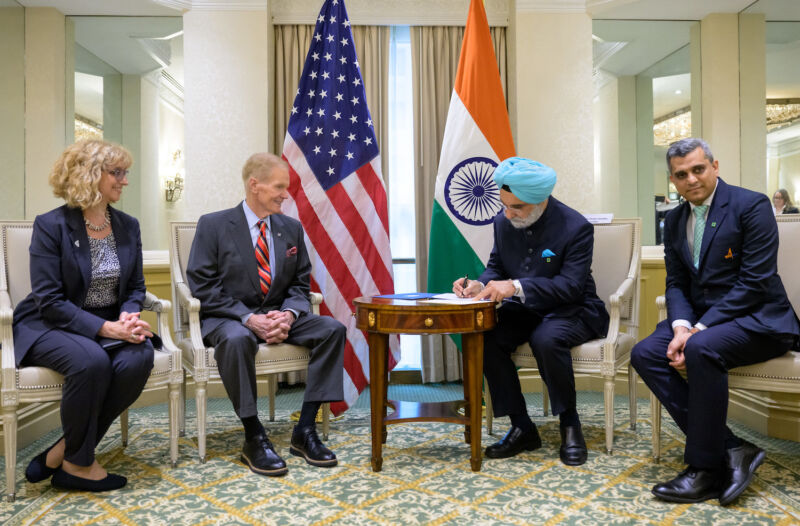

When India’s ambassador to the US signed up his country to the Artemis Accords last month, it signaled the world’s most populous country—with a growing prowess in spaceflight—could be turning toward the United States as a partner in space exploration.

India became the 27th country to sign the Artemis Accords, a non-binding set of principles among like-minded nations guiding a vision for peaceful and transparent exploration of space. The accords cover the international registration of human-made space objects, the open release of scientific data, and an agreement for nations not to claim territory on the Moon or other planetary bodies, among other tenets.

The Artemis Accords started under the Trump administration, an effort spearheaded by former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and Mike Gold, an attorney and longtime space industry official. Bill Nelson, the NASA chief under President Biden, has embraced the accords. He said the principles are “just common sense.”

“You come to somebody’s aid in distress … You try to have commonality of parts, you respect each other’s territory,” Nelson said.

Details about future cooperation between the US and India remain scarce. Nelson plans to travel to India later this year for meetings and discussions with Indian space officials. One objective of Nelson’s trip will be to hammer out broad objectives for a “strategic framework” for human spaceflight cooperation.

Despite the name of the Artemis Accords, there’s no guarantee that India will play a significant role in NASA’s Artemis program to return astronauts to the Moon and eventually send humans to Mars.

“There’s no implication of a signatory to the Artemis accords also being part of the Artemis program,” Nelson told Ars.

But none of the other 26 signatories to the Artemis Accords—a list that includes European space powers and Japan—has their own human spaceflight program. India is developing a human-rated spacecraft called Gaganyaan that could be ready to fly people into low-Earth orbit in 2025, several years later than originally planned.

Visitors look at an actual scale model of India's Gaganyaan Orbital Module, a human-rated

spacecraft now in development, at the Human Space Flight Expo in 2022.

MANJUNATH KIRAN/AFP via Getty Images

“The fact that they are a nation that intends in the future to fly own their own astronauts, is that significant? The answer is yes,” Nelson said. “I think it’s of significance that a major country that’s not considered aligned with the US (is) a signatory.”

“I’ve described India as a sleeping giant and one that is quickly awakening," Gold told Ars. "India is absolutely vital to global space development, and Artemis in particular, since the country is active with lunar programs, Martian programs, and now even human spaceflight.”

Through the Artemis program, NASA hopes to land astronauts on the lunar surface later this decade for the first time since 1972. NASA officially targets the end of 2025 for the first Artemis crew landing on the Moon, but the schedule is almost certain to slip as new spacesuits from Axiom Space and a new human-rated lunar lander from SpaceX proceed through development and testing.

What's next?

Where India might fit into the Artemis program is still to be determined. But India has launched as many space missions this year as Japan and Europe combined, with another milestone launch scheduled later this month with a robotic spacecraft that will mark India's second attempt to achieve a controlled landing on the Moon, following a landing failure in 2019.

