- Brigham researchers studying how and why certain cell types proliferate in the gut found that xanthine, which is found in coffee, tea and chocolate, may play a role in Th17 differentiation

- Insights may help investigators better understand gut health and the development of conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease

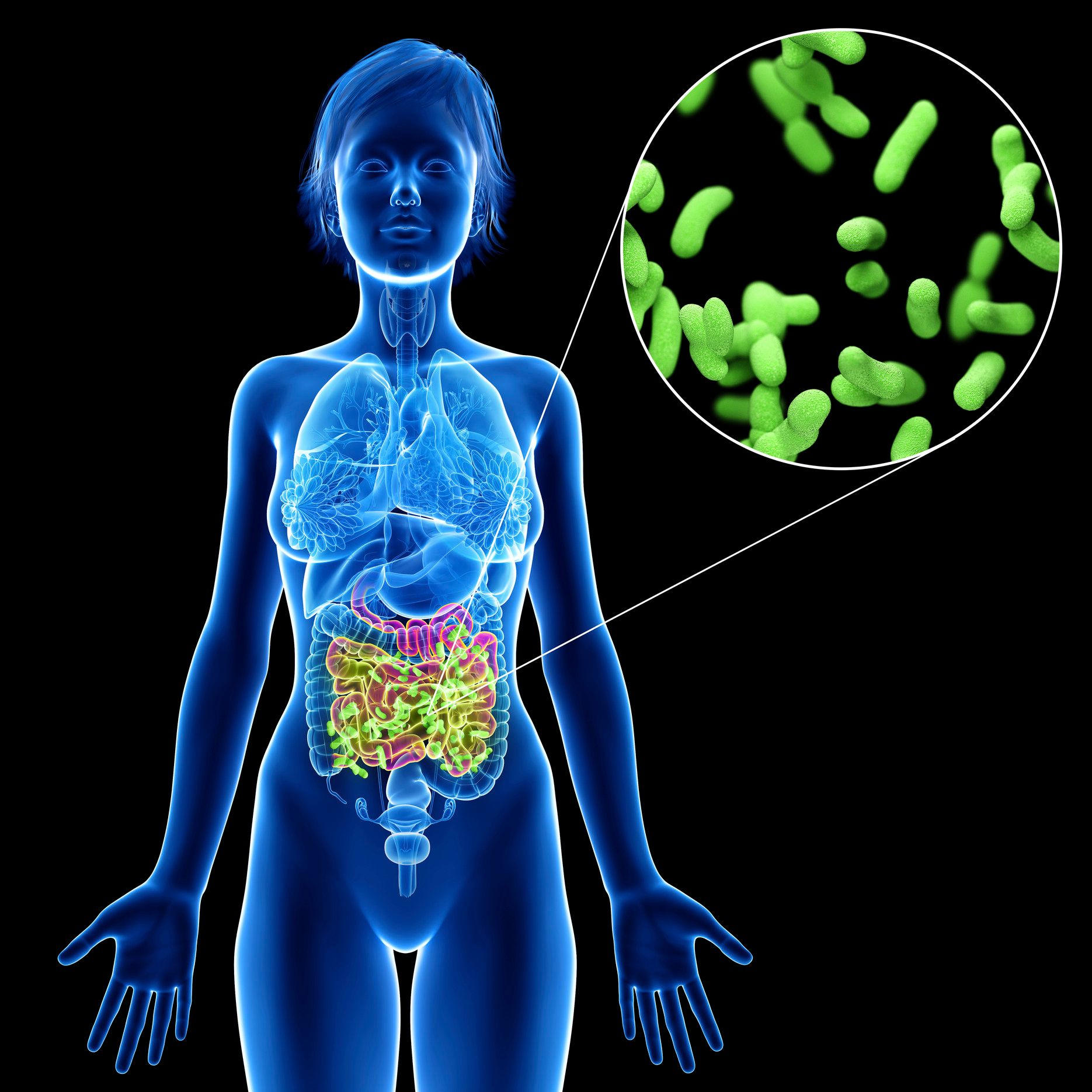

The human gut is inhabited by a diverse community of microbes that play a crucial role in both health and illness. Certain microorganisms are believed to be involved in the onset of inflammatory disorders, such as IBD, however, the exact process linking these microbes to the activation of the immune system and the eventual development of the disease is still not fully understood.

Researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, have conducted a new study to shed light on the factors that trigger the generation of Th17 cells in the intestine. Th17 cells are a crucial subtype of cells in the gut, and this study aims to uncover some of the previously overlooked molecular mechanisms and events that lead to their differentiation in the gut.

One of those players is the purine metabolite xanthine, which is found at high levels in caffeinated foods such as coffee, tea, and chocolate. The results of the study were recently published in the journal Immunity.

“One of the concepts in our field is that microbes are required for Th17 cell differentiation, but our study suggests that there may be exceptions,” said co-lead author Jinzhi Duan, Ph.D., of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endoscopy in the Department of Medicine at BWH. “We studied the underlying mechanisms of Th17 cell generation in the gut and found some surprising results that may help us to better understand how and why diseases like IBD may develop.”

While illuminating the steps leading to Th17 cell differentiation, the researchers unexpectedly discovered a role for xanthine in the gut.

“Sometimes in research, we make these serendipitous discoveries—it’s not necessarily something you sought out, but it’s an interesting finding that opens up further areas of inquiry,” said senior author Richard Blumberg, MD, of the Division of Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Endoscopy in the Department of Medicine. “It’s too soon to speculate on whether the amount of xanthine in a cup of coffee leads to helpful or harmful effects in a person’s gut, but it gives us interesting leads to follow up on as we pursue ways to generate a protective response and stronger barrier in the intestine.”

Interleukin-17-producing T helper (Th17) cells are thought to play a key role in the intestine. The cells can help to build a protective barrier in the gut, and when a bacterial or fungal infection occurs, these cells may release signals that cause the body to produce more Th17 cells. But the cells have also been implicated in diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and IBD.

Duan, co-lead author Juan Matute, MD, Blumberg, and colleagues used several mouse models to study the molecular events that lead to the development of Th17 cells. Surprisingly, they found that Th17 cells could proliferate even in germ-free mice or mice that had been given antibiotics wiping out bacteria. The team found that endoplasmic reticulum stress in intestinal epithelial cells drove Th17 cell differentiation through purine metabolites, such as xanthine, even in mice that did not carry microbes and with genetic signatures that suggested cells with protective properties.

The authors note that their study was limited to cells in the intestine—it’s possible that crosstalk between cells in the gut and other organs, such as the skin and lung, may have an important influence on outcomes. They also note that their study does not identify what causes Th17 cells to become pathogenic—that is, play a role in disease. They note that further exploration is needed, including studies that focus on human-IBD Th17 cells.

“While we don’t yet know what’s causing pathogenesis, the tools we have developed here may take us a step closer to understanding what causes disease and what could help resolve or prevent it,” said Blumberg.

- aum and Karlston

-

2

2

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.