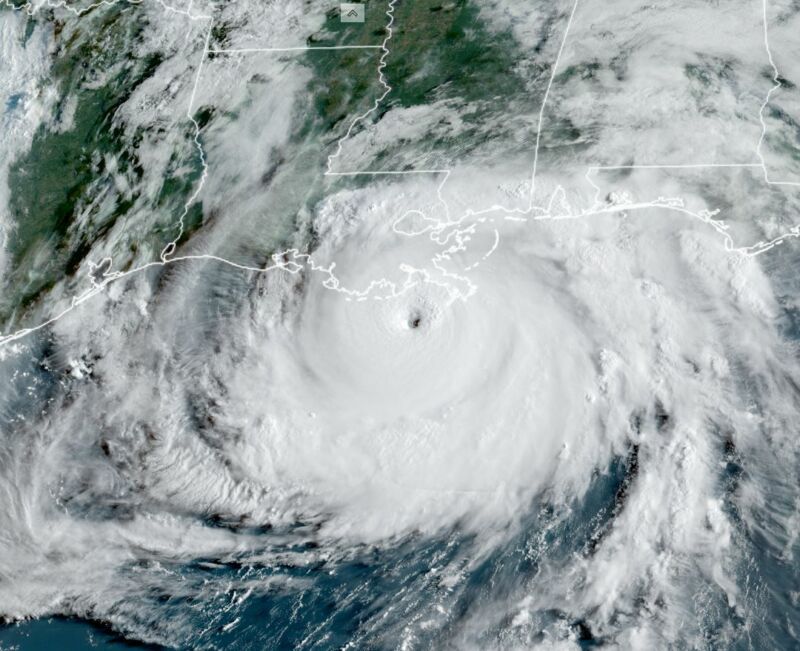

Hurricane Ida roared into the southern US state of Louisiana on Sunday at 11:55 am local time (16:55 UTC) with sustained winds of 150 mph. The storm's distinct eye moved into the state's southernmost seaport, Port Fourchon, setting about destroying buildings and scattering boats moored nearby.

But Ida did not stop there. Instead of weakening as it marched northward toward the larger cities of New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Ida appeared to maintain its organization with a distinct eye and even small vortices rotating around the center of the storm.

Ida brought many forms of devastation to Louisiana. Its storm surge swamped coastal areas and pushed water levels to flooding levels in Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans. Heavy rains flooded low-lying areas of the state.

But probably the most damaging aspect of the storm for most Louisianans came from the storm's winds—knocking trees into thousands of homes and knocking out power to more than 1 million customers. This affected about half the state's population and nearly all of the urban Baton Rouge and New Orleans areas and may cripple initial recovery efforts.

This is because Ida's winds kept howling. More than two hours after landfall, at 2 pm CT, Ida's winds were estimated to have fallen just 5 mph, to 145 mph. At 4 pm the storm's maximum winds were still a staggering 130 mph. At 10 pm, more than 10 hours after landfall, Ida still packed the punch of a Category 2 hurricane, with estimated winds of 105 mph.

This slow weakening is in stark contrast to a typical hurricane. Based upon a simple model for a landfalling hurricane, a storm like Ida would have been expected to drop from 150 to 100 mph after four hours, and to 70 mph after 10 hours. So why did Ida maintain its devastating intensity for so long?

Some of this is due to geography. The Louisiana coastland is largely made up of swampy, marshy land barely above sea level. Anyone who has ever driven Interstate 10 across Louisiana knows this. The lengthy Atchafalaya Basin Bridge between Lafayette and Baton Rouge traverses above seemingly endless swampy ground, and this region lies about 50 miles inland from the coast. As Ida approached Louisiana, its storm surge pushed warm water from the Gulf of Mexico inland. This allowed the storm to continue traversing "over water" even as it moved dozens of miles into the state.

Ida's slow weakening was also fueled by the "brown ocean effect," in which latent heat from very wet soils can mimic the moisture-rich environment of the ocean. The Southern Louisiana marshes are fertile environments for this kind of latent heating. Because of its relatively slow movement, less than 10 mph to the north, Ida spent several hours over the more moist environment.

Ida finally succumbed to drier ground overnight and has weakened into a tropical storm by Monday morning. It should rapidly weaken further as it travels over Mississippi today. Enough of a low pressure system may still remain by late Thursday, however, to allow the remnants of Ida to become an extratropical storm after it emerges into the Atlantic Ocean and rips off to the northeast. Good riddance.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69789950/latest.0.jpeg)

3175x175(CURRENT).thumb.jpg.b05acc060982b36f5891ba728e6d953c.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.