India successfully sent a spacecraft to Mars a decade ago, and international satellite operators regularly rely on Indian rockets to put their missions into orbit.

"They come to Artemis with activities that are already directly relevant to the program," Gold said of India. "Neither the United States nor India needs to alter their trajectories at all. Their activities are already highly complementary."

Before the Artemis Accords signing, the Indian Space Research Organizations—India's space agency—and NASA were already working together on a sophisticated radar Earth observation satellite called NISAR scheduled for launch in 2024. An Indian satellite launched on the space shuttle in the 1980s.

But ISRO and NASA have not worked together in any significant way in the realm of human spaceflight or space exploration.

An Indian astronaut could fly to the International Space Station next year under an agreement with NASA.

NASA

The partnership between the US and India in space could take a step forward next year with the flight of an Indian astronaut to the International Space Station. NASA has agreed to provide advanced training to Indian astronauts at the Johnson Space Center in Houston before a flight opportunity to the space station in low-Earth orbit. The Indian astronaut, still unnamed, would likely fly on a short-duration mission to the ISS, according to Nelson.

Only one Indian citizen has flown to space before. Rakesh Sharma, a pilot in the Indian Air Force, launched to the Soviet Union's Salyut space station for a nearly eight-day mission in 1984.

India's space program has held closer ties with Russia in the past. Russia provided upper-stage engines for India's GSLV Mk.II rocket until India developed its own engine for the job. And four Indian astronauts slated for the Gaganyaan program completed more than a year of training at Russia's Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center near Moscow in 2021, according to Indian media.

Despite India's overture toward a closer relationship with NASA, the Asian power remains linked with Russia. India still imports significant amounts of Russian oil and has not officially condemned Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

But Russia's space program is not the force it once was. China is now the rival space power for the United States.

Chinese space officials said in May they plan to land a crew on the Moon by 2030, a precursor to longer-term ambitions to develop a lunar research station in partnership with Russia, which has indicated it will not join the Artemis Accords or the US-led Artemis program. China says it is recruiting other countries to its own Moon exploration effort.

Like China, NASA wants to expand its roster of partners beyond traditional collaborators. Alongside European countries, Japan, and Canada, the Artemis Accords signatories include Brazil, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates. Ecuador signed the Artemis Accords on the same day as India.

Ultimately, if enough countries throw their weight behind the Artemis Accords, space policy experts hope the agreement will foster an environment the principles outlined in the accords become "norms of behavior" in space. India, with its burgeoning space program and a population of 1.4 billion, carries a lot of weight.

“While it may be unlikely for China and Russia to sign, the accords were designed to influence those countries by creating precedent," said Gold, now an executive at the space company Redwire. "The precedent of the accords will have impact on the nations that don’t sign, and that precedent will be more powerful with India joining."

Smooth sailing not guaranteed

As NASA has discovered with Russia, cooperation between nations in spaceflight sometimes comes with diplomatic hurdles.

India shot down one of its own satellites in a 2019 test of an anti-satellite weapon that the country's prime minister, Narendra Modi, declared a "moment of pride" for the Indian people that would catapult the country into an echelon of global space powers. At the time, then-NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine called the anti-satellite test a "terrible thing" that was "not compatible with the future of human spaceflight."

The high-speed collision between an Indian missile and its target satellite showered low-Earth orbit—including the region of space traversed by the ISS—with hundreds of debris fragments. Those shards of debris, which have now re-entered the atmosphere, could have endangered the space station or other satellites in orbit.

One of the principles of the Artemis Accords is an agreement among signatories to "preserve a safe and sustainable environment in space is critical for both public and private activities."

The United States has since pledged not to perform any more anti-satellite tests after already demonstrating its capability to shoot down satellites on multiple occasions. China and Russia have also demonstrated anti-satellite weapons.

"We don't do ASAT tests," Nelson said. "That's our position."

Gold said the thrust of the Artemis Accords is to establish norms of behavior for nations operating in deep space, such as near the Moon or Mars, and they don't necessarily cover what happens closer to Earth. "That's intentional because Earth orbit activities are already highly regulated, and there are established processes for that.”

Source

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.